Graham Reid | | 18 min read

My collection of schoolboy poetry which I would agonise over late at night, laboriously using my Scripto fountain pen and Radiant Blue ink, has long since vanished. Thank God. I’m sure it was full of adolescent anxieties -- one “poem” was about Oedipus, about whom I knew nothing other than I liked the name.

But one piece remains with me in the memory.

It was called Raga Rageshri and a key early line was “the smoke coils inside”.

It was undoubtedly Benson & Hedges -- or maybe DeReske or DuMaurier which my mum smoked -- but my English teacher who confiscated my juvenilia from under my desk knew exactly what it meant.

It was 1966 and, despite saying he quite liked that particular poem, he immediately had me pegged for a marijuana smoker. That much he was certain of, but the poem’s title mystified him.

I didn’t try to explain.

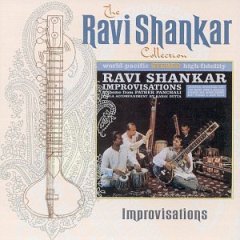

It was actually the name of a side-long track on the Ravi Shankar album Improvisations which I had bought out of curiosity and had fallen for utterly and unashamedly.

As with most people of my generation, I had come to Ravi Shankar through the usual route: the sound of a sitar on the Norwegian Wood, a track on the Beatles album Rubber Soul of mid 65.

At that time I was a member of the World Record Club -- buy three and get one free, if I recall -- and through it had bought an album by the Spanish flamenco guitarist Manitas De Plata after having seen him on television, some blues on the Vanguard label, and various pop fripperies.

And Shankar’s Improvisations (an Essential Elsewhere album here.)

I had no idea what to expect but, at 15, it turned me around completely.

By 66 I had been through late 50s pop and the British Invasion, had picked up on garage bands from the States like Paul Revere and the Raiders, and oddball radio pop like the Tex-Mex sounds of ? And the Mysterians and Sam The Sham and the Pharaohs.

I’d even heard a little Brubeck jazz. (But that's another story.)

But mostly I just loved radio pop music, from Acker Bilk’s Stranger on the Shore to Sandy Shaw, from the Dave Clark Five to Tom Jones.

I was open to anything and, thank God, naively indiscriminate.

But then, one night in my parent’s lounge with the red lampshade and the end of my cigarette glowing: Raga Rageshri.

Since hearing Ravi Shankar’s Improvisations album I have come to believe there is music you knew before you were born. How else to explain the frisson of familiarity and understanding when I first heard Indian ragas, and later music from North Africa which seemed to resonate somewhere deep and unknowable within me?

These days such musics go under the unfortunate tag of “world music”, a taxonomic device I have always felt uncomfortable with. Under that broad banner -- as inclusive as “classical” and “rock” -- is an extraordinary diversity of music, much of it with little in common.

To say you like world music always struck me like someone looking at a colour card in a paint shop and saying, “Hmmm, I like them all”. Just dumb.

Frankly I don’t care for most Cuban music or Portuguese fado. I like lots of music from West Africa, but if Irish music is in the world music category then I’d have to quote Gertrude Stein who said (I could be making this up) “a jig is a jig is a jig”.

Irish music has struck me as being mindlessly cheerful or unbelievably glum. I come from that part of the planet -- born and grew up in Edinburgh so heard Scottish folk, novelty songs like The Cherry Rhyme and the still have an affection for the sound of the bagpipes -- but most Irish music (honourable exceptions like Christy Moore obviously) has never connected with me.

However, Indian music?

It just went straight inside, especially that night in my parents lounge when they were away for the weekend, and I sat cross-legged on the floor in my paisley shirt with the starched white collar, lit the secretive cigarette, and listened to Raga Rageshri, an evening raga.

It had actually taken me weeks to get to this 21 minute track which took up all of side two of that 1962 album. I had spent my time seduced by the three short tracks on the first side. Especially Fire Night which featured jazz flautist Bud Shank.

Inspired by fires in Los Angles the previous year, it is a flickering, incendiary piece with Shank’s flute taking off at almost impossible speed through a melody. It is the sound of flames crackling through dry brush and sage.

I played Improvisations regularly for a year until I found a few other albums by Ravi Shankar.

After shortly after, perhaps by the end of the 60s, I immersed myself in Indian classical music.

