Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Badfinger: Day After Day

There are two stories every young musician should read, the first is obvious. The Beatles story is full of magic and coincidence; McCartney's meeting with a drunk Lennon, Harrison getting in by playing Raunchy to them while on a bus, the Hamburg days and the death of Stu Sutcliffe, the firing of Pete Best and Ringo entering just before they went into the studio, the touring and madness, the drugs . . .

And of course the ever-evolving music.

The

other story is when the dream goes sour, as happened to the

Beatles-anointed power pop band Badfinger whose music has rarely been

given its due.

Perhaps

that's because clouds of sadness – nasty management, two suicides,

the band impoverished – hang over them.

Yet

it all started so well.

Brought

to the Beatles' Apple label in early '68 by Mal Evans – the

Beatles' roadie – they were originally called The Iveys. In July

they were signed, after a couple of good but mostly unsuccessful

originals they changed their name and McCartney gifted them his song

Come and Get It

on the condition they record it exactly as he said.

They

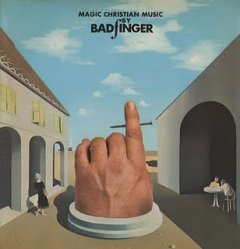

did, it was hit and their debut album was Magic

Christian Music -- although confusingly Come and

Get It appeared in the

Peter Sellers/Ringo film Magic

Christian so there was

the Magic Christian

soundtrack out simultaneously.

They

did, it was hit and their debut album was Magic

Christian Music -- although confusingly Come and

Get It appeared in the

Peter Sellers/Ringo film Magic

Christian so there was

the Magic Christian

soundtrack out simultaneously.

It wouldn't be the first time there was confusion in the marketplace over Badfinger. It was something of a harbinger.

But in those golden days they played on Lennon, Starr and

Harrison singles or albums, and joined Harrison on-stage at his

Concert for Bangladesh.

Within

their ranks they had two terrific songwriters, Pete Ham and Tom

Evans, and together they crafted sterling power pop which owed a nod

to the Beatles but was much more driving. They were like the Big Star

of Britain – Cheap Trick would later adopt their pumped-up pop

style – and they enjoyed a number of hits, not the least their

originals No Matter

What and the

Harrison-produced Day

After Day. Harry

Nilsson took their Without

You to the charts.

It

looked like they had been touched by Midas – but they hadn't

counted on their manager, the American Stan Polley, draining their money

away, the constant Beatles comparisons, some line-up changes, then a

switch to Warners. And as a result two albums arriving almost

simultaneously, Apple's Ass

and Warners' Badfinger.

Reviewers and the public were baffled.

Despite

setbacks they delivered cracking albums – and Magic

Christian Music, No Dice

('70), Straight Up

(71) and Ass

(73) from their peak on Apple have been remastered (by those behind the Beatles remastering and McCartney remastering) and are reissued with extra tracks, and each has a booklet which tells the story of the album and the band in that period.

Ironically

-- despite dropping their name The Iveys (“People kept asking us if

were the old Ivy League,” said Pete Ham) – for Magic Christian

Music, every track was recorded when they still had the old name.

The

new Badfinger name – and repositioning of themselves – came from

the title an unrecorded Lennon (or McCartney, depending on which

version you believe) piano piece Bad Finger Boogie which eventually

(and ironically in their case) became With a Little Help From My

Friends.

The tracks on Magic Christian Music -- aside from Come and Get It and two others written for the film -- were pulled together from the most commercial things they had already recorded.

One of them, the

throwaway Give It A Try, had been prompted by Apple knocking back

songs the band felt were potential singles.

And

so began a trend of writing about matters close to their heart.

Badfinger were more autobiographical than many at the time might have

thought.

Magic Christian Music has its moments (some of it a bit McCartney circa 1970, of course) but you can't help be impressed by their musicianship – excellent acoustic playing, great power rock guitars which were kicked up a notch from the Iveys – however the songs really weren't there or stood too squarely in the shadow of their mentors.

Aside from the cracking Come And Get It; the gorgeous, orchestrated pop of the wistful Beautiful and Blue; and the gentle Dear Angie (written by Ron Griffin, the Iveys bassist who was dumped -- Pete Best-like -- before the name change), the songs suffer from being a bit lightweight.

But look at the help they had: Tony Visconti produced a few tracks and arranged the strings on Evans' Maybe Tomorrow (an Iveys hit), and George Martin arranged the strings on the pastoral Carry On Until Tomorrow.

The reissue adds five other tracks, among them the six minute psychedelic track I've Been Waiting from their Iveys days.

But

they really stepped up for No Dice, which we might say was the first

real Badfinger album. It included their Mal Evans-produced killer single No Matter What (#5 in the UK, #8 in the US) and was the best-selling album of their career.

But

they really stepped up for No Dice, which we might say was the first

real Badfinger album. It included their Mal Evans-produced killer single No Matter What (#5 in the UK, #8 in the US) and was the best-selling album of their career.

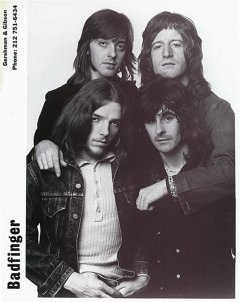

The arrival of guitarist Joey Molland alongside Ham, Evans and drummer Mike Gibbins was the classic line-up, and No Dice was mostly produced by former Beatles-engineer Geoff Emerick in his first major production role.

