Graham Reid | | 22 min read

Howe Gelb and A Band of Gypsies: Cowboy Boots on Cobble Stone (from the album Alegrias)

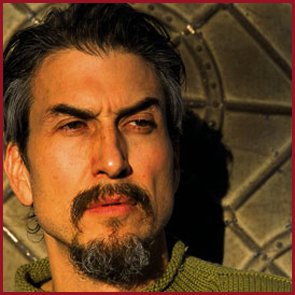

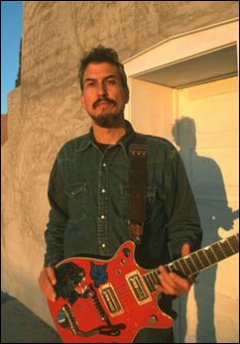

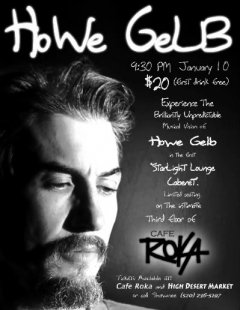

Howe Gelb of Tucson, Arizona is one of the long distance runners. He's been in for the long haul with his band Giant Sand (two dozen albums since the mid Eighties) and diverse solo projects under his own name (around 18 which range from gospel in Canada to flamenco desert-rock in Cordoba, Spain on his new release Alegrias).

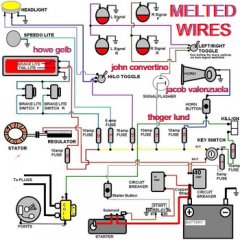

And there are other albums as OP8, the Band of

Blacky Ranchette, Arizona Amp and Alternator and more recently Melted

Wires with an internet only self-titled release (available here).

Gelb's music ranges from dusty desert

folk-blues with a twang of country to stride piano jazz.

He's a hard man to pigeon-hole –

which explains why Giant Sand have existed on the periphery of many

people's consciousness. It's their loss. He is something special and last year's Blurry Blue Mountain (a Best of Elsewhere 2010 album) is the ideal introduction.

As he acknowledges, he fell between

the counterculture of the early Seventies and the punk rock

revolution of the end of that decade. His music career was therefore

defined by Bob Dylan and Neil Young at one end and the DIY of the punk

ethic at the other.

Giant Sand – which began life in '93

– have remained an acclaimed cult act for decades now: their

membership changing in the early years with Gelb as the sole

constant. But two of its members – Joey Burns and John Convertino –

began to run a parallel band Calexico which went on to greater

success.

In this candid and lengthy interview

Howe Gelb – witty, self-effacing and honest – addresses some of

those matters, speaks about his new album recorded in Cordoba with a

group billed as A Band of Gypsies (which has been nominated as the best

“fusion” album in Spain, a description which amuses him because

its meaning is lost in translation), his extraordinary internet only

album Melted Wires (with drummer Convertino, available here) and how he has managed

to keep Giant Sand and an exceptionally prolific solo career going

for so long.

He talks about obsessive German

collectors, the joy of being in Cordoba, and of how there was a

difference between “millionaires and thousandaires” in the music

game. U2 Vs Giant Sand in other words.

“But this is the benefit of not being

too popular. I don't have to wait two to four years for every new

release. Instead of making one record that sells 500,000 copies I can

make 40 records that will sell a total of 500,000 and I don't mind

doing that.”

However his career choices came at a

price he notes, but he's still here -- and we spoke as a massive

Giant Sand and Howe Gelb reissue programme was launched, around 30 albums in total.

Before we got down to business we spoke

of newsrooms staffed by young journalists with little background

experience (not like Walter Cronkite whom you could trust), he spoke

warmly of Auckland musician Chris Knox who had a stroke two years ago

and whom he knew from playing in New Zealand, sent his condolences

for the city of Christchurch where he had played, and how his last

solo tour in New Zealand five years ago faltered because of poor

promotion by a local enthusiast.