If I look at my sagging shelves of old vinyl I can see albums by the sarangi player Ram Narayan, sitar player Ustad Vilayat Khan, sarod master Vasant Rai, and terrific scratchy old thing from 67 called Drums of North and South India which I have played over and over trying to learn or at least understand the complex rhythmic cycles which underpin Indian music.

I have a few albums by Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin, and another of Shankar with one of his former students, the American classical composer Philip Glass.

I also took off on tangents and explored the folk music styles, the Indo-jazz fusion albums by Jamaican-born British saxophonist Joe Harriott from the late 60s, and the stately music of jazz saxophonist John Handy with table player Ali Akbar Khan on Karuna Supreme, the title referring to John Coltrane’s exceptional A Love Supreme. And I listened to the raga-jazz of groups like Shakti lead by guitarist John McLaughlin.

I even made four programmes on Indian music -- tracing a popular path from Norwegian Wood and the raga-rock of the late Sixties through highly ornate and intricate classical traditions, the sound of tabla drums and the vocal traditions. My journey essentially.

Radio New Zealand read the scripts “with interest” they said, but turned the idea down.

The phrase “world music” hadn’t been invented then so they had nothing to hang on to. Oh well . . .

I had a long immersion in Indian music of many forms and only once had a nasty experience. It was on my 21st birthday. To celebrate I bought a dozen scallops the day before from a famous fish shop on Karangahape Rd, and the Krishna album which George Harrison had produced.

I ate the scallops and spent my 21st birthday party in bed throwing up into a bucket while my friends partied quietly in the lounge.

My soundtrack to uncontrollable vomiting was my new Krishna album. It took me a decade to get over my allergy to scallops, and even now I still associate them with that Krishna experience.

The Krishnas came out somewhat better.

I had been fascinated by them, as were many people my age at the time, and in early 71 I wrote to them in London at an address I had seen somewhere.

I didn’t hear back until the start of 72, a letter from Tustah Krishna Das in Bombay.

He offered prayers for my rapid spiritual advancement and said he, his wife Krishna Tulasi, and Purander Das would soon be coming to open a Krishna temple in New Zealand. They would be leaving Bombay on January 20th and be arriving anywhere between two days and one month after, "depending on whether we come by air or by steamer”.

He said he was looking forward to me assisting them with immigration and establishing a temple.

I read this in horror, their arrival would be any day. I couldn’t imagine my parents -- generous hosts that they were -- opening their doors to some Krishnas with nowhere to stay. So I did all I could in the circumstances. I hid.

It was some years before I felt I could show my face at Krishna temples just in case someone felt the bad karma I exuded. But having read so much of their beliefs over the years, and Hinduism in general, I got in to going along to the temple in Mt Eden and sometimes out to the farm in Huia. I was mostly interested in hearing their music, some of which I found ineffably beautiful.

I left them in the blink of an eye however.

One evening at the temple when everyone was dancing and chanting an ecstatic Krishna stood on my son Julian’s foot.

Julian would have been no more than five.

I said to the dancing man, “be careful” but he danced on, oblivious to a child’s tears as he pursued his own higher state.

I never went back.

I sometimes listened to the album, but generally pursued a more pure course through the classical music. I read about it avidly in books I borrowed from the library at Auckland University, and would photocopy pages of arcane detail which I would puzzle over for hours. Then I’d just give up and let the music wash over me, that seemed a satisfactory substitute for knowledge of scales and microtones.

In the early Eighties I learned transcendental meditation from Michael Tyne-Corbold at his home in Mt Eden. He was an interesting fellow -- tall, stooped, scruffy beard and a house full of esoteric literature and rugs from places in the Middle East.

He’d been to Rishikesh to study under the Maharishi Mahesh Yoga when some pesky westerners arrived there for lessons. The Beatles, apparently.

I went faithfully for many lessons and found it remarkable easy.

But even before learning to turn off my mind, relax and float downstream I had done it by myself listening to Raga Rageshri in my parents lounge, the red light dim in the far corner, the music rising slowly to embrace me.

The piece begins with an alap, the opening passages in which Shankar finds his way into the melodies, exploring possibilities, stepping lightly through avenues of expression until he finds the combination of notes which he will develop and embellish. Over the relaxing repeated drone of the tamboura -- a constant backdrop throughout -- Shankar picks at the notes, creating an introspective and slightly melancholy feeling as the strings bend and the melody yawns its way to life.

