Graham Reid | | 8 min read

At 66, Bob Dylan has been through many musical changes in the course of his career, from fresh-faced young folkie to senior statesman of his generation. He's been folk, what we now call alt.folk, folk rock, psychedelic rock, rock’n’roll, country, alt.country, troubadour, country and western . . .

And he made movies, changed hats and jackets as often as he changed his musical style, and tours restlessly.

Here’s a fast survey of Bob’s back pages.

BOY FROM THE NORTH COUNTRY

Born in 1941, the young Robert Zimmerman was the right age to become a teenage fan of Elvis, Buddy Holly and 50s rock’n’roll. He was also infatuated by the Beat Generation of Kerouac and Ginsberg. In his high school year book in 59 the picture caption recorded his ambition as “to join Little Richard’s band”.

The Turning Point: He read Woody Guthrie’s autobiography and, having changed his name to Bob Dylan, hitched rides to New York City to see the dying folkie in 61. He established himself as Guthrie’s friend and follower, played folk clubs in Greenwich Village, wrote Guthrie imitations until he found his own socio-political style in songs like Blowin’ in the Wind. He also immersed himself in the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music (traditional folk, rural blues) which provided him with a foundation for his own songs.

The Look: Jeans, open-neck shirts, harmonica around the neck. Sometimes a cap. Hair starting to struggle from the close crop. Your archetypal Boho-hobo fresh from ridin’ the rails.

Essential Listening: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (63); The Times They Are A-Changin’ ('64).

Also: The recently re-issued DVD Dont Look Back, film of Dylan’s 64 tour of Britain which shows Dylan in the brief period when he was approachable, witty (more witty than acerbic, despite legend and myth), and commanding huge stages with just his presence, a guitar and a harmonica. As commentators note, that had never happened before, and has happened seldom since. It was the last time Dylan revealed himself so nakedly to his audience.

IT AIN’T BOB, BABE

Hailed as the voice of his generation for poetic songs such as The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Blowin’ In The Wind, Dylan became increasingly uncomfortable at the pressure from old folkies (like Pete Seeger) who saw him carrying their torch to the new generation. The falsified and fanciful life story he invented for himself was questioned, he became more withdrawn, looked to the success and sound of the Beatles and the Stones, and because he had initially been a rock’n’roll kid in love with Elvis and Buddy Holly he naturally plugged in electric guitar. Combining the electric sound with his poetic lyrics, in a stroke he invented literate folk-rock -- and was reviled by former fans.

His six minutes-plus single Like A Rolling Stone is widely considered one of the best rock songs ever written.

The Turning Point: At the Newport Folk Festival in 66 Dylan brought on an electric band and were booed. In less than 20 minutes Dylan farewelled the folk scene which had created him, but was ultimately stifling.

The Look: Shades permanently attached, tight black pants and jacket, the famous polka-dot shirt. Hipster cool with a touch of Camus and suggestions of serious knowledge of illicit drugs. Hair now teased out. The classic Dylan look.

Essential Listening: Highway 61 Revisited (65); Blonde on Blonde (66)

Also: The Martin Scorsese documentary No Direction Home is a detailed account of Dylan career from his hometown to becoming a rock superstar. Greil Marcus’ Like A Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads is an insightful account into the context and writing of that classic song.

THE DRIFTER’S ESCAPE

By mid 66 Dylan’s life was being live at, and on, speed. He had to stop and he did, abruptly. In 18 months away from the public he rehearsed with The Band, his music took a more homely, mellow and country-styled turn. When the world was hippie, day-glo and playing Sgt Peppers, Dylan returned with the acoustic album John Wesley Harding full of dense lyrics with Biblical references.

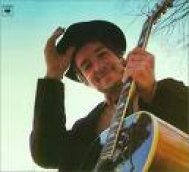

The Look: Wire frame glasses, rural comfort of the 19th century kind, suggestions of a travelling preacher. Wispy beard.

The Turning Point: On July 29, 1966 was riding his Triumph motorcycle, was blinded by the sun, braked too hard and flipped off and cracked some vertebrae. He retreated to upstate New York with his wife. There were rumours he was dead or paralysed. His enforced period of recuperation allowed him to step away from the madness that had surrounded him.

Essential albums: John Wesley Harding (67); Nashville Skyline (69); The Basement tapes (released in 75)

Also: Sam Peckinpah’s 73 western Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid in which Dylan plays an enigmatic character named Alias, and for which he also wrote the loose, acoustic soundtrack which included Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.

THE JOKER’S RETURN

In 75 Dylan released his return-to-form album Blood on the Tracks, and went on the road with The Band, then later with a travelling circus called the Rolling Thunder Review during which he knocked classics from his catalogue into different shapes (Blowin’ in the Wind as a reggae song). Also wrote Hurricane about jailed boxer Rubin Carter.

The Look: From the preacher to travelling show and carnival chic. White facepaint during the Rolling Thunder Tour. Waistcoats, scarves, gypsy-suave towards the end.

The Turning Point: Dylan separated from his wife Sara, was emotionally rootless, buried himself in writing, touring, drink and cocaine. Reconnected with the rock world through stadium tours.

