Graham Reid | | 7 min read

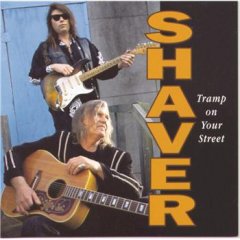

Billy Joe Shaver: When the Fallen Angels Fly (1993)

The truth about Billy Joe Shaver is

much more interesting than anything anyone might make up about the

guy. Shaver has lived on the hard edge of life.

Born in Corsicana in Texas in late 1941

or '39 depending on where you read it (“just a cotton-gin town, the

same one Lefty Frizzell came from") and raised in Waco, he lost

two fingers in a sawmill accident when he was 26 ("the Lord was

telling me somethin' “), was married three times -- to the

same woman Brenda (“she's an idiot, she kept accepting so that makes her

dumber than me") and considers himself a Christian (“but I'm

still a sinner," he laughs in a creaky voice).

Shaver is also one of the finest

contemporary songwriters whose lyrics reflect the scuffs of life. His

country style with a tough blues input has drawn favourable

comparisons with Hank Williams and his songs have been recorded by

Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and most other country singers in

search of an authentic lyric.

Shaver is also one of the finest

contemporary songwriters whose lyrics reflect the scuffs of life. His

country style with a tough blues input has drawn favourable

comparisons with Hank Williams and his songs have been recorded by

Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and most other country singers in

search of an authentic lyric.

And in the early Nineties Shaver didn't

have a recording contract of his own.

"Yeah, Columbia dropped me,"

he told me at the time. “I didn’t bounce so good this time so I just

went off and wrote a few songs and came out fightin' again."

Being dropped by a record company is no

big deal. Shaver has seen worse times.

He was raised by his grandmother and by

his own account they barely survived. Even when times got good and

his grandmother got a radio they “still had to pinch pennies so I

didn't get to listen to it except at certain times."

He started singing at age five and

"down at the general store they'd extend credit on my

grandmothers bill if I'd sing. They'd stand me up on a crackerbarrel

and I'd sing just whatever I could remember from off peoples radios.

I’d make up the bits I couldn't remember."

When Shaver was 12 his grandmother died and he moved closer to his mother who “was a honky-tonk gal and ran a place called The Green Gables with another gal named Blanche. To tell you the truth I grew up in those places. They were kinda rough but I didn't notice that at the time.”

It was experiences in such places that

gave Shaver the impetus later to pen Honky Tonk Heroes, the song

Waylon Jennings chose as the title track of his '73 album which

featured all but one tune written by Shaver. (Another song off it

co-written with Jennings, You Ask Me To, was later recorded by Elvis

Presley.)

And Shaver says a memorable incident

one night as a child also gave his life direction.

“I heard Homer and Jethro and the

Light Crust Doughboys were playing at the Wonderbread factory so I

snuck out the house and walked the five miles down the railroad track

to see them. They let me in for free 'cause I was barefoot and looked

kinda pitiful, I guess.

“Because the county was dry all the

bootleggers came along and got everyone half-lit, then some guy came

on and said, 'Here's a new guy y'all don't know -- but you soon will'

and they brought on Hank Williams.

“Nobody paid much attention to his two songs but he looked me right in the eye and sang them to me. I got so moved by that I decided that’s what I wanted to be from then on, so I started writing -- but it was considered a bit sissy."

It also took a lot of strange turns in

his life before he was writing in a way which satisfied him. A few

years in the navy, some time as a cattle puncher and then the period

in the sawmill which lead to the accident.

“A chain pulled a couple of my

fingers off and I nearly lost my arm. I realised then I wasn‘t

doing what I was supposed to do. So I went to Nashville in '66 but it

was hard getting in because you had to be good and the older

songwriters had a lock on everything.

“I worked for Bobby Bare's publishing

company and got paid $50 a week. But the cheque would sometimes

bounce – Bobby was in as bad a shape I was."