Which is where we pick up the

conversation . . .

I am guessing that early on certain

people all over the world would hook into your music and get it. Did

you initially do a lot of touring on the back of fans inviting you to

play.

Yeah, we did it both ways because I

came from a point of sonic existence between punk rock of the late

Seventies and the counter-culture of the early Seventies, like 69-72,

when I started listening to music. So in that space when we started

making music, that was the ethic we carried with us. And when punk

rock came around that made the most sense, even though my godfathers

were Bob Dylan and Neil Young and that ilk of wordy songwriter with

cool guitar leads.

Punk rock freed everybody up and you didn't have to know how to play so much because it was all about attitude. It also meant you needed to do it yourself and not rely on anybody else and that ideology has sustained me from the very beginning. When I finally figured out how to make records in the mid Eighties I only licensed them, I never sold the rights to anybody. Which meant I always keep ownership of them and they would return back to me at some point.

I didn't even know why that was important

but I just felt it was better that I had them than someone else had

them who didn't care later on.

The downside of that is that if a

company has more of an investment in your records then they will work

harder to get a return on that investment as income. So that left us

at a certain level of notoriety and allowed us to stay alive as long

as we have, 25 years or so, but also kept our level of availability

or prominence to a less than household-name level.

Then there has been all these ways of

touring. Sometimes we would use touring just to go a certain place,

just as a vehicle. Like, if I wanted to go to New Mexico for the

weekend I would set up a show accordingly.

Then there has been all these ways of

touring. Sometimes we would use touring just to go a certain place,

just as a vehicle. Like, if I wanted to go to New Mexico for the

weekend I would set up a show accordingly.

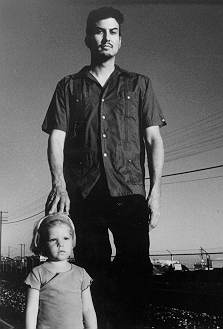

And now we do that with the family. If

we want to go to Greece we'll set up a show there. So we do it in a

way which means we haven't applied it as a form of show business . .

. and sometimes it's not even entertainment but it is something else.

Every time I go out these days,

especially in the last few years, I wonder who my audience is.

I think it's mostly younger musicians

who have found their way there, and there is some kind of embedded

code in the albums which makes a lot of sense to someone starting out

making their own music.

Then there's also my voice which has

gotten more of a baritone and has more of a comfort zone instead of

something on the edge, and that seems to have lured in more young

women. I think that is maybe because of the voice.

We have a wide range of people coming

in, there's my age or older who got into us when they were young and

they're approaching 60 because I'm 54. Or you have the younger musicians

starting out and these young women bringing their boyfriends. I can't

make much sense of it.

I saw Leonard Cohen recently and aside

from women in their 60s for whom he was still a sex symbol there was

an enormous number of young women. I could only think there was

something in his voice which attracted them, they didn't look the

kind of people who would be studying modern American poetics at

university.

I don't think it has to do with the

father figure either, it's sort of where the maturing male is headed

to with that resounding texture of a voice that it falls into at some

point later, and because it is slower than ever it is also more

approachable. It doesn't chase after you, it sets up the perimeter

and within that there is space and time enough to reflect. It offers

some kind of . . . deployment of enjoyment.

Maybe it's that Walker Cronkite thing

we were talking about. “Here's a man I can trust”.

(Laughs) That's it. You summed it up

right there and I took like 12 minutes to get to that.

Let's go back to that ethos you were

talking about when you started out. Is that why you denied the notion

of the band? There's always that band/gang thing which explains why

U2 are together after all these years, they are the last gang. But

that hasn't been the case with Giant Sand with its revolving door

membership.

No, but that was the intention. The way

life was playing I wasn't able to do it as such, but that would have

have been the best way to do it, like the letter bands . . . REM, U2

. . . It's why we formed OP8 and thought that was going to go the way

of the other letter/number bands.

