Graham Reid | | 7 min read

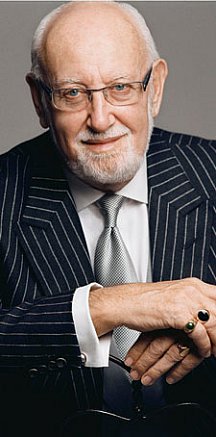

The most powerful man in jazz sits in his office six floors above Fifth Avenue, New York. He's smiling. Business is good.

Bruce Lundvall -- who began his career at Columbia Records with a hip young Miles Davis -- has been heading the famous Blue Note jazz label for 20 years. And recently business just got better. Why? In a word, “Norah".

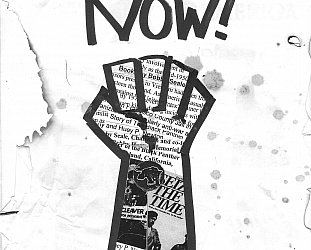

Founded by Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff in the late 40s Blue Note, the most recognised jazz label in the world, set a standard for recording quality (with producer Rudi Van Gelder) and albums in eye-catching cover art thanks to designer Reid Miles.

By the mid 50s Blue Note albums were already iconic. The extensive catalogue included some of jazz's greatest albums and most creative players. Then it withered away.

When Lion retired in the 67 the company stumbled and by the late 70s the once-proud label was moribund. But when Lundvall took over with the brief of resurrecting it and starting a parallel pop label, Manhattan, things picked up at a pace.

Today Blue Note is the market leader in jazz again. Universal offers small competition with its Verve label, but at Sony -- formerly Columbia where Lundvall cut his teeth in 1960 and left 22 years later as president -- they have all but abandoned jazz. Warners has pushed their few remaining artists onto the Nonesuch speciality imprint, and RCA has a reissue label, Bluebird.

That makes Blue Note the biggest, and Lundvall the kingpin.

Outside his office is a wall-filling photo of the label's star and money-spinner: Norah Jones.

But in Lundvall's crisply efficient and surprisingly small office are paintings and photographs of those artists with whom he has worked and called friends, Miles Davis among them.

Lundvall is immaculately groomed, dapper and comfortably chatty. He jokes about the late Art Blakey -- who complained about the new generation, ``they don't drink, they don't smoke, they just go home and ring their momma'' -- and enjoys telling how he signed Wynton Marsalis to CBS and has now signed him again at Blue Note.

Lundvall knows this music intimately and genuinely cares. He's been in it for the long haul -- and that's where he sees problems when discussing the industry today.

``There is too much focus on non-career artists, too much flavour of the minute, too much focus on things that don't have musical substance, and on artists who don't have the potential of being career artists and building a catalogue.

``When I was at CBS I could look across our rosters from Johnny Mathis signed in 1955, to Dylan to Springsteen, to Barbra Streisand signed in 63 to Earth, Wind and Fire to Chicago ... In each area of music -- in jazz Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Weather Report, Return to Forever -- these were the definitive artists. In country we had Willie Nelson.

``Sure we had one-off hits and novelties, but the focus was on artists of substance, it didn't matter what field.

``I don't see so much of that today. It takes a long time to build those rosters but once you do the legacy you can draw upon with catalogue is amazing. At Blue Note we have the legacy of Alfred Lion.

``The idea is always to keep the focus on the music and the artists, and stay away from marketing confections. There hasn't been that focus in the industry recently.''

Lundvall knows the value of back-catalogue. Half Blue Note's turnover comes from reissues, and when he spent two years between Sony and Blue Note as president at Elektra -- where he started the Elektra-Musician jazz label -- he undertook an extensive reissue programme from their vaults.

Because of that his arrival at Blue Note wasn't greeted with universal approval in jazz. Some felt he had an ear on the past, but no track record of signing new artists.

Within a few years he was proving his critics wrong, although he admits some of it was luck. He'd signed singer Bobby McFerrin to Elektra-Musician and picked him up for Blue Note. Immediately McFerrin delivered that irritating but hugely successful single Don't Worry Be Happy for their Manhattan imprint.

"Actually the first artist I signed was [guitarist] Stanley Jordan and he sold half a million copies of his debut album. I signed back to Blue Note some of its original artists like McCoy Tyner, Stanley Turrentine and Tony Williams who were still performing well, and then pianist Michael Petrucciani who was very successful.''

