Graham Reid | | 8 min read

In an airless room backstage at the Brisbane Entertainment Centre after the concert, Australian promoter and entrepreneur Michael Gudinski is buzzing.

"Wasn't that bloody fantastic?" he says to no one in particular. "I want that set list," and he reaches for his phone. Minutes later a guy appears at the door with it. Gudinski scans the 20 or so songs then says, "Only two I didn't know."

All the rest were hits. Big hits, identifiable from the first few bars.

An hour before the show, the man responsible for thrilling Gudinski -- and the capacity audience of more than 8000 -- is chatting easily backstage while his wife Julie and kids hang around.

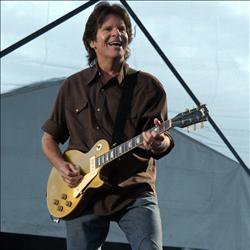

John Fogerty, the singer, songwriter and guitarist who defined the distinctive sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival in the late 60s, is short, slight and trim. At 60, with a full head of what looks like his own hair and maybe just a little work, he could pass for much younger.

In fact when he bounds on stage later he reminds me of no one more than Michael J Fox from the first Back to the Future flick: all energy, cheekbones and boyish enthusiasm.

Fogerty is in good spirits. The title of his new album -- a long overdue collection of his Creedence and solo hits -- is aptly entitled The Long Road Home. And it has been not just a long, but a litigious, road.

From heading a world beating band -- by the time they played Woodstock in '69 they were racking up back-to-back hit singles -- went to being mired in litigation with his record label and former band mates.

He became so bitter that for almost 20 years he refused to play Creedence songs in his solo shows. And consider what those audiences missed: Proud Mary, Bad Moon Rising, Have You Ever Seen the Rain?, Green River, Down on the Corner ...

The middle son of a working-class family from San Francisco's Bay Area, Fogerty soaked up 50s rock'n'roll and black music from the radio, formed a garage band with his brother Tom and -- with bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford -- and they went through a series of names (as the Golliwogs they flopped) before settling on the CCR moniker and refining their sound around Fogerty's vocals and guitar.

He might have been a Californian kid but his heart was in the South and songs like Born on the Bayou, Proud Mary and Mardi Gras came to define swamp rock.

Signed to Fantasy -- a jazz label headed by Saul Zaentz (later a film producer and owner of the rights to The Lord of the Rings) who wanted to break into the rock market -- CCR had a dream run. Their first tape, an eight-minute version of the old Suzie Q hit, was picked up by alternative radio, their second album Bayou Country in '69 sprang Proud Mary (number two in the States and covered by Ike and Tina Turner), and subsequent albums and shows confirmed their reputation.

While bands were playing sprawling psychedelic rock, CCR kept things tight and based their sound on classic rock'n'roll structures. Travelin' Band and Lodi define respectively the excitement and ennui of being in a rock band; and with Fortunate Son, Bad Moon Rising and Run Through the Jungle Fogerty captured the disenchantment of the Vietnam era.

However, after the departure of brother Tom in late '71 Creedence limped through a tour wracked by dissent and after the disappointing Mardi Gras album in '72 they split. They'd sold 100 million records -- but Fogerty had signed away his song copyright to Zaentz and on reflection felt CCR's career had been mismanaged.

On his Centrefield album of 85 he wrote Zaentz Can't Dance ("but he'll steal your money"). Zaentz threatened to sue so Fogerty changed the title, but Zaentz -- at the urging of Cook -- took him to court arguing the hit Old Man Down the Road from Centrefield ripped off Creedence's Run Through the Jungle. Fogerty was being accused of what? Self-plagiarism?

"It's comical on the outside," he says in a deadly serious monotone. "But I was spending a whole lot of money and time with lawyers and I can't imagine a more depressing way of life. But the Creedence they were talking about [in court] was the one that I wrote the music for, sang and did the guitar playing for. That sound is my sound."

Fogerty won the case and in '93 refused to play with his two former band mates (brother Tom died in 1990) when Creedence was inducted into the Rock'n'Roll Hall of Fame by longtime fan Bruce Springsteen. He has had nothing to do with Cook or Clifford -- who tour as Creedence Clearwater Revisited -- to this day.