But there was a series of incidents

that determined otherwise and if I had my druthers I still think that

is the best way to do it.

But when you look at Bob Dylan and Neil

Young . . . Dylan had a revealing line in his Chronicles when he said

every time he would put a band together – in Minnesota or New York

– someone else would come along and steal his band,. Someone with

more stage presence or a better voice would like his band and didn't

care for what he was doing, so they took his band away.

So it's not that hard to do because a

player, especially that young, wants to go with the best ticket,

especially if they are not writing their own material and they have

to rely on enough gigs to get by. So they want to go with the best

ticket and I think that scarred him because in all the years that

followed he kept changing members in his band.

The same with Neil Young, although for

different reasons. Because I think he was so fired up and moving so

quickly that it might have been because he knew at any moment it

could be over and no one could keep up with him, especially after

Buffalo Springfield.

Those two guys seemed like having a

whole band could not apply to them, although they both look a little

sad for it too. It is just so much more protective to be in a posse.

But I just listened to the last REM

album and two thirds of it sound like every other REM album I've ever

heard. That's the constraints of a band. One of the things about

Giant Sand I've always thought is that it is a moveable . . .beast.

I was going to say "feast" but "beast" sound better, that whoever comes

in brings something different for you, or you offer them an

opportunity. And for me as a listener that just seems more

interesting.

Yeah, but there's a difference between

millionaires and thousandaires. If you offer something that is easily

explainable and can be noted what kind of music it is and what you

are going to get, then you can establish a growing audience that

won't feel jerked around by surprises.

Yeah, but there's a difference between

millionaires and thousandaires. If you offer something that is easily

explainable and can be noted what kind of music it is and what you

are going to get, then you can establish a growing audience that

won't feel jerked around by surprises.

I'm one who likes surprises.

That's the thing. You can get a job in

this life . . . and here's the wisdom of an elder . . . you can pick

a vocation that you are passionate about or you pick one that will

allow you to have a hobby you are passionate about, so you don't ever

have to tax that hobby with the pressures of stress and making a

living. But that hobby could be your vocation, but when you embrace

it, it enslaves you because there are times you have to do things,

like relentless workloads. Which way is better?

I don't think either is better, it is

just a choice you make. The same thing goes for, if you want to talk

about music, are you going to make music you can be more strategic

with to get to a certain place and get what you want out of it,

either materially or to some higher echelon? Or are you going to make

music you are more comfortable with and you prefer to buy and listen

to?

In my case it was the latter and I thought that would also allow longevity. It did allow that, but only to a smaller audience. The only thing about its lack of appeal now is when you have children. Making music without children attached is really easy, you don't realise how easy until you have children. Then making a life in music means you have to cut your time completely in half, at least. And when that happened with me I had to chose what territory I would spend most of my touring time in.

I chose Europe

because it was so much more conducive on so many levels. But now I'm

sorry I didn't work the States more because I don't like to travel so

much. I love being anywhere in the world, but I hate getting there.

You used to spend a good deal of time

in Denmark because of the family. Do you still do that?

You used to spend a good deal of time

in Denmark because of the family. Do you still do that?

Well, that's because the kids have three months off school, so that allowed us to go there where my wife and her people are from and spend three months there. And it made sense because I could play some shows and it would pay for the whole summer. Most Americans can't afford to spend that much time in Scandinavia because it's so expensive.

There's also a weird cultural

thing where they rent houses there, it's part of the constitution,

who has a family has a small one or two room garden house, what they

call a colony house. Therefore there are loads of these apartments

you can rent or sublet during the summer. All those things made it

possible.

Plus it was the whole time Bush was in

office so it was good to get the kids out of The States so they could

pick up a global attitude, and a second language.

Let's talk about a second language. I

understand you don't speak much Spanish at all.

