Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Grace Slick: Come Again? Toucan? (from Manhole)

The New York garageband Blues Magoos'

Psychedelic Lollipop of 1966 was one of the first albums to have the

word “psychedelic” in the title, but it wasn't quite the

spaced-out sweet thing the name suggested.

13th Floor Elevators out of Texas the

same year with their debut The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor

Elevators were more like the real thing: Psychedelic Sounds is

considered a psyched-out classic.

By the following year – 1967 with its

famous Summer of Love – the drugs, Indian music and guitar solos

had really started kicked in. The word “psychedelic” really

started to mean something. Although different things to different people . . .

Moby Grape and Country Joe and the Fish

out of San Francisco delivered debut albums which were sufficiently

pop-rock to keep your attention, but also somewhat mind-bending.

Jefferson Airplane – alongside the Grateful Dead – were banner-wavers for psychedelic rock and a musically powerful unit: singer/guitarist Marty Balin, singer/keyboard player Grace Slick (from The Great! Society who had replaced Signe Anderson after their debut album); rhythm guitarist Paul Kantner; lead guitarist Jorma Kaukonen; bassist Jack Casady and drummer Spencer Dryden.

And all of them, to a greater or lesser extent, wrote.

But by 1969 with the album Volunteers –

just two years on from Somebody to Love and White Rabbit – they had

abandoning the whole Summer of Love vibe for more direct militant

rock (the Dead's Jerry Garcia among others parting company

philosophically).

Two more years on and they were split

internally: Dryden left in 1970, then Balin quit the band he had

founded and critic Lester Bangs was writing of “the fire of the

Kaukonen-Casady combination (one of the great lead/bass juxtapositions

of all time, in the context of the Airplane) and the bambastic [sic]

excesses of the Slick-Kantner axis, who, after all, wrote most of the

songs and have increasingly stamped the group's identity with their

own sensibilities”.

Yet despite diminishing musical returns

the Airplane kept on: the first post-Balin album Bark wasn't up to

much in the lyrics (an increasing failing, Pretty As You Feel boasted

a great menacing tune but teeny-bop sentiments) and in '79 the

Rolling Stone Record Guide wrote it off as “wretched”; and they

split off into side projects.

Blows Against the Empire in '70 was a

concept album under Kantner's name (which included many Airplane

members and fellow travelers including Slick, and Jerry Garcia) which

he'd worked up while the Airplane were in-fighting.

Blows Against the Empire in '70 was a

concept album under Kantner's name (which included many Airplane

members and fellow travelers including Slick, and Jerry Garcia) which

he'd worked up while the Airplane were in-fighting.

It was also the

first time the name “Jefferson Starship” appeared (on the cover

beneath Kantner's name) although the post-Airplane band of that name

didn't arrive until four years later – but it was inauspicious

unveiling of the name.

Perhaps it was the acid, perhaps the

mood of the times – but a concept about people fleeing “Uncle

Samuel” and oppression by stealing a spaceship and looking for a

new home isn't the strongest of ideas, and hardly seems a blow

against the evil empire of Amerikkka, more a flight from the

frontline.

There are also some seriously

addled/naive lyrics (a tree which grows babies?) and – aside from

the experimental suite on the second side, the star trek -- the

music is hardly memorable.

Ed Ward writing in Rolling Stone was

merciless: “If Paul Kantner really thinks that the pap he is

serving up here is a blow against the empire, I suggest he takes a

bowl of oatmeal and a spoon and start throwing oatmeal at some of the

buildings he'd like to see topple and see how long it takes. What it

is, is a blow against the sensibilities of anyone who has come to

expect reasonably sophisticated music and lyrics (sophisticated for

rock lyrics, anyway) from Paul Kantner and the Jefferson Airplane.”

It did however become the first rock

album to be nominated for the Hugo (sci-fi writing) awards.

The following year Kantner and Slick – who by this time were a couple with a baby, China -- came out with Sunfighter (that's China on the cover) which divided Airplane loyalists: Some dismissed it as Kantner/Slick indulgence about parenting and

some hippy-dippy concerns (although Diana was inspired by Diana

Oughton, one of the revolutionary Weathermen killed when a homemade

bomb she and others were building blew up their New York apartment).

