Graham Reid | | 5 min read

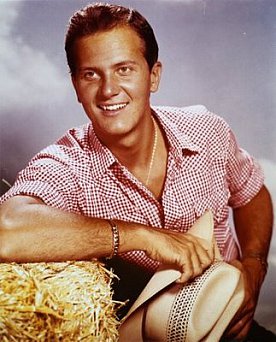

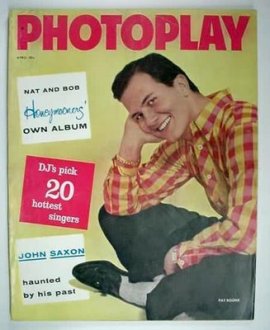

Pat Boone: Wish You Were here Buddy (1966)

If conventional wisdom and the

rock'n'roll history books are to be believed, Pat Boone was one of

the villains - simply because he was so nice.

He was the square when his

contemporaries were the sneering, hip-swinging Elvis, the outrageous

Little Richard and the adult, knowing Chuck Berry.

Boone – who turned down a film role

early in his career because he would have had to kiss a woman who

wasn’t his wife – idolised Bing Crosby and adapted raw elemental

black music into the smooth style of the Old Groaner.

Boone’s bland and palatable

popularisation of rhythm and blues meant the music -- albeit in a

very diluted form – made it into conservative Middle American homes

it otherwise wouldn’t have reached. And plenty of them. He scored

an impressive 38 top 40 hits in America in the seven years to 1962

and sold more than 46 million records.

Rock historians might not like to admit

it but Pat Boone, with April Love, Love Letters in the Sand and the

like, rivalled Elvis for a while.

Rock historians might not like to admit

it but Pat Boone, with April Love, Love Letters in the Sand and the

like, rivalled Elvis for a while.

Growing up in Jacksonville, Florida, he

“dreamed of being a singer but the chance was practically nil

because we knew no one in the business,” says this affable but

still unashamedly morally and politically conservative 60-year-old.

“My mother was a nurse, my father a

building contractor, and I took a few piano lessons. I never learned

to read music but always sang because I was always willing and

confident of my ability to carry a tune."

He sang to business, church and civic

groups and won a talent quest which took him to New York, where he

won the final and went on to another professional talent show.

His first record was a hit and in 1955

he scored a number one with a pallid version of Fats Domino’s Ain't

that a Shame.

“I had just enrolled in Columbia

University in New York City and thought I was going to be a

schoolteacher. I was going to major in English and Randy Woods of Dot

Records wanted me to sing a song called Ain't that a Shame . . .

which was not good English! I tried to sing it as ‘Isn’t that a

shame’ but it just didn't work out."

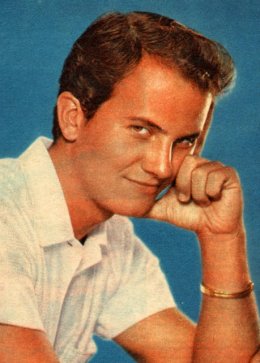

And so began a career, first in music

later in film and television, which saw Boone – with his youthful,

college-boy looks and trademark “white bucks” (shoes) -- as the

acceptable face of the emergent postwar youth culture.

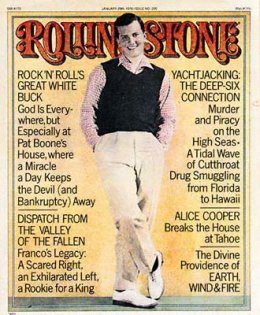

Boone today accepts he diluted

rock’n’roll to popularise it and in retrospect feels he has to

“take some of the blame or credit for helping rock'n'roll become an

accepted music form. Now that I look at where it’s gone I think

it’s more blame than credit.”

“I think some of the fears that

parents and preachers had about where rock'n'roll would take the

younger generation have become well founded, not so much then because

there was an innocence about rock 'n’ roll at the time.

"We’d clean up the lyrics - I

know I did - but the kids didn't care so much about the lyrics, they

just wanted the fun of the music. But then business people got very

much involved and found if they could encourage anarchistic

rebellious young people to write about taboo things that there would

be a lot of kids who would gravitate towards those things.

“The fellows in the ivory towers and

three-piece suits not only encouraged the writing of songs about

drugs and sex and all sorts of things but then they discovered they

could get the DJs to play them if they supplied them liberally with

drugs.

“The music business became pretty

corrupt.”

By that time, however, Boone was no

longer a force. His hits stopped coming, the Beatles arrived and a

new consciousness was abroad. Not one that he likes even today.

He understood the resentment many felt

about the Vietnam conflict but still believes civil disobedience and

burning draft cards was unacceptable.

“I think when we went into Vietnam it

was with some fairly lofty goals. We wanted to keep people from being

enslaved. We did have some economic interests there too. We never got

into an all-battle -- and it would have been an even more frightful

thing if we had, I guess.

“But I didn't agree with rebelling

against the Government, burning draft cards and all sorts of civil

disobedience.

“When I was of draft age for the

Korean War I conscientiously objected to training how to kill because

of my religious upbringing but I was willing to train to be a medic

and go on the front line and risk my life. But it would be to save

life, not take it.

"In the Sixties I wrote and

recorded Wish You Were Here, Buddy [included on this set] which was from the viewpoint of a

guy already in Vietnam in a foxhole or jungle and hearing about some

friend back home who was burning his draft card and taking part in

big demonstrations and thumbing his nose at the Government. I didn't

think that was the proper response.

“Our Government does allow us to

dissent. We don’t have to do something that we conscientiously

object to but we don’t have to bring down the Government either

just because we don’t agree with the policy.”

Today Boone says people are having to

choose their own paths and "I just hope those who choose to go a

productive way will finally -- and they do at this point -- outnumber

those who want to go, and maybe even conscientiously believe they are

right to go, in a non-constructive path.

“For instance there is a growing

number of people in America who think we were robbed when Congress

took prayer out of schools even if they wanted to have it

voluntarily. We were then flooded with drugs, guns, violence and

promiscuous sexuality and I think common sense tells you that when

there are deterrent influences you aren‘t going to have the rampant

involvement in destructive things.

“If you have kids who pray openly and

have some sort of moral reminder then the likelihood of getting

involved in things which fly in the face of that isn't nearly as

strong.”

As with Cliff Richard, Boone kept the

contract he undertook with his audience and never betrayed it.

He never claimed to be anything other than an upright, moral citizen and today – with charity work – he is still keeping his end of the bargain.

For another side of Pat Boone, the man in "a metal mood", have a listen to this.

post a comment