No. I barely speak music. It occurred

to me when I was in Denmark when people asked me why I didn't learn

the language – and you can't help but learn some of it, I've

learned about 10 different menu languages – but there is a perverse

pleasure being in a crowded area in Denmark for example and only

enjoying the murmur, the cello-like tones of the human voice without

the meticulous exhausting details and the complexity of their lives.

That means they could be talking about me? That seems a fair

trade-off.

The reason I ask about Spanish is

because I want to talk about the Alegrias album. You just communicate

purely through music with someone like [guitarist] Raimundo Amador

because he doesn't speak much English, does he?

The reason I ask about Spanish is

because I want to talk about the Alegrias album. You just communicate

purely through music with someone like [guitarist] Raimundo Amador

because he doesn't speak much English, does he?

No. It's usually though music and

laughter. These are positive and joyous elements. It's pretty cool

when you don't get to know the details of somebody's life which

absorb so much of our contact with that person. If it's only music --

and I don't know how but we sometimes know what each other is talking

about when we crack up laughing – it's a pretty fine way of

naturally editing the dialogue.

So all the detritus of life disappears.

I imagine it is quicker too.

I love my friends and I go the studio

here in town and the guy who runs the studio is my age and we will

talk for an hour and a half before we get anything done. As you get

older you have a habit of enjoying each other more, because when your

friends get sick or die off you savour any time left with anyone you

know. (laughs)

When you make friends all over the

world it's kinda cool not being able to talk so much and you just get

down to work.

It's a beautiful album. Congratulations

on nominated for the best fusion album in Spain.

(Laughs) But if you translate an album with

“fusion” right? It is “con-fusion” because the Spanish word

for “with” is “con” and “fusion” is “fusion” . . . so

it was “con-fusion”.

When it came to choosing material for

the album, had you sent the Band of Gypsies tapes of the songs?

No, it was just as organic as getting together any other group of people. When I describe it, it will seem more more romantic . . . and in a sense it is. But it was also very natural, just the order of business in that culture and that place.

In Cordoba, a friend of mine Fernando Vacas kept inviting me to his

home, and like many people who extend invitations and there is no

time especially if you have the family back at home in Tucson.

Because you can only be out on the road so long.

As it turned out one time we had two

days and when I was there the town, bizarrely, it felt more home than

home. It felt more like Tucson than Tucson and his house was very

like the one I live in here, these old adobe house with thick walls

and there are no right angles. And like the adobes here they have a

courtyard, and there they are built for the heat. The weather is

exactly the same as Tucson but it is more sensible there because the

roads are narrower to shadow you from the sun.

The food was simple and good, and his

recording studio was in a converted shack on the roof, like a pigeon

coup, two tiny rooms and one he converted into a studio and the other

he put up an engineering board.

And we would gather on the rooftop and

the evening air was so much like Tucson and the heat. And one by one

these gypsies would show up, his friends and people he knew, and

that's what enticed me to begin with.

I couldn't imagine it, but loving

guitar as much as I do I was intrigued by someone who could play that

well, and to find out if we could even meet on the same page. So we

did get together and they started showing up and we were circling

each other. We were all being a little protective and standoffish, and when

they played they blew my mind. They use all their fingers!

And they play like their people

invented guitar . . . and of course they did, they stopped the

evolution of the guitar as it came up from Africa, and that is the

guitar we play today.

So all I could do to impress them was

to play some stride piano, which for some reason I have been playing

for the past five years or so. Those guys could play any instrument

but none of them could play that style of piano. So it was like I

gave them something they could find fascinating, the way I was

finding their playing fascinating. And it was just enough, like an

unwritten right to allow to us to now feel more comfortable with each

other.

I didn't really play piano on the record, I played guitar and when I played they would crack up over my weird notes which they found entertaining. I was stunned and fascinated by their whole different way of playing. The more I hung around them the more I learned. Like how they would clap to their babies those crazy flamenco beats which I still can't understand, and the babies would light up when they clapped to them. And when they were four or five [the children] would hang out in the small clubs until 4 in the morning while their dads would play music.