Where Blue Note under Lion was a label for instrumentalists Lundvall looked to vocalists, signing Dianne Reeves in 87. Then he got Cassandra Wilson who -- like Kurt Elling and Norah Jones in different ways -- has redefined how people perceive jazz. She also sold records.

The label also got lucky with the first US3 album Hand on the Torch in 93 (remixes of classic Blue Note tracks), and the first St Germain album Tourist. Each took jazz to new, young audiences frequenting dance clubs and chillout rooms, not traditional jazz venues.

The label's biggest success -- 18 million copies of her debut Come Away With Me sold worldwide, around 10 million so far of the follow-up Feels Like Home -- is the attractive young woman whose poster dominates the lobby: Norah Jones.

``She was signed as a jazz artist then decided what she wanted to do on the record,'' he laughs, admitting he was stunned by sales on Come Away With Me.

He'd heard a three song demo and watched her play a set of dozens of jazz standards and pop tunes, and knew she was special. He signed her then allowed her -- with producer Arif Mardin, a 73-year old industry veteran -- to make the album she wanted.

``Some people say she's not really a jazz artist, but she is. She swings, and one day she may make an album of standards.''

Again he admits to some luck. EMI, Blue Note's parent company, had an annual convention in Rome.

``I played the demo by Norah and showed one slide of her at the end. The place went into a standing ovation -- for a demo -- and people wanted to know who she was. It might have been the contrast between all the rock'n'roll and rap, I accept that, but people wanted a copy.

``Our chairman made a wrap-up speech in which he said we'd heard a lot of great music that week but his favourite was Norah Jones. That sent a clear signal to the company internationally.''

Jones has been under-marketed at her request. She could play on her looks but doesn't -- the media works with a handful of supplied photos -- and she even rang Lundvall to ask him to stop promoting her debut album when sales started to spiral skywards.

``She is quite shy and doesn't want to be marketed like a commodity, she wants a long-term career. But you couldn't stop it. The second album spent six weeks in a row at number one in the States.

“I can't expect it to sell like the first album, how could anything? But it's still selling. The real question will be the third album.''

Jones' sales are phenomenal in the jazz world where the average straight-ahead vocal album would do well to sell 50,000 over its lifespan. But then again, with a little country in the mix, Jones isn’t a straight-ahead jazz vocalist.

Lundvall produces a seven track sampler of an artist he holds great hope for, Amos Lee. If jazz purists recoiled at Jones being on the famous Blue Note label they will be even less happy with this snappy, slightly funky singer-songwriter from Philadelphia who has his roots in soul, folk and r’n’b.

Lee’s debut album All My Friends includes Jones as a guest on a couple of tracks, Jones’ partner/bassist Lee Alexander, her guitarist Adam Levy and acoustic guitarist Kevin Brett. If Jones’ albums sit at the intersection of gentle jazz and alt.country then Lee’s album works a more soulful folk-rock end of the spectrum, but is bound to appeal to Jones’ followers.

With Lee’s album it is as if Blue Note and Lundvall have found a niche in the adult contemporary market via Jones and are now carefully looking to fill, but not exploit, it. Lee’s album has been a year in the making and such careful nurturing of artists has been Lundvall’s way. As he says, a record company and an artist should be in for the long haul, not just the one-off success.

Some Blue Note albums don't make a profit but Lundvall says you can't be concerned if you have a quality artist. Wynton Marsalis, the man responsible for the high profile of jazz in the 80s and 90s, was selling nothing when he left Sony, largely because he had released too many albums.

``But he knows that, so we are going at it cautiously with him too.''

So for Blue Note -- which has made a profit every year, even without Jones -- things are good. Its diverse roster has newer names like vocalists Elling and Jones alongside mid-career artists such as saxophonist Joe Lovano and Cassandra Wilson, and there’s that massive back-catalogue Lion built up.

``In the current climate sales are tapering off. You stick with it because these people are a delight to work with and are really about the music. As opposed to pop artists, they've devoted their entire lives to an art form that may not make them wealthy.

``But they still do it. And as long as they do, we will too.''

This interview first appeared in the New Zealand Herald in early 2005 when Norah Jones was about to tour New Zealand.

Footnote: Bruce Lundvall died in May 2015

post a comment