Graham Reid | | 5 min read

David Thomas: Who is it?

Blame punk’s redrawing of the map -

or Yoko Ono, or the much more irritating Celine Dion if you will --

but the limits of our tolerance to the human voice have certainly

shifted over the past few decades.

We can now listen with impunity to

Natacha Atlas’ careening Arabic trip-hop as much as be in awe of

Whitney Houston’s lung capacity, or delight in the qawwali music of

the late Sufi master-singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

A couple of years ago I was impressed when

I saw Chris Knox front a band at the Laneway Festival in Auckland and

snarl and roar his way through a short but terrific set: Knox has had

a stroke and so cannot “speak”. But he sure could “sing” and

people loved it, not just for his courage. It actually made weird

sense from a man who always challenged preconceptions.

So with people like the Inuit artist

Tagaq ready to mess up our minds with their “singing”, when did

this shift in popular culture begin?

Bob Dylan has been one of the many who

have redefined the limits of the public, human voice. Hearing him

sawing away nasally allowed Jimi Hendrix the confidence to sing (and

he could) and set new, some would say lower, thresholds. Hence early

and whiny Neil Young.

And one need only think of Kate Bush’s

alarming arrival on the scene back in the late Seventies with the

octave-ignoring Wuthering Heights, the peculiar career of Leo Sayer,

or Johnny Rotten’s sneering delivery.

No-talent singers (recent Ringo)

are a different category, of course. And it’s immaterial that most

people in rock bands can’t “sing” in the traditional sense.

Indeed Jordan Luck of the Exponents once picked up an award for best

vocalist, much to his delight and amusement.

“But I can't sing,” he said.

Few complain when Marianne Faithfull,

Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen or Mark Knopfler take their “distinctive”

style to their own work, written within the limits of their range.

There have always been the oddities:

Tiny Tim’s worryingly high falsetto, Lee Marvin growling Wandering

Star from the basement of his belly, David Surkamp from Pavlov's Dog, Whatsisname from Supertramp and

that equally irritating bloke who sang with Yes . . .

The recent emergence of “world music"

may simply be ethno-tourism for some, but it has opened our ears to

the diversity of the human voice. And it’s diverse out there, all

right.

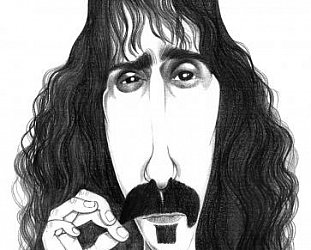

Today there are something like 150

Frank Zappa CDs released, the complete works of Yoko Ono (a box set

for Yoko? Who ever would have imagined), Mark E. Smith from the Fall

has built a career on very little, thank you, and Brian Johnson out

front of AC/DC shows no signs of slowing down.

It would seem anything is possible.

In a word, Bjork.

It’s entirely possible as many people

on the planet now accept the vocal gymnastics of Bjork as they do

Cher’s wall-shaking vibrato.

And in the late Nineties came the

rehabilitation of David Thomas – not a name remotely familiar in

the wider world.

But for those who do know, his sudden

appearance as the arresting frontman with Pere Ubu in the late

Seventies was earth-shattering enough.

If he had never done anything other

than declaimed and shouted the terrifying 30 Seconds Over Tokyo he’d

still be (almost) famous.

David Thomas was the oddest of vocalists; he

sounded like a turkey clearing its throat - or a man gargling Talking

Heads’ frontman David Byrne. His style was all quivering agitation

which gymnastically ignored an octave or two and ran the occasional

glottal Stop sign.

And then Thomas got really interesting.

When Pere Ubu, out of Cleveland, split up in the early-Eighties (later to reform, of course) he took off on an indescribably fascinating, challenging and demanding solo career singing what sound like demented fairytales and folksongs. He interspersed his albums with disarmingly strange spoken-word passages and generally delivered up noir-dance music for a particularly bad night in a roadhouse somewhere along the David Lynch highway.

His co-conspirators over the years have

been drummer Anton Fier - guiding figure behind the Golden Palominos

collective out of New York - and the acclaimed Anglo-folk guitarist

Richard Thompson, a man whose avant.-guitar skills find him cutting

like a blunt hacksaw blade through Thomas’ songs.

If there’s a connecting thread in

Thomas' oddball sounds it's in the Talking Heads-like percussive

quality and the same Tom Waitsean clank of barrel organ and monkey

down a dark alley.

There wouldn't seem to be a lot of call

for this music, but it’s one of those rare cases where the world

has caught up and David Thomas is suddenly somewhere nearer the

centre of the frame than he once was.

The five CD box set Monster – Thomas’

solo career between '81 and '87 – might be four and a half albums

more of Thomas than most people could take, but it is astonishing

stuff.

There are nightmarish visions, drifting

psychedelics, creaky accordion and trap drums, and a truly terrifying

live album where Thomas delivers up scary and strangely beautiful

versions of I Can't Help Falling in Love and the Beach Boys’ lovely

Surfer Girl.

It makes you reconsider the notion of

“singing”.

Whatever it is he’s doing (and it’s

probably not “singing" for most listeners), it communicates

powerfully, viscerally and with humour. This is the kind of box set

you extravagantly buy on spec, are briefly disappointed by, and then,

in giving it another go, find yourself mesmerised for months.

And after all that has preceded it –

from Tiny Tim and Bob Dylan to Yoko and Tagaq -- it also seems to make

sense.

It's that voice, Carruthers, that

voice. It haunts me still.

Anxious music for an anxious time,

perhaps?

post a comment