The following year Kantner and Slick – who by this time were a couple with a baby, China -- came out with Sunfighter (that's China on the cover) which divided Airplane loyalists: Some dismissed it as Kantner/Slick indulgence about parenting and

some hippy-dippy concerns (although Diana was inspired by Diana

Oughton, one of the revolutionary Weathermen killed when a homemade

bomb she and others were building blew up their New York apartment).

Others heard beautiful songs on an album about personal and social renewal. ("An excellent set, able to withstand comparisons with any of early seminal Airplane work," said the '78 NME Encyclopedia of Rock.)

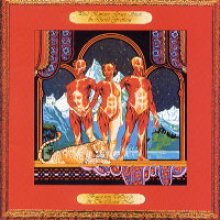

More interesting however was Baron Von

Tollbooth and the Chrome Nun from '73 by Kantner, Slick and

bassist/singer/keyboard player Dave Freiberg (from Quicksilver Messenger Service) who had joined the Airplane the previous year. The album also had the Dead's Garcia on guitar,

mandolin and banjo, and guitarist Craig Chaquico.

Tollbooth/Chrome Nun (the title referred to Crosby's nicknames for Kantner and Slick) was widely

considered the best album by Airplane's crew since Crown of Creation

in '68.

Tollbooth/Chrome Nun (the title referred to Crosby's nicknames for Kantner and Slick) was widely

considered the best album by Airplane's crew since Crown of Creation

in '68.

The shapeless solos had been trimmed and no “concept” weighed it down; there were dreamy, trippy songs from Kantner (Mind has

Left Your Body) and drama from Slick's powerful voice (the tough

Across the Board, Fat with the Pointer Sisters on backing vocals); rousing political and social sentiments (Flowers of the Night); Garcia is terrific everywhere (especially on the country-flavoured

Walkin') and it ends with the gorgeous, mysterious Sketches of China

which could have been about the country or Kantner/Slick's daughter. There is also Slick's raunchy Across the Board (“seven

inches of pleasure, seven inches going home”).

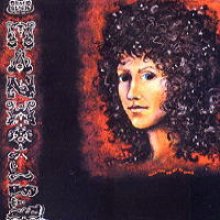

Slick's first solo album Manhole ('74)

found her with various Airplane members, David Crosby and the London

Symphony Orchestra.

Manhole -- the title a typically smutty Slick snicker -- is odd but interesting.

Manhole -- the title a typically smutty Slick snicker -- is odd but interesting.

It opens with a gently evocative Jay with wordless lyrics then there is the increasingly soaring, orchestrated, Spanish-inspired and quite exceptional 15 minute title track, the soundtrack for a film never made.

Toucan, Come Again

is beautiful ballad (music by Freiberg, the mercurial guitar by Chaquico) and the closer is Epic #38

which is an orchestrated suite and comes with heart-stirring

bagpipes.

And Better Lying Down was a

straight-ahead blues with Pete Sears on barrelhouse piano.

It is one of the most overlooked Airplane-offshoot albums and Slick, unfortunately, wouldn't make another solo album under her own name until 1980.

And then, against the odds as there had

been so many side projects – including Hot Tuna which was an

on-going vehicle for Casady, Kaukonen and others – the Airplane

resolved some differences and reformed in '74 . . . as Jefferson Starship.

Things began well enough with the debut

album Dragon Fly then the chart-damaging Red Octopus – but

thereafter the Jefferson Starship name was tainted by

increasingly bland albums which eventually lead to Bernie

Taupin-penned AOR stadium rock of We Built This City in '85, which,

ironically was a line-up with no original Airplane/Starship members

other than Slick (who had joined after the first Airplane album

anyway).

It was a strange flight the Airplane/Starship had taken.

From Balin being bashed by Hells Angels at Altamont to commercial corporate rock; from stoned psychedelic then rabble-rousing revolutionary rock to spaced-out sci-fi . . . and finally stadium pabulum.

How the mighty had fallen.

Want to read and hear more psychedelic music of the period? Then your trip starts here. The '93 Jefferson Airplane box set is essayed here.

post a comment