Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Time Zone (Afrika Bambaataa, Bill Laswell, John Lydon): World Destruction, Industrial Remix (1985)

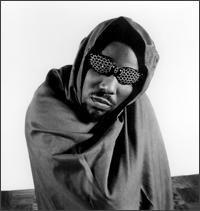

He answers the phone exactly as you

might expect - a booming, stentorian tone like some Old Testament

prophet and commands: “Speak.”

We speak . . . and the voice changes

into the quiet tones of unassuming politeness as he patiently

explains his political philosophy -- and there's a lot of it.

For this is Afrika Bambaataa, head of

the Zulu Nation, an organisation of New York gang affiliates formed

in the mid-Seventies and now hip-hopping and funk-hopping on the

charts.

Bambaataa has just returned from an

extensive European tour and heads back again in a fortnight to

promote his new album The Light and his latest single Reckless, which

features members of UB40.

“People don't want to think about

religion too much, they think they're so modern with all this

technology. But it’s all written in your Bibles and Holy Korans

that certain things will happen at this time but you've got to look

at your past to see what's happening in the present and that’s why

I write certain songs

“But if you start speaking

message-type songs some people don’t want to let those kinds of

records go too far. I try to make records which wake up minds because

it’s getting heavy out here with racism' and poverty and wars.”

All this religious philosophy sounds

pretty heavy on a phone line, too, and you can see why hip-hopper

Roxanne Shante has said, “People have got fed up with being

lectured as if it was their mother and father. Who wants to go to a

party and be lectured? You can stay at home to hear that."

True enough, but Bambaataa combines the

message with a killer dance floor groove and he isn’t going to stop

just because some people don't like to hear what he’s saying.

He's been going his own way for too

long now.

Running wild in the South Bronx

streets, he grabbed on to music in the early Seventies and started

DJ-ing while still at school. His style then, as now, was to take the

best grooves and pull them together.

Along with Grandmaster Flash, Bambaataa

is credited with creating the first phase of rap and hip-hop. But

even then he was taking the music elsewhere when he fell under the

influence of Black Muslim teaching: “I was heavily influenced by

the beliefs of Elijah Mohammad and the teachings he gave Malcolm X

and Muhammad Ali and others. Everything he said about dealing with

life, nationalities, religion and self.”

“The Creator has sent prophets and

messengers to warn everyone to get back to righteousness and he has

also done it through music with prophets like Bob Marley, Sly and the

Family Stone and John Lennon who tried to wake people up to what's

happening around them.”

So Bambaataa's message is one of

universal love . . . and bop till you drop. He figures if you hit

people though the feet then their heads will follow.

“Some people don’t want to hear the

message so you put something in there for them to dance to. They

might dance 10 or 20 times and still never hear the words but then

something might just grab them and they’ll hear words like ‘world's

racial war’ and want to know what I'm singing about,"

The dance groove Bambaataa was laying

down wasn't heard on record until 1980, however when he recorded Zulu

Nation Throwdown Part One for the small Paul Winley Records label. He

then shifted to the Tommy Boy label and under the eye of Arthur Baker

recorded the funk-phenomenal Planet Rock 12.

Planet Rock is considered a milestone

in the funk world and his next release got to an even broader market

when it was picked up for the soundtrack of Beat Street.

In the following few years Bambaataa

turned himself into one of music’s foremost collaborators. He

recorded with James Brown and John Lydon and the new album rings in

Nona Hendryx, Bootsy Collins, Sly and Robbie, George Clinton, Boy

George and others.

Whatever direction Bambaataa goes, he

ties it all to some kind of social philosophy, often a little off-the

wall.

World Destruction, with his band Time

Zone and featuring John Lydon, was inspired by seeing a film on

Nostradamus and Bambaataa is still convinced we are living in the

last days.

"He [Nostradamus] said there would

be a war between Islam and Russia with America, and you can see than

happening already. There aren’t going to be any

communists-versus-Americans because you can see the Russians and

Americans are cooling out, and the Islamic nations are rising up.

“That's why I wrote World Destruction.”

He launches into a lengthy

domino-theory analysis of confrontations around the globe which ends

with nuclear explosions and people fighting their local police

forces. It's wild stuff but Bambaataa speaks with powerful conviction

and then fires off a salvo in the direction of ghetto problems.

“It's getting worse growing up now

with this new drug called crack. I’ve been all over Europe telling

people if they see people bringing this stuff in -- I don’t care if

it’s from the Government on down -- they must be destroyed.

“This drug will mess up families,

your daughters will become whores, some of your male people will

become dissatisfied with themselves and end up killing your children

or grandmother.

“This drug is serious so don't let it

into your country.”

Bambaataa is on a roll and the words

don’t stop coming.

"Everyone needs education and to

get rid of the history books they've been using and write the truth

and show what really happened and what black people in Africa, the

Chinese, people in New Zealand have given to the world.

“That will mean new generations will

come up and won't hate. They may not love each other but at least

they'll respect each other.”

Bambaataa's vision of the world-to-come

infiltrates everything he does. He keeps his eye on record companies

which he says are “ripping off rap artists like they did with

doo-wop" and "people who have jumped in on hip-hop because

of the money."

And he has left behind companies which

haven't been in behind him. But he’s a hard man to pin down

musically and claims the techno-pop of Kraftwerk and the Yellow Magic

Orchestra as his influences as much as James Brown or George Clinton.

“A lot of people will be confused by

The Light album. It's not hip-hop, it's dealing with different brands

of funk, like electro-funk, go-go funk, hard-core funk, reggae-funk,

and so on. I try not to get categorised.”

No chance, sir.

“But I’m happy with my new company

-- they let me be free,” he booms.

And with Afrika Bambaataa feeling happy, we can all sleep a little easier in our beds.

post a comment