The whole

culture made more and more sense when I was there absorbing it and I

found myself going there more and more whenever I could.

Making a record was an excuse to be in that town.

And it is predominantly your material

and you were presenting your songs to them?

And it is predominantly your material

and you were presenting your songs to them?

I was staying at Fernando's house and I

started writing more and more songs. It was the same thing when I

went to Canada to do the gospel choir record, so I used the same

template where I would look at my catalogue and think, The Uneven

Light of Day has some chords that are flamenco-like . . . just like I

did with the gospel choir where Roots Are Bible Black had a gospel

element . . . and I applied that accordingly.

Back when I made all those records I

was making them very fast and didn't start making records until I was

28, which I thought was late in the day. I should have started when I

was 24, but in Tucson it was difficult figuring out how to do that in

1980, so it took until '83 or '84 to figure out where to record, how

to record fast and do it in a day and spend $400 then license the

thing for $1000.

That was that template. Then that would

grow and they would give me $2000 and I would make the record for

half that or $1500, and I would do it in a day or two. That's how it

started, but by doing those records so fast the material seemed

relatively easy to come up with. My songs aren't that sophisticated

and there's not a high degree of harmony or stylistic melody played,.

They are somewhat . . . easy. And I would do a lot to keep the band

working and to keep records happening so we could keep touring.

So you have me as a performer and me as

a songwriter, two different people. And as a songwriter I knew many

of those songs weren't executed the best they could be, but it wasn't

until the late Nineties that I tried to focus in on that.

So when it came time to do the gospel

record I could look back on the vast catalogue as if it was a song

bank and then make withdrawals from the bank. Like, “Here are some

tracks that could have been played better but never were, and now I

can play them as if they are someone else's song and treat them with

respect by doing a cover of them”.

And that's what I did with the Spanish

record as well, but also writing a whole bunch of songs. I know that

when I'm in a good place the inspiration is to get in like that when

everything is happening as it should happen.

That degree of productivity has a downside though? I remember

mentioning to someone very enthusiastically that there was a new

Giant Sand album out and they said they might just miss this one,

they're like the bus. If I miss it there's another along soon.

That degree of productivity has a downside though? I remember

mentioning to someone very enthusiastically that there was a new

Giant Sand album out and they said they might just miss this one,

they're like the bus. If I miss it there's another along soon.

Yeah [Laughs] And that's exactly the way I feel, the way most humans feel. You are either going to be engaged by the Giant Sand collection – and some of these Germans are just imprisoned by it, they started making live tapes of every show in the late Eighties and now they feel they can't stop. [Laughs]

If they stop it discounts all that

energy and time they put in. So now they have to continue on, as much

as I punish them for every new release and every new tour, because

they have to get out there and capture it.

If you haven't made it easy for people

to digest your music, what you have is baggage, luggage and

exhaustion. When I hear of the Fall I'm glad they are still going,

but I don't feel compelled to go out and listen to another Fall

record.

I know that's the same with Giant Sand,

but I at least want to carry it on until the 25th year.

And now I love the band so much, these Danish guys I've had the last

nine years, it is just fun to do and a really good wall of sound to

be a brick in.

So it still has its relevance, but I

also am free to do these so-called solo records.

It seems just about every Giant Sand

album and album under your own name is coming out on reissue, so for

my friend who says he might just let the bus go past . . .

Well, he could enjoy the ride . .

I said get on now, the next one might

be in an accident . . .

(Laughs) Right . . .

But for him, are there some albums

you'd like to say, “If you hear nothing else by Giant Sand, or one

under your own name, then you do need to hear this one”?

Out of the entire release campaign –

I think there are about 30 coming out, not quite the full catalogue,

all of the Giant Sand plus some solo records – the one that is out

now, because they release them three at a time, Center of the

Universe [released in '92] would be a good one to drop into because that had some

really cool energy to it and great songs.

