Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Loretta Lynn: The Other Woman (1963)

The ugliest baby I ever

saw -- a pug-faced killer-midget with malevolent eyes -- was at

Loretta Lynn’s

place.

Then again, there was

plenty of ugly, kitschy, evil and just plain tacky stuff at the home

of this country music legend.

But I’ll

be forgiving, and say that maybe the baby just looked bad in

comparison with the delightful setting of Hurricane Mills, the

property Loretta bought in the late Sixtiess and which included a working

mill beside a pretty lake, and rolling fields in the lush landscapes

of east Tennessee about an hour from the capital of country music,

Nashville.

We had been driving to

Nashville on Interstate 40 when a sign loomed up on the highway

ahead: Loretta Lynn Dude Ranch.

Not having read her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter -- or having seen the 1980 film adaptation in which Sissy Spacek played Lynn and Tommy Lee Jones was Lynn’s husband Doolittle -- I had no idea Loretta had a ranch open to the public.

But the thought of it is too good to miss, so we pull off the

highway and drive to a restaurant-cum-gift shop on a hill above the

side road where Loretta’s

name was bannered large above the entrance.

Lynn -- who made her name

with appealingly earthy and honest songs like Don‘t

Come Home A Drinkin’

(With Lovin’

On Your Mind), The Other Woman, and Who’s

Gonna Take The Garbage Out -- is a country star of the old

kind. Her story of rags-to-riches has been told in her

autobiographical songs and two volumes of her life story (Coal

Miner’s

Daughter and the repetitive sequel Still Woman

Enough).

She sang of cheatin’

husbands, bein’

poor but still havin’

dignity, of belief in God when the world has done you wrong, and of

lost love. Loretta knew all these things from bitter experience.

That was the dude ranch,

this was just the merchandise store.

We drive through fragrant

countryside lined with wildflowers, cross Duck River (where Loretta’s

son Jack drowned in 84) and the road narrows to almost a single lane

through a silent forest. Down a broad driveway on our left is

Hurricane Mills, a small town of the original post office, a few

other buildings and the mill and wheel beside a flat pond.

It is as purty as a

picture and facing it across the river is the white columned house

which Loretta and Doo moved in to in early 67.

“It looked like a

hillbilly‘s

dream.”

Loretta -- and Doo, who

died in 96 -- moved out in the late 70s after fans just kept turning

up to the door (and some tempting boozy Doo off for drinks). But the

house has been kept as it was when they lived there.

And it’s

tacky.

Lynn’s

early life was unashamedly tough and she has written and sung about

how she grew up in remote Butcher Holler in Kentucky. She went to a

one-room school; their single-room handmade cabin was wallpapered

with pages from magazines; she wore flour sacks as a child and slept

on the floor until she was nine; and her father worked in the mine.

On the day of her wedding

in the local courthouse she needed to go to the toilet so Doo took

her to the bus station. She’d

never seen indoor plumbing and was terrified by the flushing.

Doo called her a stupid

hillbilly -- and Lynn admits she was. But forgive her, she was young.

Doo called her a stupid

hillbilly -- and Lynn admits she was. But forgive her, she was young.

Loretta married Doo when

she was 14 -- he was in his 20s and had fought in Europe in World War

II -- and had no idea how babies were made. She had four by the time

she was 18.

What separates Lynn from

many other successful country artists is she genuinely hasn’t

changed her attitudes: she doesn’t

know big words and doesn’t

pretend to; and admits to some hilarious gaffes.

When she was invited to a

Dean Martin Celebrity Roast for Jack Lemmon she didn’t

have any lunch that day. She was looking forward to the roast meat

and potatoes later.

Ernest Tubb, the country

legend who helped her career in the early 60s, said she was the only

person he’d

met -- and through the Grand Ole Opry he’d

met ’em

all -- who didn’t

change after she became famous.

Lynn has known six

presidents and in Still Woman Enough she says she

counted two of ’em

as friends, Jimmy Carter and the first George Bush. Of course she

supported George the Younger.