The album bristles with rock and power pop (one of the more straight-up rockers is entitled Love Me Do), every member of the band is attributed in the song credits, material like Midnight Caller sounded like the best McCartney was offering at the time and it contains their version of Without You, a song pieced together from two separate pieces Ham and Evans had written separately.

And Ham's We're For the Dark is a lost classic for its acoustic psychedelia and orchestration. (The extra tracks on the reissue include demos of Without You and No Matter What.)

Rolling Stone said, "With their new album No Dice, Badfinger has to their credit one of the best records of the year". And it was released into a world which had massive albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Lennon (his Plastic Ono Band album) and Harrison (All Things Must Pass).

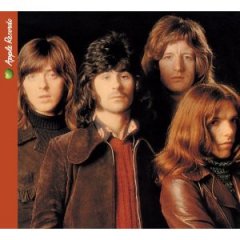

The following album Straight

Up -- in a cover (left) which invited the comment "Badfinger For Sale", the inescapable Beatle reference -- didn't come easy.

The following album Straight

Up -- in a cover (left) which invited the comment "Badfinger For Sale", the inescapable Beatle reference -- didn't come easy.

Harrison had shown interest in producing but the band had already recorded a dozen songs with Emerick. Harrison was taken with the song Name of the Game which he thought could be a big single and tried a couple remixes, one by Al Kooper and the other a Harrison-Phil Spector effort. But neither of these worked out -- and nor did the album.

Apple rejected the Emerick sessions, or more correctly Harrison did, and Harrison then signed up to make a more slick album (along the lines of Abbey Road). The material was certainly strong and songs like Baby Blue, Day After Day and Sweet Tuesday Morning are among Badfinger's finest songs.

Then Harrison was off to further the Bangladesh cause and a third producer -- improbably Todd Rundgren -- was signed who applied himself and finished the material which had been left hanging after Harrison's departure.

Despite the summery sound of most songs the lyrics are, in many places, dark or troubled: Evan's Money reflected not just the greater economic climate but their own lack of the readies; some of Ham's songs deal with complex relationships with women he was having; and Flying (yet another titled shared with the Beatles) has a cynical, negative bent.

Just as the Beatles had been world-weary by the time of Beatle For Sale, so too Badfinger were finding the constant touring a drain on their energies, even if the strong songs here didn't reflect that.

But it was an album born out of trying and obviously frustrating times. Take It All reflect on "in a way, the sun has shone on me", which could be a reference to Harrison (and his Here Comes the Sun). I'd Die Babe, which was a particular favourite of Harrison's, sounds like Lennon and Harrison had dropped in on McCartney's Band on the Run sessions.

Reviews cited the Beatles' connection very favourably, Day After Day topped the Cashbox charts and the success of Nilsson's version of Without You was encouraging. But in the world of their management things were going haywire: Stan Polley's accounts show that for the year to Oct 1971 band members averaged around $6000 in salaries and advances, Polley himslef took a commission of almost $78,000.

Around this time they realised Apple wasn't working for them and were courted by Warners.

Around this time they realised Apple wasn't working for them and were courted by Warners.

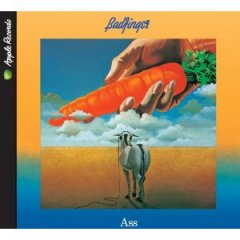

Their final Apple album was Ass, which opens with Apple of My Eye: "I'm sorry but it's time to make a stand, though we never meant to bite the loving hand and now the time has come to walk alone, we were the children, now we've overgrown . . ."

The chaotic Apple label was being wound down and Badfingers' Apple of My Eye was the last non-Beatle single it released.

Ass is the sound of a band toughening up, both in lyrical confidence and its music, despite two of the songs -- The Winner and I Can Love You -- coming from the Rundgren sessions of two years previous.

The producer for these sessions was Chris Thomas (who's done Beatles work too) but the album was their last flourish on Apple and they were actually at Warners by the time it came out to mixed reviews.

This is almost where their story ends: their Warner debut simply entitled Badfinger (they'd wanted For Love or Money, another harbinger) was a return to pre-Ass sound but arrived as Ass was hitting stores, the business deals with Polley (the invisible man) got worse, and then Ham committed suicide in April '75 leaving a note which in part read “Stan Polley is a soulless bastard. I will take him with me.”

Ham had just turned 28 and was

broke. His daughter was born a month later.

Badfinger

limped on but in '83 Evans killed himself – after yet another

dispute over royalties with Joey Molland -- in exactly the

same way.

Badfinger

limped on but in '83 Evans killed himself – after yet another

dispute over royalties with Joey Molland -- in exactly the

same way.

Badfinger were a pop band who never became pop stars, said Dan Matovina who wrote their biography Without You; The Tragic Story of Badfinger in 97.

But their vibrant, often nakedly autobiographical, pop-rock

still sounds fresh.

In

many ways Badfinger were a band that didn't

ever get their real due, but was acknowledged after their lifetime.

Yet

it all started so well.

They

had an in-joke about their career of golden promise and repeated

blows: read their album titles after Magic

Christian Music.

The

cover of Ass

– Evans' idea – is of a donkey in headphones being lead on by a

huge hand from the heavens holding a carrot. It captures how they

felt about Apple.

Tragic story, glorious music . . . and a lesson, with a great power pop soundtrack, for any young musician about to sign a contract.

Interested in more along these lines? Then check out this.

post a comment