Graham Reid | | 7 min read

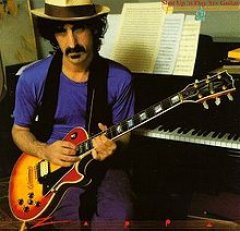

Frank Zappa: Ship Ahoy (from Shut Up 'N Play Your Guitar)

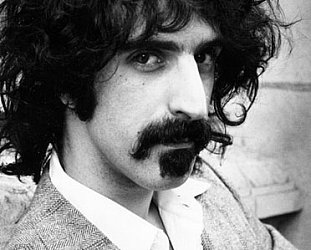

The irritation, pleasure and difficulty

with Frank Zappa was that he was always part of rock culture - but

not exactly a rock musician. Well, not when it suits him.

“Being a rock star is nothing to

aspire to," he once said. “Rock stars have to be cute and I`m

a realistic guy. I shave this face every day. I know the deficit I’ve

got."

But as the always-quotable Zappa (“the

stuff I do has a low mindless-fun quotient”) also noted, he didn’t

write a rock song until he was 20. Up until then all he’d ever

written was chamber music and orchestral pieces.

"I couldn’t get them performed

and the only way to hear them was to hire people ... and that’s

what I’ve been doing all these years. Hiring people to play. Some

hobby, huh?"

That "hobby" stretched over

40 years and Zappa (“I don't care about being middle-aged, I care

about music”) was still irritating and confounding into his late

Fifties. That's some achievement in itself, but eventually you have

to come back to his enormous, sometimes extraordinary, often

indifferent body of work.

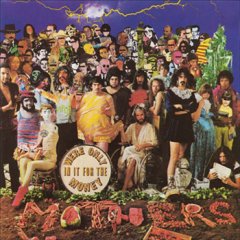

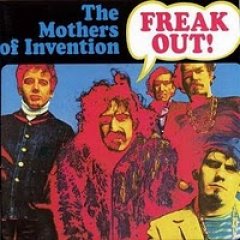

Over 40 albums by Zappa (“I like

tobacco") are readily available and they date back to his first

three seminal albums Freak Out, Absolutely Free and his cruelly

incisive parody of Sgt Pepper's and hippies, the sprawling but astute

and pointed We’re Only In it For The Money.

Over 40 albums by Zappa (“I like

tobacco") are readily available and they date back to his first

three seminal albums Freak Out, Absolutely Free and his cruelly

incisive parody of Sgt Pepper's and hippies, the sprawling but astute

and pointed We’re Only In it For The Money.

Few records in rock culture stand up to

serious scrutiny after more than four decades and Freak Out perhaps

sounds more tame today than it was at the time. It’s still very

odd, however.

Like all his early albums, Freak Out is

a sound and style collage which swerves from the paranoia-persecution

of Who Are The Brain Police? (picked up by Cheap Trick two decades

later for Dream Police) to Go Cry, a sleazy doo-wop number which

anticipated Zappa’s '68 album Reuben and the Jets, a loving

recreation of Fifties wop-pop.

With hindsight it is clear just how

much an album of its period Freak Out! was, although when lined up

against its contemporaries like the Beatles’ Rubber Soul and the

Stones’ Aftermath, it sounds bizarre.

Zappa's rock vision, such as it was,

seemed moulded by the late Fifties and his attempts at creating a

Sixties pop-rock sound could swerve uncannily close to American pop

bands like the Turtles. It was little surprise, therefore, when

ex-Turtles Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman (who styled themselves Flo

and Eddie) joined Zappa in '71 around the time of his 200 Motels film

and album. (Lousy film, good soundtrack was the unanimous verdict).

The movie pointed up the problem which

plagued Zappa and infuriated those who liked some stuff but were

bored witless by most of his output. The film, like so many of his

records, was unfocused. Weirdness is fine but Zappa (“I never set

out to be weird, other people called me that”) was too often weird

with little purpose.

The albums of early work which stand up

the best today are therefore those breakthroughs in the Sixties –

Freak Out!, his orchestral album Lumpy Gravy, We're Only In It For

the Money and Uncle Meat – where he denied any musical or social

parameters: blistering guitar solos, spoken word, cut-ups and

dialogue, orchestral passages, satire, low-brow humour, high flying

ideas . . . . They were all there, sometimes on the same album.

The albums of early work which stand up

the best today are therefore those breakthroughs in the Sixties –

Freak Out!, his orchestral album Lumpy Gravy, We're Only In It For

the Money and Uncle Meat – where he denied any musical or social

parameters: blistering guitar solos, spoken word, cut-ups and

dialogue, orchestral passages, satire, low-brow humour, high flying

ideas . . . . They were all there, sometimes on the same album.

Within three years, Zappa had outlined

in broad and sometimes crude strokes, his musical agenda. After that

there was refinement, expansion, retrenchment . . .

He announced himself as someone apart

from the rock culture in which he found himself. Parodying the Sgt

Peppers artwork and conceptual style, We’re Only In It mercilessly

satirised hippie culture (“Mmm, my hairs getting good in the back”)

yet also contains some of Zappa's most affecting songs, like Mom and

Dad, which addressed “The Generation Gap,” an issue of some

importance to white middle-class, Time magazine-reading parents

worried about this peace, pot and love beads explosion in San

Francisco.

