Graham Reid | | 6 min read

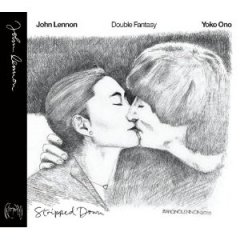

John Lennon: Woman (from Stripped Down)

In what would be one of his final

interviews around the release of Double Fantasy in late 1980, John

Lennon said – as a married, settled man at 40 with a young child –

he was interested in seeing if it was possible to have a life centred

around a family and a child and still be an artist.

“Could the family be the inspiration

of art, instead of drinking or drugs or whatever?”

Regrettably most of the evidence of

Double Fantasy -- and to a slightly lesser extent on the posthumous

release Milk and Honey pulled together by Yoko Ono from tapes for

that proposed companion-piece -- the answer was, “Not really”.

Pleasant though some of Lennon's

melodies were on Double Fantasy – and there's a good case to be

made Ono's songs were the more interesting – the lyrics were often

trite and resorted to cliches. Disappointing from a man who coined

lines like “tangerine trees and marmalade skies”.

In a bruising NME review Charles Shaar

Murray wrote that the album was “a fantasy made for two (with a

little cot at the foot of the bed)” and concluded “Now bliss

off”.

Within a month Lennon was dead and the

album was at the top of the charts.

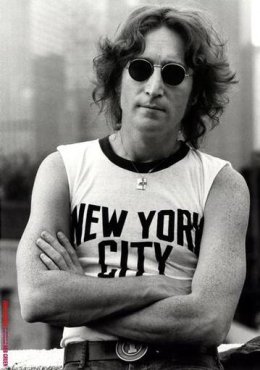

Lennon's solo career – 10 years and

during four of those he released nothing, didn't even have a

recording contract – has always been the stuff of argument: his

astonishing Plastic Ono Band album of 1970 stands as one of the most

courageous in rock for its pained honesty and blunt “I don't

believe in Beatles, the dream is over” statement.

He didn't spare himself – and in

excoriating songs like the brilliantly cathartic Well Well Well he

didn't let his listeners off lightly either.

But albums like Imagine (the peace

anthem sharing vinyl with his vicious attack on Paul McCartney in How

Do You Sleep?), Mind Games (some dreary workmanlike rock'n'roll

alongside the elevating title track and the sublime, ethereal #9

Dream) and the political rhetoric of Some Time in New York City

(which was dated on release and full of sloganeering) have always

tested those for whom he would always be Beatle John.

Had he lived he would be 70 in October

2010 and on the evidence of his domestic bliss (which may not have

lasted, Milk and Honey ha some less than cheerful stuff from both

parties) he might not be out there like Bob Dylan making interesting

and often compelling music.

If he went the whole covers route like

Rod Stewart it's more likely he'd be doing Little Richard and Jerry

Lee Lewis (or the music hall acts he seemed to enjoy) than Gershwin.

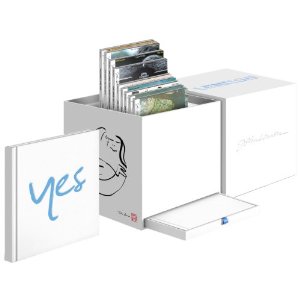

But his birthday allowed a

re-consideration because – perhaps for the last time in her life,

she is 77 – Ono has overseen another Lennon re-issue on a

significant anniversary. Previously there had been the four CD Lennon

Anthology, but this one is different: all the original albums (no

extra tracks) have been digitally remastered, there is a disc with

rarities and outtakes, and Double Fantasy appears also in a Stripped

Down edition in which much of the embellishment has been removed to

lay the songs more naked.

So is this reissue-cum-marketing

exercise of interest?

Ordinary songs are made no more special

by remastering but many which might have slipped by – among them a

few from the often-overlooked Walls and Bridges of '74 – are given

a new dimension and presence.

Most interest alight on Double Fantasy:

Stripped Down however, and especially Ono's racks like Kiss Kiss Kiss

and, especially, Give Me Something which have had an overhaul to put

them more in line with her brittle and astonishing single Walking on

Thin Ice, the tape of which Lennon was carrying on the night he was

shot.

