Graham Reid | | 6 min read

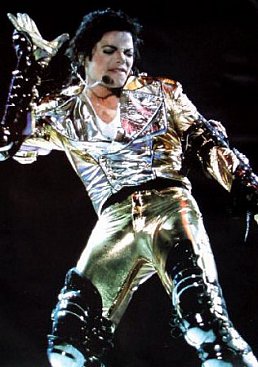

Somewhere around the midpoint of his

often exceptional but undeniably messianic concert in Amsterdam 10

days ago, Michael Jackson fell to his knees and appeared to weep

uncontrollably.

Jackson -- whose stage craft was

impeccable and dancing as exciting as expected -- remained hunched

over and apparently sobbing on the enormous stage for what seemed a

remarkably long time.

But it was a sad moment.

He had just finished singing I'll Be

There, an old Jackson Five number, and on the huge screen behind him

had been projected a series of Jackson Five clips and footage. And

there was the broad-

nosed, cheeky looking black kid that

Michael Jackson used to be, clowning with his brothers backstage,

performing on American television specials, laughing and dancing.

He looked a typical happy child yet, as

we now know from Christopher Andersen's unauthorised biography and

even Jackson's own hints in rare interviews, these were years of

pain, of a childhood denied and emotionally brutalisation by an

abusive, ambitious father.

As the audience of 55,000 in the Ajax

soccer stadium hushed itself into something approaching silence –

punctuated by the occasional de rigeuer scream of “Miy-kaaaal” –

it seemed an opportune moment to turn to Michael Watt whose money was

partially underwriting this tour of Jackson and a support crew of a

couple of hundred and say, “If this guy's really cracked up you're

in serious trouble.”

Watt laughs, the audience remains

silent with expectation and . . . Lo!

He is risen.

Suddenly, Jackson is on his feet naming

his brothers and sister Janet with “I love you all” (noticeably

absent from the list was sister La Toya who broke family ranks and

said the King of Pop should come clean on the child molestation

allegations), then he was off powering through Rock With You and a

show-stopping version of Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough.

Whatever emotion had brought Jackson to

his knees had passed as quickly as it had theatrically arrived.

And the Jackson show -- which runs for

over two hours and touches all musical points in his remarkable

career -- is certainly theatre.

With a barrage of judiciously used

pyrotechnics and other artillery, it comes with the now customary

fact file of statistics that accompany any stadium rock show these

days: a stage weighing almost 10 tonnes which spans 70m and takes

three days to construct; 4000m of cable linking the lights; speakers

and pyrotechnics; a travelling production and personnel team

numbering almost 200, over 200,000kg of equipment . . .

Yet despite that blah-blah of

statistics this HIStory World Tour concert -- named for his last

album, and which doesn't take in the United States as part of the

“world” -- doesn't fall prey to gratuitous lighting displays and

a fire-fight of explosions. When the fires start, machine-guns rattle

and the big gun rolls out - literally - they are all part of a

tightly scripted, brilliantly choreographed event.

And Jackson's show is certainly An

Event.

From the pre-concert tapes of classic

Motown hits -- Jackson clearly linking himself with the lineage of

great black music - through the militaristic choreography of the

opening numbers (much flag waving and precision marching/dancing,

heavily borrowed from sister Janet's recent career it must be noted),

the HIStory show lends itself to analysis beyond the enjoyment it

undeniably provides.

As with the Queen, the 38-year-old King

of Pop seems to have always been with us and his 30-year career can

now be reduced to iconography: the moonwalk; the bejeweled glove; the

hat; the wind-blown white shirt over the white T-shirt . . . These

and other images are familiar to us.

Who doesn't remember that brilliant music with producer Quincy Jones, the Thriller video or Billy Jean and the moonwalk dance?

Through video montages projected on the

enormous back-screen the HlStory concert reminds us of all these.

It is also video made flesh in places

as Jackson, in a series of set-piece dance routines and frozen poses

under the spotlights, both recalls and embellishes the images which

have imprinted themselves in our collective consciousness.

And Jackson, with canny stage

sensibilities, daringly recreates these images and often surpasses

them: here the on-stage video is projecting just the glove onto the

25m-high screens at the sides of the stage; then it is simply on his

feet, later it freezes the image of Jackson standing in a whirlwind

of dry ice which mimics his appearance at the Superbowl three years

ago . . .

And Jackson, with canny stage

sensibilities, daringly recreates these images and often surpasses

them: here the on-stage video is projecting just the glove onto the

25m-high screens at the sides of the stage; then it is simply on his

feet, later it freezes the image of Jackson standing in a whirlwind

of dry ice which mimics his appearance at the Superbowl three years

ago . . .

To invite comparisons with your video

is a risky business in pop – witness the number of live acts who

are unfailingly disappointing after their clips – but Jackson

matches them point for point.

His dancing, full of that angry energy

few others have even attempted, is little short of astonishing. But

of equal note is his voice, of ringing clarity in the ballads,

searing in material like Billy Jean and Smooth Criminal -- which

comes complete with Depression-era suits and a choreographed

shoot-out that recalls the St Valentines Day Massacre.

And Jackson's show doesn’t shirk from

its violent aspects: torchlight and uniforms of fascist persuasion

early on; S&M masks in Come Together; mass destruction that

echoes both the fall of the Berlin Wall and, perhaps to a lesser

degree but equally, appropriating from the pop culture of Pink

Floyd’s The Wall . . .

At the centre at all times, however, is

Jackson, his band reduced to anonymity behind him, except in sections

where he quits the stage and leaves the video projections to carry

the imagery. It is these montages -- Jackson clips intermingled in a

post-modernist's nightmare with pictures of starving children, Nelson

Mandela, Mother Teresa and others -- which slow the momentum of the

show and also reinforce how much Michael Jackson has become dependent

on placing himself at the emotional and political centre.

Jacksons world view -- often laughable

in its simplicity, some would say disturbingly Christlike as well --

is distilled in his songs. While he may not directly address his

audience (no “Good evening Amsterdam!” tonight) his gestures and

lyrics are general if not universal.

There’s something appealingly

inclusive for an audience, especially those who feel emotionally

disenfranchised, in songs which say, “They don’t care about us",

“What about us?" and “You are not alone."

But when Jackson ends his rock’n’soul

concert with an image of himself as possible political martyr and a

galling image as the Light of the World and saviour of the suffering

children, it is too much to swallow.

You have to admire his nerve, however:

he has consciously reminded you in that Jackson Five footage that the

message “it doesn’t matter if you’re black or white” is

hypocritical; that the distinction between reality and fantasy is

blurry if non-existent in his world and that crowd manipulation,

sometimes cynical, is just part of the contract now.

The tragedy is, the HIStory concert

rides on a soundtrack of some of the finest rock’n’soul music of

the past two decades and is fronted by a dancer who has won the

admiration of Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire and more than a decade of MTV

viewers.

There's an old joke about rock'n'roll:

it's entertainment, it isn't about world peace.

Yet Jackson -- for all his manifest

brilliance as a performer and songwriter -- admirably, sadly and

somewhat naively perhaps, thinks (or wants us to believe) it is.

In Michael's enclosed world, maybe it

is?

post a comment