He announced himself as someone apart

from the rock culture in which he found himself. Parodying the Sgt

Peppers artwork and conceptual style, We’re Only In It mercilessly

satirised hippie culture (“Mmm, my hairs getting good in the back”)

yet also contains some of Zappa's most affecting songs, like Mom and

Dad, which addressed “The Generation Gap,” an issue of some

importance to white middle-class, Time magazine-reading parents

worried about this peace, pot and love beads explosion in San

Francisco.

Zappa (“I'm interested in finding out what can be done with different forms of musical expression -- without any interference”) despised hippies, held agencies of control in contempt and always liked nothing better than to work.

A libertarian with long hair and a

belief in the family unit.

Zappa ("I am a devout capitalist

and always have been”) was the drug-free freak who looked like a

hippie yet fervently spoke against the "tune-in. turn-on and

drop-out" ethic.

That made you as useless as The

Establishment, he argued, and on the cover of Freak Out -- the first

double album in rock culture -- he wrote "forget about the

senior prom and go to the library and educate yourself, if you've got

the guts.”

Zappa ("If I want to wear a dress,

that’s my business") was always hard to figure but basically

he stood for an intellectual, rational and reactionary change of

consciousness.

Suspect everybody, work at your work

and beat ‘em at their own game -- weirdly, if possible.

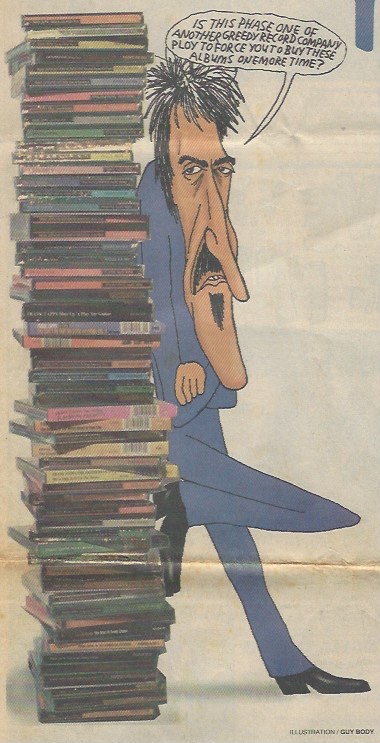

The big drawback with Zappa (“daylight

is an ugly time of day”) has always been he made too many

indifferent albums littered with tedious and juvenile underwear and

toilet jokes then claimed socio-political significance for them.

He may have whinged that he wasn't

taken seriously enough -- but that’s hardly the listeners' fault.

He may have whinged that he wasn't

taken seriously enough -- but that’s hardly the listeners' fault.

Albums like the Shut Up 'N Play Your

Guitar (an exquisite, fluid triple album/double CD of live and studio

guitar work) confirmed he was a master on the instrument, just as the

’84 Boulez Conducts Zappa showed that he was the serious composer

he always claimed to be – even though Pierre Boulez only conducted

three of the pieces and the other four were by Zappa himself. But

context was everything.

But there were too few examples (and

too many albums) like those in a career which produced more than 60

albums in his lifetime (another 20 or so since his death in December

'93). And were not counting the numerous bootlegs.

However, rock culture would be the

poorer without Freak Out, Absolutely Free, We’re Only In It For The

Money, Hot Rats and others.

But in his lifetime Zappa (“I’m

biologically disposed to Bulgarian folk music") was neither as

funny nor as significant as he -- and his devotees – thought. He's

irrelevant, said Bob Geldof when I spoke to him in the early

Nineties, just a man who has cynically exploited himself.

Not that such criticisms have ever

worried Zappa, of course. As far back as Freak Out he noted how

“everybody worries so much about not getting airplay . . . my, my."

He said he didn’t need anyone to pat

him on the head when he did good. In fact, he said he couldn’t care

less what A people thought. Or words to that effect.

Since his death there have been the

inevitable re-evaluations because his output meant you had barely

dealt with one album than another – often very different –

artifact arrived.

With time to consider that massive

catalogue other albums stand out: the live Roxy and Elsewhere of '74;

the sprawling and demanding Joe's Garage rock/mock opera; selective

pickings through his series You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, and

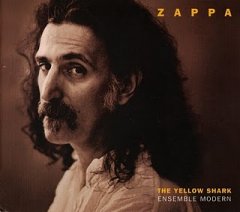

his final album The Yellow Shark which confirmed his place as a

contemporary composer who free-wheeled through blues and classical,

fusion and low humour.

With time to consider that massive

catalogue other albums stand out: the live Roxy and Elsewhere of '74;

the sprawling and demanding Joe's Garage rock/mock opera; selective

pickings through his series You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, and

his final album The Yellow Shark which confirmed his place as a

contemporary composer who free-wheeled through blues and classical,

fusion and low humour.

Frank Zappa has been gone close to 20

years now but people still listen to his work, essay and analyse it –

and through the agency of his wife, it just keeps coming.

Like him or not, it looks like we're

stuck with him.

Welcome to the Terrordome.

There is much more on Frank Zappa at Elsewhere starting here.

post a comment