Essential Listening: Blood on the Tracks (75); Desire (76)

Also: The Rolling Thunder Logbook which writer Sam Shepard catalogues the craziest mobile musical party of the mid 70s. The surreal film Renaldo and Clara (78) also captures this strange period of Dylan with a white-painted face, and Ronnie Hawkins playing a character called Bob Dylan. At four hours long it died in a short cinematic run.

THE MESSENGER

In the late 70s Dylan lost most of his audience when he released a series of albums which revealed him as a born-again Christian. He would preach in rambling messages on tour, and the lyrics on the albums suffered from being lifted from scripture.

The Look: Conservative but unapproachable. Shades and sometimes thin scarves.

The Turning Point: At a concert in San Diego a fan threw a cross on the stage which Dylan picked up. He had already been reading the Bible and his girlfriend at the time was a member of a Christian fellowship. The leader became a follower. Then he re-embraced his Jewishness. Strange times. For Dylan and the few loyalists remaining.

Essential Listening: Street Legal (78); Slow Train Coming (79)

Also: Howard Sounes’ book Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan is good on all aspects of the singer’s career but offers rare detail and insight into this period.

WHEN DID YOU LEAVE HEAVEN?

In the 80s Dylan seemed rudderless: now a non-Born Again, his new songs often sounded like throwaways; albums were quickly and poorly recorded; he made a silly “rock” movie Hearts of Fire; had people like Sly‘n‘Robbie, Slash from Guns N‘Roses, and various ring-in on his albums; and wore dreadful clothes. He was lost and only Oh Mercy from this period suggests that he still had a gift. But he followed it up with Under The Red Sky which opened with the song Wiggle Wiggle. You’d be forgiven for thinking he was gone forever.

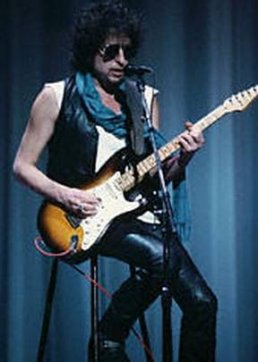

The Look: Sometimes an explosion in Cyndi Lauper’s wardrobe, at others some kind of designer leather jacket posing. Hard to pinpoint, just as his music was.

The Turning Point: The murder of John Lennon in 80, a lawsuit against his former manager Albert Grossman, death threats and the death of a close friend all within 18 months seemed to spin Dylan. He became eccentric and even more unreliable (not turning up to studio sessions), and in 88 embarked on what became known as The Never Ending Tour playing well over 100 nights a year sometimes.

Essential Listening: Oh Mercy (89); Good As I Been To You (92)

Also: In 91 Dylan released the three-CD set The Bootleg Series Vols I-III, an enlightening, chronological collection of (mostly) unreleased songs from all periods of his career. Songs Dylan didn’t release during the 80s were often vastly superior to those he did. A cornerstone in any sensible Dylan collection.

NOT DARK YET

In the late 90s Dylan was still endlessly touring, playing everything from stadiums to small community halls. In 97 he released Time Out of Mind which was immediately hailed as work of genius. It also announced the start of a golden period for Dylan, now in his 60s, as a modern day troubadour. He was still wayward -- the 03 movie Masked and Anonymous in which he plays a famous singer called Jack Fate is baffling but worth seeing for its self-referencing -- but the albums have been dark, emotionally dense, and the equal of anything in his career. He has also become a repository of thousands of old and sometimes forgotten songs.

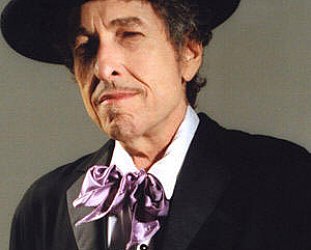

The Look: Mississippi riverboat gambler. Dapper suits, thin ties, large hats.

The Turning Point: In the early 90s it was clear Dylan had lost his way so for two albums, Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong, he went back to old folk songs which had once been the wellspring of his talent. At the time it looked like writer’s block, in retrospect he was rediscovering the weird old American music that Harry Smith had anthologised and which had inspired him 40 years before.

Essential Listening: Time Out of Mind (97), “Love and Theft” (2001) , Modern Times (06)

Also: Often described as reclusive, Dylan in the past decade had been anything but: he has given interviews (usually convoluted), done a radio show where he plays old and often obscure folk and blues, and notably in 04 finally delivered the first part of his long-promised autobiography, Chronicles. It was non-chronological and just picked pivotal periods in his career -- but it is enigmatic, elusive, allusive, and full of wit and insight.

Much like the career of the man himself.

FINALLY -- ABANDON ALL HOPE

In a long career Dylan has released many albums which it is best to avoid, among them: Self Portrait (70) which is him roaming through awful cover versions; Dylan (73) which included songs that weren’t even good enough for Self Portrait; Saved (80) from the height of his Christian period and depth of his creativity; Empire Burlesque (85) which had nice tunes and terrible production; Knocked Out Loaded (86) with only one decent song Brownsville Girl; Down in the Groove (88) which is utterly unlovable although Dylan seems attached to the song Silvio in concert even today; and the notorious Under the Red Sky (90) which was so awful even the cast of luminaries such as George Harrison, Dave Crosby, Elton John and others couldn’t save it.

Wiggle Wiggle is a laugh-out loud track however.

Live albums such as Real Live, Dylan and the Dead, and the MTV Unplugged session should come with a public health warning.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the New Zealand Herald, July '07

post a comment