Yet while she has mixed

with the great and the good -- and the not-so-good -- she also

remembered what being poor felt like and so wasted nothing.

She kept the packaging

that perfume bottles came in and at Hurricane Mills there is a museum

filled with her dresses, concert posters, memorabilia and her old

tour bus.

Shortly after Doo first

met Loretta he gave her a baby doll for Christmas and said that when

they were married they would have a real live doll.

“I didn’t

know what he was talking about,”

she later said.

But, like most things in

her life, she kept that gift. The child-bride was, after all, still

playing with dolls.

Over the years as she

became wealthy they added to Hurricane Mills.

The day we dropped by

there we were a dozen other visitors to Hurricane Mills, among them a

couple who -- and I dislike myself for making this observation --

could have been siblings and had two slightly unusual looking

children with them.

The man was ill-shaven and

wore ragged denim overalls, and the woman a baggy hand-me-down dress.

They tip-toed around Loretta’s

house and gazed in awe at the hideously carved Indian kitsch on the

walls (Loretta was proud of her Cherokee heritage) and the cabinets

Doo built to house her collection of salt and pepper shakers and such

like.

They became reverently

silent at the sight of her gold and platinum discs in the stairwell,

and in the garden took dozens of photos of the hideous job-lot

statuary.

They became reverently

silent at the sight of her gold and platinum discs in the stairwell,

and in the garden took dozens of photos of the hideous job-lot

statuary.

These people --

worshippers in the church of country -- were Loretta’s

true fans and the people who gave her the career she has had. And she

never forgot it.

Hurricane Mills has trail

rides, camping grounds, fishing holes, regular concerts and an annual

MotorCross Championship. Loretta’s

constituency turns up in their thousands during the year and make the

pilgrimage to her house like others visit the Vatican or Buckingham

Palace.

“Horses down that away”

reads a sign.

I could only be cynical at

the reconstruction of the mine her daddy worked in -- it was kinda

dark and scary in there though -- but was impressed by the ebb and

flow of her career as outlined in the massive museum of her

memorabilia.

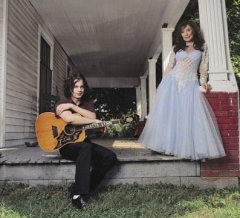

In '04 Lynn released an

album with Jack White of the White Stripes, and so Loretta -- at 69

-- was a cool name to drop among the hip set. People who’d

previously never heard a note she’d

sung suddenly confessed to being longtime closet fans.

In '04 Lynn released an

album with Jack White of the White Stripes, and so Loretta -- at 69

-- was a cool name to drop among the hip set. People who’d

previously never heard a note she’d

sung suddenly confessed to being longtime closet fans.

In a reminder of what a

footnote in her long career that association had been, two posters of

concerts with White stacked in a corner near the toilets.

But she had kept them,

just as she kept and displayed the gifts from fans.

Beside the shop was her

doll museum.

That is where I saw the

brutally ugly baby, in a glass case beside the Native American dolls,

those in chintzy wedding gowns, or dressed as cowgirls in gingham.

Awful stuff, all of it.

The ugly baby was on its

hands and knees, it’s

oddly distorted face twisted up into something between a snarl, a

grimace and a plea for help.

The ugly baby was on its

hands and knees, it’s

oddly distorted face twisted up into something between a snarl, a

grimace and a plea for help.

It‘s

pinched eyes were almost Satanic and, most curious of all, its

nappies were pulled down to reveal a round firm bottom raised in the

air.

It looked . . . well, creepy actually.

And not a little perverted.

I’m

sure that other couple and their kids will never forget the day they

went to Loretta Lynn’s

place.

Nor will I.

But for entirely different reasons.

This was a chapter in the travel collection The Idiot Boy Who Flew, see here.

Want to read more along these lines of music and travel? Then check out this one, a journey to Robert Johnson's crossroads.

post a comment