These songs are spark like static

electricity – and Every Man has a Woman Who Loves Him comes off as

a completely new song, and not for the first time. In '84 on the

occasion of the tribute album to Yoko of that name (which had Ono

covers by Elvis Costello, Harry Nilsson and others) she simply pulled

back her vocal part so it became more a Lennon song – and was

attributed as such.

This time out it is reconfigured as a

slightly disturbing ambient dreamscape.

You could argue that the remixing and

stripping down of Double Fantasy favours Ono more than Lennon: his

Starting Over does sound more true to the spirit of Fifties

rock'n'roll and both Woman and Watching the Wheels less wrapped in

the cotton wool of orchestration and backing vocals, but they don't

come off as significant rediscoveries the way these Ono songs do.

For that new view of Lennon's songs you

need to look elsewhere.

The Plastic Ono Band album still sounds

stark although more immediate, but I Don't Wanna Be A Soldier on

Imagine now sounds more menacing and disturbing as the guitar parts

are separated out, although curiously Gimme Some Truth sounds

less than impressive. This is one song which should have leaped out

at you in a remaster.

How Do You Sleep? and the spare ballads

Oh My Love and How? have much more presence, the latter two becoming

real rediscoveries for their quiet melodicism.

In that regard, Mind Games is where the

jewels lie: the title track is still a mysterious work and soars

gloriously, Tight A$ is sharper all round and a terrific rock song,

but the beauties of Out the Blue and You Are Here (with guitar by

David Spinozza given more attention) are joyous revelations.

And on Walls and Bridges the lovely Old

Dirt Road (with Nilsson), #9 Dream and Bless You remind you what a

great melody writer Lennon could be – and how convincingly he could

deliver them. These are wonderful and warm songs.

The Rock'n'Roll album certainly has

much more life about it, but little on Some Time in New York City was

of much merit anyway – although the live disc now restored, it was

omitted from some reissues) is useful neighbour-baiting noise.

In the large Signature Box edition of

this collection (all the albums available individually) there is also

a disc of “home tapes”, most of which are alternate takes of

songs from Plastic Ono Band or Double Fantasy – but among these are

a stab at Honey Don't which Ringo coverd in Beatle days (recorded by

Lennon during Double Fantasy sessions) and two oddities: the possibly

autobiographical wish of One of the Boys (“ but he's still one of

the boys” which has appeared on The Lost Lennon Tapes) and India

India which sounds like it might have been written during the

Maharishi sojourn (it's a folksy piece about the beauties of India

but his love – the unnamed Yoko – is back in England) although it

was clearly recorded much later. Perhaps in the few years before

Double Fantasy. Both are minor works of little interest other than

for their lyrical content.

So, Lennon's on sale again – and

perhaps for the last time.

It is hard to imagine what else can be

hauled out of this well. (Remastering of the posthumous Live in New York City and

Menlove Ave, perhaps? Most of the latter is already done.)

Was this re-presentation a cynical

marketing ploy to take advantage of a significant anniversary: in one

sense, of course. An anniversary allows for a degree of relevance.

But most of this music stands on its

own merit – and, as with the similar Beatles project, was thoroughly deserving of this remastering.

And the smart ones will be selectively

pulling the remastered Ono tracks from Double Fantasy and Milk

and Honey for a terrific compilation.

Not quite what you would expect from a

Lennon reissue mid-wifed by Yoko Ono, is it?

Or is it?

Phillip Magee - Oct 18, 2010

I think you have summed up what was a very patchy solo period spot on. John's legend as the "interesting" Beatle seems to have led to his solo work gaining a lot more kudos than it deserves. "Double Fanatasy" seemed thin thirty years ago and time has not enhanced what were workman-like songs then. "Mind Games" stills soars and "Whatever Gets You Thu the Night" stills makes my feet move. The hippy-dippy "Imagine" seems well at odds with some-one who treated his first wife and child with calculated coldness and then disappeared for a long period on the second. Perhaps Paul should have had more public affairs and more interesting drinking buddies. Bu I'm not sure anything would make up for "Mull of Kintyre".

Savepost a comment