In this phase of a raga, the first of three, the musician establishes the emotional tone of the composition using the few prescribed notes from which he will then improvise, much as jazz musician like John Coltrane might use the simple melody of My Favourite Things (yes, that one: “raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens“) to create a dense and complex piece of music which, in its final sections bears little resemblance to the tune he started with.

Steadily the melody takes shape, the music rising like smoke, the tempo gradually increasing in the section called the jor where the rhythm is more regular and pace of the music faster. By 15 minutes in Shankar is skittering across his strings, playing a dialogue with himself in two counter melodies. Beneath him the tamboura drones on and the eight sympathetic strings of his sitar -- strings which lie below the four he is playing which vibrate and add resonance, but are not plucked -- add weight and depth. At this point it is hard to believe there is just one musician carrying this complex and constantly re-invented melody.

There is a slight pause, as if for breath, before the final section -- marked by the entrance of Kanai Dutta on tabla drums.

Here the music reaches an ecstasy which is rapid and thrilling as the two musicians play off each other, each pushing the dialogue to greater expression, emotional intensity and complexity.

The raga is now a dizzying swirl of notes, the drums and sitar interweaving their lines likes snakes in a small box.

They play, almost coquettishly with each other (in concert there are smiles and laughter exchanged as each musician sets the other up for a greater challenge) then, after 21 minutes there is the final clack of tabla and post-coital sigh from Shankar’s sitar. And all is silence.

Briefly.

At the end of such a raga in concert there is invariably a outpouring of joy from the audience, people leap to their feet applauding as much from relief as for the genius which has been unwrapped.

And Pandit Ravi Shankar -- the prefix an honorific like, maestro -- is unquestionably a genius.

Shankar played at the Auckland Town Hall in 1981, a concert I felt I had waited all my life for. It was at the height of the anti-tour protests and I, along with thousands of others, marched up Queen St from the old Post Office to what is now Aotea Square.

We shouted and chanted, but when we got to the final rally I peeled off and went in to see a 20th century genius of classical music.

It was a wonderful concert -- spoiled only by the sound of those marching chanting bloody protesters outside.

In 99 I interviewed Shankar, just a phone call to his home in Los Angeles but it was special for me. I was nervous -- how could I not be? -- but it became less an interview than a conversation. I like interviews like that.

His wife Sukanya was profusely apologetic as she had forgotten to mention the pre-arranged phone call to him, but he broke off from teaching his then-17 year old daughter Anoushka (who has developed into a fine player) and was only too happy to talk.

His wife Sukanya was profusely apologetic as she had forgotten to mention the pre-arranged phone call to him, but he broke off from teaching his then-17 year old daughter Anoushka (who has developed into a fine player) and was only too happy to talk.

He was taking her through daily two-hour sessions and I said I wouldn’t ask if she was a good student, but was he a good teacher?

He laughed, a kind of tickling giggle, and said, “Yes, if the students is not … dumb or slow. You know what I mean?

“I can be very bad and angry and a terror to my students if they are not quick in picking up.”

And then he laughed again, a good start to an interview between two people divided by age, culture, knowledge, tradition and distance.

Shankar still took teaching seriously -- he said he had many students, his oldest had been 80 but had died recently -- and in the classical Indian tradition the gurukul system of teachers passing on knowledge to subsequent generations, often to those within their own family, had been the most important threads of the tapestry.

Traditionally teachers were attached to princely courts, often in rural areas, and money was not a consideration.

When he was young it had not been a time of haste, and their had been a different ambience, he said regretfully.

Today however with the principalities gone, the temptations of city life, and the lack of sponsorship, the gurukul system has been progressively eroded.

“The musicians are all in large cities and they are all busy either giving tuition or performing or whatever, and the students have to live on their own. Before they would just stay with their guru and they had all possibilities without thinking of earning money, and their parents gave them away, [that] sort of thing. They didn’t have to think of having to earn money for their family or their parents.”

As we spoke I could hear the sound of a centuries old tradition dying, and was aware that maybe I was speaking with someone who was the last of a particular lineage and school of thought.

That Shankar should still teach -- and he has established his own school in -- means at least his acquired wisdom was being passed on. But for how long I ventured to ask?

He survived a triple by-pass in 86. After five decades of touring and conducting business -- and extra-marital affairs -- he was still pushing himself and performing.

His second autobiography Raga Mala had just been published and I suggested to him that the book, a recent retrospective four-CD collection In Celebration, and an album of his favourite chants had all the look of a career summation.

