Graham Reid | | 5 min read

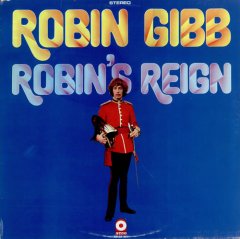

Robin Gibb: Saved by the Bell

Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees – younger

brother of Barry and twin to Maurice who died in 2003 – is on the

road again, this time singing the Bee Gees' classics as a solo

artist. And he's done it before.

Forty years ago in fact when he briefly

quit the band after their Sixties fame (half a dozen chart-topping

singles) and was enjoying a solo hit with Saved by the Bell – a

shrill, aching ballad – Robin Gibb was the drawcard at the Redwood

Music Festival just outside Auckland. He remembers it, but not

fondly.

“It was quite chaotic because there

was a whole lot of people and not a lot of security. I almost had to

climb a tree, it was frightening. It got quite dangerous. The concept

of security hadn't crept into the popular arena. It started out as

enjoyable and then the audience got out of hand.”

And someone threw a tomato at him as a

You Tube clip shows.

And someone threw a tomato at him as a

You Tube clip shows.

Gibb's orchestrated 70 solo album

Robin's Reign – which contains Saved by the Bell – is considered

a pop-psychedelic masterpiece in some circles: “Sometimes on the

BBC they'll play unreleased tracks from that album that even I

haven't got.”

However within months of that debacle

at the Redwood festival Robin was back with his brothers and the

second, even more successful, phase of the Bee Gees' career began.

The Bee Gees' story from there can be

told in prompt words and statistics: Saturday Night Fever, disco,

Grease (written by Barry), Islands in the Stream for Dolly Parton and

Kenny Rogers (which they originally wrote with Marvin Gaye in mind);

in excess of 200 million units shipped; their songs recorded by more

than 2500 artists; six consecutive number one singles in the US in 18

months from early 78 . . .

In terms of popular success their only

songwriting equals have been Lennon and McCartney, although Robin

makes a point about that comparison.

“When I'm in England, Europe, New

York, Los Angeles . . . wherever, if I turn the radio on I hear about

four or five Bee Gees or Gibb brothers songs every day, but not the

Beatles . . . and it's because our music has got black influences to

it. People of a younger generation can relate to it, whereas the

Beatles music is very fixed in its time, the psychedelic music of the

late 60s doesn't quite gel.

“Stayin' Alive doesn't sound out of

place, but Strawberry Fields would.”

The Bee Gees have always recoiled from

the word “disco” but Robin seems no less comfortable with the

suggestion the continued success of many of their songs is that they

are dance-driven.

“You say that, but we didn't think

when we were writing any of our music that you would dance to it. We

always thought we were writing r'n'b grooves, what they called

blue-eyed soul.

“So we never heard the word 'disco',

we just wrote groove songs we could harmonize strongly to, and with

great melodies. The fact you could dance to them, we never thought

about.”

He is insistent however that what got

them into the top echelon of legendary songwriters and performers was

hard work, and the ability to play live. They'd been doing it since they were kids.

He is insistent however that what got

them into the top echelon of legendary songwriters and performers was

hard work, and the ability to play live. They'd been doing it since they were kids.

“We are actually one of the acts that

could sing real all the time, and that was considered normal. If you

sing live on stage today that's considered abnormal.

“People ask me about starting out and

say it was easier then. But it was harder because a record company

wouldn't sign you unless you could play live and carry a show.

“The benchmark for getting a

recording contract was much higher. Today people have [expensive]

recording equipment in their front room -- but it doesn't make them

songwriters or great singers or harmonizers. What it can do is make

pretty bad songs sound good, for a while.

“For not very talented, professional

or seasoned young bands it's possible to bring out a record and get

immediate recognition for a groove or a sound they otherwise couldn't

get if they hadn't had access to this advanced technology.”

He also says British acts today aren't

as hungry to break into America as those of his generation: “So

very big acts mean nothing beyond the White Cliffs of Dover. In the

past the whole of the American market would open up because they went

over there and worked their guts off, as we did. A lot of young

artists in the UK just don't put time into it. They want it, but you

can't get the States and still live in London.”

Yet if anyone thinks he – at age 60

and feeling fine after a recent health scare – can just coast on

past glories he puts them straight: yes, there is the four CD

retrospective Mythology box set coming in November at the same time

as a film of their lives, but he and his son Robin-John are currently

writing The Titanic Requiem to be recorded by the Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra in advance of the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the

Titanic in 2012 (“it's very traditional, not a rock opera, there's

no backbeat”), and he and Barry still get together when the mood

and ideas take them.

“We're cherry picking. Barry and I

just do what we want to do and now are concentrate on the film of our

life story. We came together for the last American Idol show in May

in Los Angeles, and the Rock And Roll of Fame in March [where they

inducted Abba].”

And he has been re-elected as the

president of the International Confederation of Authors and Composers

which defends copyright, something he feels strongly about. Always

useful to have good lawyers?

“Of course, that's a given,” he

laughs.

But it has always been about building a

song catalogue.

“Because we've been composers, the music has gone ahead of us. It's always on the radio and although technically you may not be out there as the Bee Gees, you go past the pub and there's a Bee Gees tribute band. People are queuing up to see someone who gets up in the morning and makes a living out of being me. Astounding.”

Robin Gibb died in May 2012. He was 62.

post a comment