Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Cindy Lee Berryhill: Damn, I Wish I Were A Man

In the early Nineties – three decades

after the original urban folk movement in Downtown – there was a whole new neo-boho scene

in New York. Michelle Shocked was just the first and copped the

publicity but behind here were Kirk Kelly, Roger Manning and Cindy

Lee Berryhill -- all of whom dressed like fashionable

alternative-Eighties types (black jeans), played like early Bob Dylan

(acoustic guitars and harmonicas were de rigueur) and called on that

traditional folkie lineage of Woody Guthrie, Phil Ochs and so on.

They are all largely forgotten these

days and in truth they didn't really make quite the impact the media

was tipping for them, but even if you didn't – or don’t – like

folkies, this crew was quite interesting.

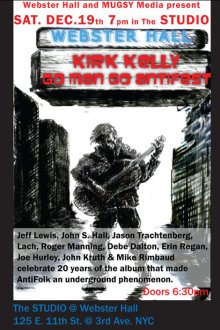

These folk-punks had as their principle

the title of Kelly's debut album Go Man Go -- an appropriately

Kerouac-shaped phrase which he followed up in the lyrics with “and

don’t look back,” which placed him unashamedly on the Dylan axis

when you recall the name of Pennebaker's film on Dylan.

Unfortunately, on the evidence of Go

Man Go (the album), Kelly was too much the sloganeer and tied to the

Dylan's style for anyone to throw accusations of originality at him.

His publishing company was Rambling Woody Zimmerman - and that left

him very little room to move.

Make your way through Talkin’ Train

Blues (with its overt reference Dylan's It Takes A Lot To Laugh (It

Takes A Train To Cry) and a song to union activist Joe Hill (were

there no more contemporary martyrs to the union cause?) and you’d

be forgiven for thinking Kelly didn't have any more to say than the

old troubadour did himself.

He did, but it wasn't much. Corporation

Plow sung over a slack bass played by producer and ex-Violent Femmes

man Brian Ritchie is a good stab at understanding the plight of

farmers during the silent Industrial Revolution of the 20th century,

and in Red Blues he cleverly looks at South America, says he doesn’t

“want to be no communist", and concludes, from the

Reagan-Contra thing that it's better to be a fascist.

But he shoots himself in the foot again

when he writes Marching Off To Gaul, which is little more than Buffy

Saint-Marie's Universal Soldier sung from the soldiers perspective.

Of them all in the neo-Boho movement,

Kelly was the banner waver but a disappointment.

Roger Manning was more problematic. He

delivered his cynical songs like a young Loudon Wainwright (that's

good) and seemed to be the unofficial recorder and in-house

smart-alec of the movement.

On his self-titled debut album (also on

SST like Kelly), he casually name-checked Shocked (and the phrase "go

man go") and was the kind of desperate guy who accuses his

girlfriend of abandoning her country when she says she's leaving him

and going to live in England. His lyrics have plenty of nifty lines

of such self-deprecation.

But he struggles with serious issues,

too.

He’s the one who says he hates boring

lefty folk-singer rhetoric “because it's either ‘no more bombs'

or 'no more nukes' " then grudgingly concedes “they were right

about Vietnam" before flipping over again to conclude “but

then again, they were the only ones (who) gave a damn."

He also gets in a nasty twisted

narrative where a friend's comment about a woman, “I don't want no

girl that wears leather like that," gets the snaky rejoinder

from Kelly, “Me, I don‘t care -- so long as she don’t smoke in

bed.”

Manning is funny, sassy and vicious

where necessary but, like all these neo-folkies (and the old school

come to that), he misses his targets too.

“Sometimes I get the feeling' I just

want to go to France and just hug a cathedral” doesn’t say much

other than something about its own cleverness.

In those feminist-conscious day (post

Sixties feminism, post-punk too) he admits his shortcomings too. A

woman says “seems like I belong nowhere." His reply?

"Nowhere is everywhere – hell,

that was easy”

The tag there shows he's a smart-alec.

Roger Manning is the man and that album

is worthy of re-discovery.

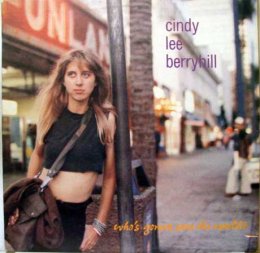

But the star turn was Cindy Lee

Berryhill, whose album Who’s Gonna Save The World is the most

coherent.

A displaced Californian who kicked

along with an electric band for preference, she came off closer to

Patti Smith than Joan Baez and had a finely-tuned sensitivity to

post-feminist consciousness.

Her Damn, I Wish I Was A Man takes an

astute poke at Kerouac (and by trickle-down theory, Kelly) and that

whole "just go" idea. It ain't quite that easy if you’re

a woman, obviously. It’s just boys escaping manhood and

responsibility -- yet again, you can almost hear her sigh.

Whatever Works fires a broadside too:

"It's a dirty job and some Ivy League white male’s got to do

it, like travel, speak foreign . . .”

She knows her targets -- folkies who

write on notepads in nice apartments aren't immune either -- and she

seldom misses.

Lyrically she's a heavyweight compared

with Kelly and Manning. She takes on heroin (Steve on H with a

powerful free-form Patti Smith improv) and a lot of tough-minded

songs about young women whose dreams are betrayed until they are

“over the hill at 21 . . . the anvil fell, went straight to hell, I

had to get a job."

She puts herself into any place, be it

a young girl's heart or a garage band ("they met at a friends to

the sounds of Johnny Rotten") and comes through the fire

unscathed.

Of all the neo-Bohos – and there were others – she’s the one to hear, and by some irony she sings Kirk Kelly‘s best song, This Administration.

You sense from Go Man Go that Kelly would have hashed it clumsily.

He was wise to toss it to Berryhill.

Cindy Lee Berryhill is still out there (see clip below) and still has something to say.

But there is a freshness, anger, cynicism-with-humour on Who's Gonna Save the World which makes it worthy of a re-discovery.

She's a powerhouse.

So good she probably wasn't even a folkie - if you get

my drift.

post a comment