I put this to him delicately and he could hear the hesitation in my voice. He laughed.

“Not as far as I am concerned. But if my faith decides that, that is a different thing. I am full of beans and ideas.”

And he sounded it.

He laughed, said that by God’s grace his health was all right given what he had gone through -- he was 78 -- and spoke about numerous projects he had.

Shankar was witty -- and candid, candid, except when it came to matters of his personal life.

Our discussion took place a few years before the existence of one of his other daughters -- Norah Jones -- came to light, but in his second autobiography his mentioned affairs with wry discretion. He mentioned the introduction in Hindu which says, “samajhdaron ke liye ishara hi kafi hai”.

“A hint is enough for an intelligent person,” he giggled. “This could have been a sensational book if I had wanted to write all the, you know . . .”

His had been a pretty sensational life anyway: born the youngest of five sons into an upper-class Brahman family in the holy city of Varanasi; little contact with his scholarly father who left his mother before his birth; travelling to Europe and the United States as 10 year old with his brother Uday’s dance company . . .

He met Pablo Casals, Stravinsky, Anna Pavlova, Sergovia, Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie …

In the article I wrote I said turning the pages on his early life is like reading some curiously Indo-version of the Jackson Five.

Uday’s company was feted far and wide, one of the first Indian cultural groups to engage the West, and at age 14 Ravi met Ustad Allauddin Khan who became his mentor and teacher.

Learning sitar at the feet of the master -- Ustad is the Muslim equivalent of Pandit -- meant study and practice 14 hours a day, a life of celibacy and meditation, and fingers that would bled from the steel strings.

Yet he remained seven years under Khan’s stern tutelage, married his teacher’s daughter Annapura (in Raga Mala he admits the marriage was unhappy and that he enjoyed many infidelities) and then began composing scores for films and performing on All India Radio.

The soundtrack to Satyajit Ray’s 1955 film Pather Panchali brought him to international attention and he started touring extensively.

By the time he met Beatle George Harrison in the mid 60s he was well established within the cognoscenti of the Western classical world, but the encounter with the Beatle and the attendant publicity thrust him into the frontline as a musical ambassador for his country, a role he consciously adopted.

“I knew that maybe I could do it, more than anyone at that time. Today there are a lot of Indian musicians who are very well educated. Even more well-educated than myself, who are diplomats and know languages.

“But when I was coming up I didn’t find anyone who that much idea and could communicate.”

But as his star rose internationally he received much criticism back home. Many said he had abandoned the pure tradition -- a charge he vehemently denies then and now -- and that the breadth of his work for stage and film, and bridging the cultural divide by concerts and albums with Sir Yehudi Menuhin, was not appreciated.

“All I can say it was George Harrison’s connection with me which gave me a big push to become so popular with young people. It did help, I am not ashamed to say.

“But I was not swayed by it, and through that I kept my integrity and the music pure, and that is why I am where I am today.”

It is true: in the late 60s and early 70s when hippies and Western counterculture movements were attuned to Indian music and culture he could have become some ersatz guru and peddled some cod-Hindu philosophies along with his own soundtrack to it. But he didn’t.

He was stung by suggestions back home that he had sold out by playing at outdoor concerts like the Monterey Pop Festival in 67, and at Harrison’s Concert For Bangladesh.

“Along with all the respect and admiration I have always seen people, mostly from India, who are envious and jealous. They build up such a strong propaganda, like saying I don’t play any more the pure Indian tradition because I just give a performance for only two hours and I play ragas very short.”

As he spoke of criticisms from over 30 years ago the pain was still palpable. But he countered it in the early 70s the only way he could. He undertook arduous concert tours in India to win back the hometown crowd.

“I went through a period of being very hurt,” he said, “and wanted to prove myself to them, and that I was not a goner completely. So those years I gave them what they wanted, killing myself playing for seven and eight hour programmes, the whole night.”

He spoke about being a traditionalist, and that he had been through the most traditional of all trainings in his music, culture and heritage.

“But because of my childhood it was a blessing to have my eyes opened before even I became fully grown up. That gave me both sides, which is not very common I think,” said this most uncommon man.

Throughout the Eighties and Nineties Shankar pulled back from his pre-eminent position and received the accolades of a lifetime in Indian classical music -- a music he says in his first autobiography takes more than one lifetime to learn.

