Graham Reid | | 4 min read

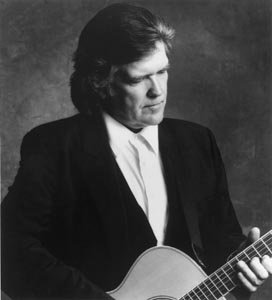

In a way it almost doesn’t matter if

you don’t know who Guy Clark is -- Bono and the rest of U2 do.

Not only do they attend his concerts (and a month ago, when Clark was in Dublin for a television show, they dropped by there too), but the Irish stadium rockers have signed this quiet singer/songwriter from Nashville to a distribution deal with their newly established Mother record label.

Lyle Lovett knows Clark as well. In

fact, Clark was instrumental in getting Lovett his record deal.

So even if you haven’t heard of him,

a whole heap of people from Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash and Rodney

Crowell (all of whom appear on his new Old Friends album) through to

Jerry Jeff Walker (who had a hit with Clark's L. A. Freeway) and

Johnny Cash (he picked up Texas 1947) - they all know of him.

Maybe it’s about time you tuned in?

Like Butch Hancock and Townes Van Zandt, Clark is an out-of-the-mainstream kind of

singer/songwriter almost too self-effacing for his own good.

Speaking from Sydney, Clark is as

economic in speech as he is in his lyrics.

Of his role in getting Lovett signed,

all he will say is: “I played his tapes for a lot of people and

finally found the right guy. I get a lot of tapes from people.”

When it comes to saying what he has

been up to in the last five years since his previous album, Better

Days, he plays it pretty close to the chest.

“I’ve been mostly just writing

songs and doin’ gigs. I play all I want to and I need a combination

of playing and writing. I don’t have any reason to write unless I’m

going to play -- and no reason to play unless I’ve written new

songs for the folks. I have a nice balance between the two.”

Clearly, Clark is not a man to waste

anybody’s time, and time spent with the Old Friends album is not

time wasted.

A collection of bare-to-the-bone song,

the album is sparely produced by Clark (who is also no slouch with

oil painting, if his cover art is any indication) and a deliberate

move away from a more full sound as on his earlier South Coast of

Texas.

“It’s hard to go back because what is, is what is,” he says about this change of style. “I would have liked to have made those earlier albums more sparse, more like this one. I like this sound better -- it also makes things more intense, and that’s the whole point.”

The songs are certainly that.

Immigrant Eyes is an immediate

stand-out as Clark reflects on the immigrants to America swarming

through Ellis Island. It also includes a killer of a line to pull the

listener up short just when it is sounding a little too romantic.

“The guy I wrote that with, Roger

Murrah, and I actually wrote it for a mutual friend as a gift. We all

have, maybe not grand-parents, but maybe

great-great-great-grandparents who were immigrants so that song is

true somewhere down the line.”

The truth has always been Clark's currency -- “I learned a long time ago you have to write about what you know, and those songs are the ones that ring truest, and truth is stranger than fiction” – and a strong autobiographical strain runs through his work.

Born in Texas 46 years ago, Clark spent

much of his childhood living with his grandmother in a seedy hotel in

Montana. It was when he moved to Houston, Texas to work in television

he met Jeff Walker and Townes Van Zandt.

By the early Seventies he was in

Austin, the hub of an alternative country sound, and although loath

to be described as a country singer, country musicians like Walker,

Ricky Scaggs and Johnny Cash have all covered his material And there

has been plenty to cover even though his album output stands at only

six.

As the Dallas Times Herald pointed all

out on the release of Better Days, “He doesn't write songs, he

writes standards”.

And Better Days was picked as the top

country album of 1983 by Britain's rock magazine NME.

Among the standout new songs on Old

Friends is a Joe Ely track, The Indian Cowboy, a curious narrative

which speaks of the fragile line between life and death but opens

with the lines, “If you ever go out to the circus, where the

Wallendas walk on the wire . . . .”

“Joe was one of few guys I know who

actually left home and join the circus,” says Clark. “He was a

stock-handler for the Ringling Brothers and Indian Cowboy was song he

put together about that.”

Despite the intensity of these new

songs and earlier material like his classic Randell Knife – a

narrative of a boy a his father and the ties that bind which he wrote

after the death of his father – Clark is by no means a down kind of

guy.

Texas Cooking, Homegrown Tomatoes, A

Nickel For the Fiddler and other earlier songs have a tail-kicking

cheerfulness that give the lie to the perception of him as a serious

and cheerless singer.

The new album even includes a track

called Heavy Metal, but it's about “dancing with the widow-maker”,

a “big ol' D-10 Caterpillar, 175,000 pounds of steel”.

“Everybody has had that experience of

something so powerful they become mesmerised by it and for some

reason mankind has always been fascinated by pushing dirt around,”

says Clark by way of explanation. “That song was an idea for some

existential statement on pushing dirt around.”

And then there is the final track on

the album, the wry Doctor God Doctor.

It tells of going to the doctor in a

state of complete emotional breakdown. And the doctor's advice?

“Quit whinin', straighten up and fly

right, life isn't a piece of cake . . .”

post a comment