It was the only time I was allowed to

live how I always wanted to live, which was completely alone in a

small one-room cabin out in the desert. Shortly after that, within

three years, I had to move back to Tucson to put my first child into

school.

It was the only time I was allowed to

live how I always wanted to live, which was completely alone in a

small one-room cabin out in the desert. Shortly after that, within

three years, I had to move back to Tucson to put my first child into

school.

I was newly separated at the time so

moved to the desert in the Joshua Tree area to a cabin in the middle

of nowhere right past where the dirt road ended. So I had no TV and

the only entertainment I had was coming up with songs for myself. And

they seemed to come fast and furious and we recorded them the same

way.

They are really a lot of fun and that

record has a real good spirit. I can hear my focus because I was left

alone. I'm the kind of guy who needs two days to have one clean

thought, one uninterrupted focused thought. And with kids and family

and being in the city, that will never happen again.

So Center of the Universe. Go chomp on

that one! See if you can survive that.

It struck me that Blurry Blue Mountain

was almost the perfect intro to this reissue. Was it deliberate to

put these coherent but slightly different genres out there into the

world at this time?

It struck me that Blurry Blue Mountain

was almost the perfect intro to this reissue. Was it deliberate to

put these coherent but slightly different genres out there into the

world at this time?

If anything my methodology have always been organic, meaning that there's no formula except for trying to do things different every time. There always seems to be at least 1000 different ways to play a song, what if you attacked the lyrics this way? So it never made good sense to me to pick one way and stick to it even though that would have been the most marketable way.

That's not what I prefer. Life is like that, so full of variety, and life, through the miracle of erosion it changes the nature of the land daily and so should things be changed. That said this old planet was spinning faster years ago which is probably why in the Bible those guys lived to be hundreds of years old because the days were quicker.

But that is the natural state of this planet and as far as my records

go I think they are slowing down and don't seem such a blur at the

first 10 or 15. You can look at Blurry Blue Mountain and its clearer

than ever, regardless of its title.

You think, “Oh, this song is like

that and that song is like that, and they pretty much represent all

the genres we have done and seem to be able to do without much

trouble”.

However the thing about it, if you go

on the website it explains how the record got recorded when we are

all in the state of being half awake and it happened three times in

three different sessions and it really bothered me because we weren't

sounding as vital as we should. But then I thought, “This is cool,

I've never made a record like this.”

And because of that it has a coherence

to it. I'm going to ask you about one I didn't even know existed,

Melted Wires. You are one helluva jazz pianist, the piece Cordoba in

Winter is an amazing piece of music. You play a lot of piano these

days?

And because of that it has a coherence

to it. I'm going to ask you about one I didn't even know existed,

Melted Wires. You are one helluva jazz pianist, the piece Cordoba in

Winter is an amazing piece of music. You play a lot of piano these

days?

Yeah but I don't have a normal piano in

the house, that should have been rectified. I've got this one from

1888 before they had concert pitch. It is stepped down so C is

actually in B flat, so these things happen. (Plays some stride piano

down the phone.)

When I hear that I hear a Thelonious

Monk from 1930, there's something in the sound of the old piano but

also angular and Monk-like with a stride era feel.

That's where it came from when stride

yanked itself away from ragtime and had more improvisation and

rhythm. I don't know how or why I started playing like that. I really

enjoy it.

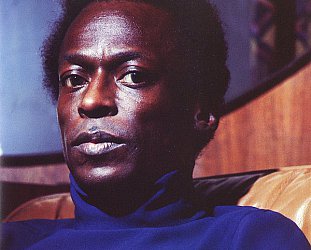

Melted Wires is attributed to Melted

Wires? It was recorded around the same time as Alegrias?

It was a year ago last September, there

was me and . . . you know there is a whole other hour of conversation

about the thing between Giant Sand and Calexico. But I have an

appointment at 1 o'clock!

I think I know a little about that

because I spoke with Joey once, but I was curious about the album.

