Graham Reid | | 7 min read

At the end of a digressive conversation with John Cale, I thank him for his time then add, "and I didn't even mention The Other Band".

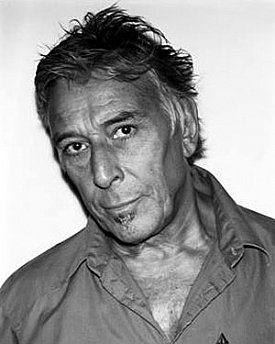

Cale -- Welsh, classically trained and fiercely intellectual -- lets go a baritone chuckle and says, "and thank you" -- then makes his escape, as if fearing inevitable questions about it may come.

The Other Band was The Velvet Underground. But since he quit in 1968 after repeated disagreements with Lou Reed and the band's first two, and best, albums - Cale's wilful solo career has been often brilliant and sometimes wayward, but always worth following.

He has written many soundtracks (a lot of them for French film-maker Philippe Garrel, American Psycho), released albums of contemporary classical instrumentals or uncompromisingly confrontational rock, adapted Dylan Thomas poetry into song, turned rock classics such as Heartbreak Hotel and Walkin' The Dog into hellish visions, and collaborated frequently with Brian Eno.

Cale is also a producer whose speciality seems to be delivering astonishing debut albums (The Stooges, Patti Smith, Modern Lovers) and working with people as diverse as Jennifer Warnes and Squeeze, Nico and Jesus Lizard.

So nattering to Cale - now 63, affable and on a late-career roll with an album called blackAcetate - about The Other Band hardly seems relevant.

Especially when the typically diverse blackAcetate betrays the influence of funk, weird alt.country and hip-hop, and includes two blistering songs (Turn The Lights On and Perfect) which almost sound pitched to an audience listening to Interpol, not knowing they borrow from The Other Band.

Surprisingly, the first music Cale mentions in relation to blackAcetate is Snoop Dogg's last album. Last September he was writing and recording for the follow-up to his acclaimed Hobosapiens and by late November he and a large band - which included two bassists (one of them Flea) and a couple of guitarists - had recorded almost 40 songs.

"Then the Snoop record [R&G: The Masterpiece] came out. I'd been listening to a little bit of his stuff before, then [the single] Drop It Like It's Hot happened and I realised I was barking up the wrong tree. The essence of Drop It Like It Hot's production -- it's Pharrell [of the Neptunes] -- is just minimalism of the most effective kind. I thought we had to go back to the drawing-board and drop the bass. When I dropped the bass I heaved a sigh of relief because I didn't have to worry about chord changes, I could just work on the pulse. Now the band going on the road will be just four of us."

Cale still looks forward to touring because his shows always have an element of risk as he improvises songs, changes the set list and arrangements, and writes new material during sound checks.

One of the songs on blackAcetate, the gritty and upbeat Perfect, was originally a throwaway written in a dressing-room in Amsterdam: "Then in the studio we had this discussion about it and what a knucklehead song it is. But at the same time I was thinking the power of the spoken word and a delivery which means that it doesn't come out the same anymore."

And that it might appeal to Interpol fans?

"I'm not indifferent to it," he laughs, "I just take it as it comes. The lyrics are: 'I'm not perfect, but you're perfect for me'. So it's more than just a knockabout riff. As long as I come through as John Cale I don't mind, as long as people recognise that and think: 'Well, he's not trying to do something else'."

However, the man renowned for his menacing baritone opens blackAcetate with a surprise - he adopts a falsetto for Out of the Bag, as if to put his audience on notice that this is no ordinary Cale album, if there is such a thing.

"Yeah, people have said, 'You know you don't have to sing it up there, you've got a really good voice down there'. But it loses its charm and fun quotient when I've it done down below. It didn't work."

Then there is the funk-minimalism of Hush, which he says started with the noise like the buzz you get from a refrigerator or a generator.

"I loved that buzzing noise. Of course we had to drop it out in the song because it would drive you nuts, but I think we can work it back in somehow."

blackAcetate is at it best in a bracket of reflective songs in the middle which are notable for their astute production and subtle instrumentation. The banjo and slide on the bayou-like In A Flood ("one of the earlier songs we had but because of the beautiful atmosphere we kept it") and the Eno-like arrangement on Satisfied, which could have come from Blue Nile, remind you how Cale has spent a large part of his working life.

He is still often approached to produce but considers it like an industrial process which takes six weeks, and with film and touring commitments he rarely has that much time. Big soundtrack projects such as American Psycho demand that he be available for every part of the editing process, but for his most recent music for the suicide-noir Process he knew the sensibilities of the film so could write mood pieces to fit.

He talks about playing older, heavily political material in his live shows but says songs like the bruising, apocalyptic Mercenaries might not be relevant.

"It was about a soldier marching to Moscow, nowadays it would be someone who'd want to go and take back the White House. I don't want to go that far, it's a character song - but would work great as a country and western song." And he's serious.

The rapidly conducted conversation continues, Cale taking off on tangents: how good Gorillaz are; how playing in Wales means working the tough audience of Manic Street Preachers fans; of lounge versions of Metallica songs; how he wishes more people had heard his Artificial Intelligence album of 1985 ("some very good songs on there"); of his long-time interest in the conspiracies and the hidden stories behind news reports ... then he drops an anecdote about when he came to New Zealand in the early 80s.

"I went to the local Communist Party meeting and there were all these old hippies with damp woollen cardigans, dirty sneakers and rolling their own cigarettes.

"There was a guy giving a speech, the leader of the Philippine resistance movement. When he was in New Zealand he was dressed like a bum and his opening remarks were: 'The infection has been lanced but the limb is still infected,' and he meant the Marcos family, which he wanted out of power.

"Then I went to Sydney and on the Sunday he was on television. He had a beautiful blue blazer and blue tie, dressed like a businessman, and he said the same thing."

"And about a week later he became a lecturer in some Australian university. It felt like I'd been watching a movie."

He laughs and it is time to thank him - still without mentioning The Other Band.

No time, as it turned out.

post a comment