He has had honorary degrees bestowed on him, his popular song Sare Jahan Se Accha is the unofficial Indian national anthem (although it is seldom credited to him and he berates himself for not being aware of copyright issues when he was younger) and he has received his country’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna (Jewel of India).

Yet latterly it has not been uncommon to hear some deride Ravi Shankar, largely for his dominance in Indian music. Younger players -- tabla player Zakir Hussain, the son of Alla Rakha, recently bristled at his name when we were on a panel discussion together -- have often felt that to outsiders Shankar is the shorthand for the complexity of Indian music and that his dominant position, personality and wealth have blocked the view of others.

If that is the perception, while conceding it is wrong and limiting, that should take nothing away from Shankar’s formidable achievements, both for himself and music he has championed.

Harrison called him “the godfather of world music” and that seems fair.

Without him at least two generations of Westerners would have had little contact with, or understanding of, Indian music. And in all likelihood I would never have discovered one of the sustaining involvements in a life of music, and it hasn’t always been on record from the great artists of our time.

Because of hearing Ravi Shankar’s Improvisations album all those years ago I have sought out and seen great Indian musicians and dancers, many of whom have passed through New Zealand just under the radar of popular interest.

I mentioned his concert in Auckland -- he said he remembered it, loved New Zealand, and then name checked Christchurch, Wellington, and Dunedin “the southernmost part I been” -- and thanked him for introducing me to Indian music and told him how I thought I had known this music from before I was born.

“Yes, but do you not agree with me we find that in so many things. I do it so often I am amazed, although I am not amazed anymore, “ he laughed.

“I am sure it has something to do with previous, whatever you call it, paths or the soul having known about it.”

We talked about the commonality of improvisation between jazz and Indian classical music -- I didn’t know he had worked with saxophonist John Handy -- and also about the ineffable, spiritually elevating paean to Krishna I Am Missing You, one of my favourite pop songs. It was sung by Lakshmi Shankar, and had been included on the retrospective set In Celebration.

I said its beauty was in its simplicity.

“Exactly. And this is something I have always believed. The simpler way can stir the heart. You know, with a lot of curry powder you can cook, but to be able to cook something very simple with almost no ingredients, the way the mothers or grandmothers would cook in the olden days, it is so much more tasty than anything the best chefs can cook.”

It was time to go and he asked me what the time was in New Zealand. I said it was about quarter to four in the afternoon.

“Are you sure it is quarter to four -- or three thirty?”

“Now that I look it’s just after three thirty.”

“I thought so.”

In the early 80s, somehow and somewhere, I met New Zealand sitar player Kim Hegan and invited him to play a concert at a friend’s house. He had studied in India for many years and had a profound understanding of the music.

One night a decade later, before he played a concert at the Pumphouse in Takapuna, I was chatting with him and mentioned that Raga Rageshri was my favourite raga. We agreed it was a lovely piece to be enjoyed in the evening, so restful in its opening movements, yet dramatic and fiery in its final flourishes.

That night he played it -- for me I like to think. The music coiling like smoke then raging like fire.

At that moment I was the only person in the room.

And 15 again.

Ravi Shankar died in December 2012. He was 92.

Jos - Oct 4, 2010

Wow, what a write up!

Save:)

I too loved Ravi from the early days, in fact the first album I ever bought was Axis Bold As love, and the second was a classic Shankar album. A great start I reckon!

Jamie Macphail - Dec 13, 2012

What a wonderfully indepth article Graham, it had passed me by at the time you wrote it, but seeing it today and imagining his spirit transcending, or whatever happens to it, was lovely. My first encounter was through the Concert for Bangladesh, and his combination of skill, humility and radiance was inspirational. I can't remember, did he actually say "If you liked my tuning up so much you will love my performance!" I've often quoted him saying that anyway. Rest In Peace, Ravi, the music lives on. GRAHAM REPLIES: Many thanks, it's a loooong and personal piece (and funny in places I hope). You are right almost, the quote was “If you enjoyed the tuning-up so much, I hope you will like the concert even more.” The music does live on. His recent album is up for a Grammy.

SavePaul - Dec 21, 2012

What happened to Kim Hegan? I went to a concert he gave in Te Awamutu in about 1980. He was just wonderful. GRAHAM REPLIES: Unfortunately Kim stopped playing sitar, went into the family business (promotions) and was very successful. Haven't seen him in a while but he is still around. Last time I saw him he said he was playing again.

Savepost a comment