You just managed to find the time . . .

(Laughs) I'm sure whatever you heard

from Joey was a plastic version of what actually happened. He figured

out a way of being in this band for a while, but to not use the more

gambling bits which have also been associated with Giant Sand, and to

clip off the stuff which lent to too much happenstance and keep it

more consistent.

Which is why [Calexico] have become

more popular. Which is what we were saying before: every Calexico

record will be like an REM record, it will be the same thing they are

doing every time for the benefit of their listener and themselves.

Because that is what they've got to do and when they veer away from

that as they tried to do with Garden Ruin [2006] they caught hell for

it. But they are happy because they can play with other people, but

when they do Calexico it has to be that certain suggested sound.

Joey has a tendency to be less

revealing about how he feels about things and more sensible on how

things should look. I tend to be more erratic and evocative and more

reckless with my feelings, I think feelings are reckless and I try to

reflect that. That's also the difference being 10 years older than

him too of course. He didn't come from the counter culture or the

punk idiom, he came from a whole different place and plays the way he

came from nicely.

That said the whole thing with Melted

Wires . . . When the bands began to split up the crowd was very

pulled because there were so many collisions because of the different

agendas and weird things none of us would have imagined. Like who

Giant Sand was. You had the younger people who only knew us when John

and Joey were in the band, but if you were a little bit older you

knew the band before Joey was in it. And of you were even older you

remember when John wasn't in it.

So what the band could do was being

taken hostage by Calexico's rise because it had two thirds of the

most current line-up of Giant Sand. I had to begin forming another

band because they were no longer available . . . and that didn't

happen directly, I went solo and then eventually realised I had a

band when I went out solo, but they were all Danish. And one night I

realised the stuff we were making was the same as we were making in

any form of Giant Sand.

So what the band could do was being

taken hostage by Calexico's rise because it had two thirds of the

most current line-up of Giant Sand. I had to begin forming another

band because they were no longer available . . . and that didn't

happen directly, I went solo and then eventually realised I had a

band when I went out solo, but they were all Danish. And one night I

realised the stuff we were making was the same as we were making in

any form of Giant Sand.

Then there were people always lamenting

we weren't playing together or thinking “Oh it's not the original

line-up”. But neither was that with them the original line-up etc

etc etc.

The bottom line was, I could not play with John without causing more problems to the people that didn't know what was happening and wouldn't allow Peter [Dombernowsky], to be the new John, or John to be the last Tom Larkins or whatever.

Somewhere in there

when I did the solo record with the gospel choir I had the drummer of

Arcade Fire right before he was in Arcade Fire, so it is tricky for

public perceptions.

People think they want one person over

another so therefore John and my ability to play together is now

severely limited. Melted Wires happened organically because my bass

player from Giant Sand now lives in town, but not the drummer, so to

get together we found ourselves taking on a benefit show and doing

rehearsals in the studio and I recorded them and after the fact I

realised there was a record in there, possibly.

And if you are familiar with W. Eugene

Smith then that was that template, because he wired up his loft and

recorded all those great beboppers including Monk. So that's all it

was, finding an excuse for us to play together which wouldn't be

harmful, or suggesting it was Giant Sand again.

Or the next bus?

Yeah (laughs) We're not sure where this bus going, but you can get on if you like.

The Howe Gelb/Giant Sand etc website is here.

Garth Cartwright - Jun 8, 2011

Great interview! You got so much more out of Howe than I did when I turned up in Tucson to intv him for More Miles Than Money. I guess he has a new album and the reissues to promote so was willing to give you the time while I caught him when he had no product to promote so he turned into the most difficult interview in the entire book! He's in London real soon performing the flamenco album but I'm not as enthusiastic about it as you so may pass on going. Listening to Lee & Nancy right now - Lee remains Arizona's greatest ever musical son. His eccentric solo albums surely impressed a young Howe.

Savepost a comment