Graham Reid | | 6 min read

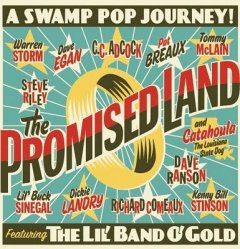

Lil Band o Gold: Teardrops

C.C. Adcock has done a lot of living in

his 34 years, from playing in bands around his hometown of Lafayette

in southern Louisiana when barely into his teens to making a

glam-metal noise in LA, then backing the late Bo Diddley and Zydeco

legend Clifton Chenier to hanging out with the undead . . .

Yes, these days Adcock's music is used

in the steamy swamp drama True Blood to conjure up those dark

doings down in the mists of bayou country.

He's just come back home – “looking

forward to cocktails and dinner” – after working out some music

for the season finale and a doco being shot about his band, and he

laughs when he recalls his first encounters with the television

series.

He thought he'd check it out before

lending some songs to make sure it wasn't “shameful”.

“But it was so ridiculous, over the top, silly, camp and perverse that I thought, 'It's kinda is like home'. It was just completely blown out the way people down here like to blow things out.

“You have dinner down here and we

take a pork chop and stuff it with more pork then put a crab on top

stuffed with crawfish with a cream reduction sauce which has shrimp

in it . . . We like to overdo things down here – you can look at

our waistlines and tell.

“But I was just up in north Louisiana

where I have family and that is real different to us, and that's

where [True Blood] is supposed to take place. I was in this old bar

and thought, 'This is out of control up here, that show ain't that

far off', and these people weren't acting.

“So I've been more than happy to

create music for it, and I like to go to that over-the-top place too

when I make music. Lil' Band of Gold is a ridiculous idea in some

ways.”

But while Lil' Band of Gold – a

swamp-pop supergroup which has drawn in regional stars to make a

kicking gumbo of rock'n'roll, Cajun, swamp rock, blues and southern

soul – may be ridiculous, it is also a hugely popular idea which

has been the subject of a doco The Promised Land and has seen them

embraced by people like Marianne Faithful (on whose new album Adcock

is working), Nick Lowe, audiences at South X South West and Byron Bay

in Australia . . . and is now on its way here to bring party music

and southern-fried soul.

Many decades younger than the heroes

who Adcock and accordion star Steve Riley invited into the band –

among them the legendary singer/drummer Warren Storm – Adcock admits they had their own agenda.

"Steve and I just wanted to sing with Warren every night. We were aware that in our careers or whatever we had going we kept getting told 'You got to sing a little better' so we thought, 'Let's go hang out with Warren'.

“When we started it was to make music

and play songs we loved and you can't get any better than real –

the real guys who sang on the records that you really dig. The next

thing you know, even with my cockamamy part on it, it still sounds

like the record.

“Warren's famous down here. We had

regional radio – we still have a lot and it is becoming

specifically regional like just playing south Louisiana music, and

that's cool -- but back in the day Warren Storm got played next to

Rod Stewart. From the beginning of rock'n'roll down here in New

Orleans, Lake Charles and Lafayette, and in Houston and Mobile, DJs

played regional stuff and they broke records that became worldwide

hits.

“A kid makes a record in a local shop

and brings it in to the station – just like Elvis did with Sam

Phillips – and they play it. And next thing you know the genie is

out of the bottle, so we grew up with that.”

What kids in Louisiana also grow up

with is a respect for their local music, be it zydeco, Cajun, soulful

ballads or rock'n'roll. This is music they hear at home and see

played everywhere, so for Adcock to admire people many decades his

senior and want to play with them is not unusual.

He attributes that to so much music

being played and it being a part of people's lives.

“Music is a way of life down here,

you don't have to be a 'professional' musician to play music. Family

members, butchers, school bus drivers, uncles – everyone plays. So

you have these family gatherings or festivals and you get guys who do

a job during the week but on weekends play in these great bands and

they've made records.

“So you want to impress the grown-ups

and you'd have uncles or friends of your parents who you thought were

cool and they'd break out a guitar – and if you could get in on

that you could stay up a little later, just hang out and be one of

the grown ups. It starts there.

“It also has a lot to do with so many

of the old cats around here are just so bad-ass. At a very young age

you're struck by that. You don't wake up and think they are old

fogies, they can still kick ass and drink and party. That's what

makes it part of our culture, and it all comes from these people.”

Adcock and Riley started to informally

pull together what became Lil' Band of Gold in the late 90s to jam

and play local dances – members came and went – and through Tarka

Cordell (son of the famous British producer Denny Cordell who

recorded the early Moody Blues, the Move, Joe Cocker, Procol Harum's

classic Whiter Shade of Pale and started Shelter Records with Leon

Russell) they made their debut album The Promised land (“8 members,

25 egos, 6 livers”).

They covered classic Southern songs

like the late Bobby Charles' I Don't Wanna Know, Evangeline Rock,

Allen Toussaint's So Long and Teardrops alongside roadhouse

rock'n'roll originals (with a swamp pop twist).

In the background of the core line-up

they have collectively played with everyone from Etta James, Joe

Cocker and blues legend Lightning Slim to Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger,

Laurie Anderson and Paul Simon.

This multi-generational swamp pop

supergroup started taking their get-up'n'dance show as far as

possible.

“But there's plenty of places to play

right here in Louisiana so it was pretty hard to convince Warren we

should go to Australia on a Saturday night when he could play to a

packed house here, to the same people he's been playing to for 50

years. He played their high school proms and they've grown up and

grown older with him. So it was hard to convince him we should make a

40 hour flight [to Byron Bay Festival], but he had such a good time

now he can't wait [to tour].”

Adcock admits there was no master plan

when they started playing local dances, but the opportunity to take

their culture to the world and expose great regional talents like

Storm, saxophonist Dickie Landry and Pat Breaux and others to the

world was too great to resist. And it's not like it's a chore.

“Rock'n'roll, having a good time and

having a few generations of people get on the stage together? Any

community and culture can relate to.

“You probably got your own Lil' Band

of Gold right there in your neighbourhood. They might not be together

but maybe someone will see us and think, 'Man, I gotta go down the

street and start playing with that cat because when I was a kid my

dad said he was the guy'.

“The reason it works is because

people like hanging out with people from different eras. And things

are moving so fast now – not only for my generation but people

younger than me – and it's cool to be able to get a snapshot of the

way things used to be done. And to not only be intrigued by that but

realise, 'Man, the way it used to be done still works'.

“That's the boogie.”

post a comment