He wouldn't play his Creedence songs again until 1990. He changed his mind during an epiphany at the grave of bluesman Robert Johnson in Mississippi.

"He was having a resurrection of his career and I was sitting wondering who owned the music. I got a very perverse image in my mind of some shyster lawyer.

"Then I thought, 'it doesn't matter'. Robert is the spiritual owner of his songs. Right after that I thought, 'John, that's like you. You're the spiritual owner of your songs.' That was a very powerful moment for me and my pathway out of the conundrum I'd got myself into.

"I thought the reason I was going to Mississippi was to look up the old blues guys but years later I realised it was so I could be at Robert's grave and start singing my songs again."

An hour later Fogerty sprints onto the stage and launches into Travelin' Band then Green River. He is in excellent voice and, driven by a five-piece band which includes rockabilly guitarist Billy Burnette, promises to "play some rock'n'roll for y'all".

For more than 90 more minutes he does -- It Came Out Of The Sky, Run Through the Jungle, Rockin' All Over the World (which Status Quo adopted as their signature anthem), and an angry Fortunate Son as resonant as it was in the Vietnam years. But there is also country music (Hank Williams' Jambalaya) and plenty of swamp rock.

He takes the spotlight for a solo version of Deja Vu, the moving title track of last year's solo album which sounds full of resignation about the war in Iraq: "Do you hear them talkin' 'bout it on the radio, did you read the writing on the wall, did that voice inside you say I've heard it all before, it's like deja-vu all over again."

Later in the song he telling changes a few words and the line becomes, "did you stop to read the writing at The Wall", a reference to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC.

Fogerty has channelled the feeling of many of his generation in the song, and has reconnected with his audience since starting to play Creedence songs -- his songs -- again. And with his old label Fantasy sold and under new ("delightful", he says) management he now has the career-encompassing compilation album The Long Road Home released.

"Life is good now. The Long Road Home represents a vindication. Now we can see John in his Creedence days and right on up to now. That's a great feeling of closure because my fans can now see that oneness.

"A lot of people know about Creedence but not who John Fogerty was -- which is ironic," he shrugs, "because John wrote and sang and produced all those songs."

John Fogerty cocert review. Auckland Civic Theatre, December 2005

Someone once said if you could identify a singer three words into a song they’d probably be in the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame. John Fogerty -- singer, songwriter, guitarist and producer for Creedence Clearwater Revival in the late 60s/eary 70s -- was inducted into the Hall of Fame (with his former, but estranged band mates) in 1993.

It was long overdue: Fogerty’s songs are usually identifiable from the opening riffs even before he opens his mouth.

And at an impossibly youthful looking and enthusiastically energised 60, Fogerty delivered hit after hit like some human jukebox to a capacity Civic crowd which bayed with recognition at songs like Lodi, Hey Tonight and Travelin’ Band then danced in the aisles to Down on the Bayou and Bad Moon Rising.

When Fogerty kicked off Green River with a guitar sound he could patent or the metaphorical Who’ll Stop the Rain you were reminded of what a songwriting genius he is.

Being identified as the man who first defined swamp rock (Bayou, Bootleg, Proud Mary), hardly does him justice. He also pulls in a distinctive take on soul (Heard It Through The Grapevine), old time rock’n’roll (Centrefield starts like La Bamba and references Chuck Berry’s Brown Eyed Handsome Man), funky country (Round My Backdoor) and the blues (Midnight Special). It’s fair to suggest Fogerty’s evocative Americana (Proud Mary, Long As I Can See The Light) anticipated The Band.

And he is an impressive lyricist (“wondrous apparitions provided by magicians“) who -- as he did on the anti-Vietnam/anti-privilege song Fortunate Son, given a blistering live treatment -- still connects to his generation. His melancholy Déjà Vu about the weary familiarity of the war in Iraq shifts from “the writing on the wall” to “the writing at The Wall”, a reference to the Vietnam memorial wall in Washington DC.

But that’s the serious stuff. Mostly the happy crowd were there to enjoy the rock’n’roll spirit he conjured up, and he did that effortlessly.

Every classic hits radio DJ should have been there forking out for their own tickets. This is the man whose readily identifiable songs have paid their wages for decades.

Long may he keep on chooglin’.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the New Zealand Herald www.nzherald.co.nz in 2005

post a comment