The job meant turning in a couple of

songs a week and early on he met Waylon Jennings. It wasn’t exactly

overnight success but Shaver songs started getting attention.

In rapid succession his songs were

covered by Kris Kristofferson (who did Good Christian Soldier and

later produced Shaver's debut album Old Five and Dimers Like Me in

'73), Tom T. Hall, Jerry Reed, Tex Ritter, Johnny Rodriguez and John

Anderson ("He just about wore out l'm Just an Old Chunk of

Coal").

“I guess I knew I'd sort of ‘made

it' as a song writer when Bobby Bare did Ride Me Down Easy because

that song was so close to me I didn’t even recognise it could

become a hit. It was about me and I didn't think anyone else would be

interested."

But increasingly people did become

interested in Shaver-penned tunes. His songs are sometimes

controversial in country circles: Black Rose was about an interracial

relationship and contained the lines “the Devil made me do it the

first time, the second time I done it on my own”.

He fell victim of drink and drugs to

the point of failing to record an album for MGM, hated live

performances in the Seventies, had songs written about him by Kris Kristofferson (The Fighter) and Tom T. Hall (Joe, Don't Let The Music

Kill You) and wrote about Willie Nelson in Willie the Wandering Gypsy

and me. In the late Seventies he turned to religion.

With only six albums in his first 20

years, he was often passed over by mainstream country audiences at a

time when there were maybe too many “outlaw” artists, but Shaver

was the real deal and his earthy lyrics have made him a champion in

the eyes of working people.

"A lot of country singers have

been doing it since they were kids and that’s been very much all

they did. I worked right up until my accident and even after I messed

my fingers up I was still working. I fell off a house when I was

building and broke my back. I think the Lord had a message for me but

I‘m kinda dumb and took a long time to catch on.”

These days Shaver is very much a

full-time singer/songwriter although he has appeared in a few films

(among them The Apostle of the mid Nineties opposite Robert Duvall)

but albums remained infrequent until the 2000s, not just because he

was “between labels" but he admits he lives with his songs for

a long time before recording.

And he has a wry sense of humour which

has no trace of bitterness despite sometimes being on the losing end

of life.

Of a trip to London to perform at a big

festival in the early Nineties ("my first time over the water to

tell you the truth") he laughs in his slow, cracked voice at the

cost of taking a band over, only to find no cheque forthcoming from

the promoters: “Those dirty dawgs, the guy‘s name was Mervyn, we

call him swervin` Mervyn, the rascal."

In '99 both his wife and mother died,

the following year his 38-year old guitarist son Eddy (left) with whom he

toured and recorded died of a heroin overdose, and the following year

he had a heart attack and nearly died on stage in Texas. In 2006 he

was inducted into the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame and he served

as spiritual advisor to Kinky Friedman in his run for state governor.

In '99 both his wife and mother died,

the following year his 38-year old guitarist son Eddy (left) with whom he

toured and recorded died of a heroin overdose, and the following year

he had a heart attack and nearly died on stage in Texas. In 2006 he

was inducted into the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame and he served

as spiritual advisor to Kinky Friedman in his run for state governor.

In the late 2000s there was an incident

involving a gun in bar (he shot a man in the face after a

disagreement) but was acquitted when his claim of self-defense was

accepted.

Shaver is one of those unique, genuine

country artists a long way removed from the sanitised artists who

appear on television screens from time to time. His songs have been

covered by rock musicians (the Allman Brothers did Sweet Mama),

Presley, Dotty West, Jerry Jeff Walker and, when the outlaw country

movement was at its height, Waylon, Willie and the rest.

But to hear the man sing his own songs

is a rare treat “because it all starts with a song."

“Songs come real easy, for me this is

still a hobby. I never did it for the money because I could always

make more breakin' in horses. But I love this and still do.

“I just record my stuff and if

someone else wants to do them l usually find out later. I don't push

my songs to anyone. I'd have a hard time doin' that. It would be like

sellin' a kid."

post a comment