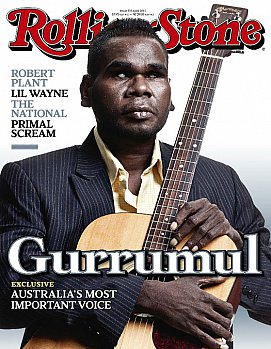

Graham Reid | | 11 min read

Gurrumul: Djarimirri

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu – known

to his people as Gudjuk and in the wider world as simply Gurrumul –

is an overnight sensation which has been about two decades in the

making.

The blind, self-taught,

singer-songwriter from an Aboriginal community on the small and remote

Elcho -- an island off the north coast of Australia near Darwin

(population 2300) -- has toured Europe to enormous acclaim, his debut

album Gurrumul (reviewed here) went gold in Australia, and his new one Rrakala (see here) went

straight to the top of the Australian charts.

He has performed before the Pope and the Queen, in concert halls and

at huge Womad festivals, and most often has hushed audiences with a

voice which his friend/mentor/producer and bass player Michael

Hohnen says possesses “a fragile beauty”.

And Gurrumul – who plays guitar

upside down – is an Aboriginal artist who doesn't have a digeridoo

within coo-ee of his music, and he doesn't – as so many Aboriginal

musicians do – play reggae or country music.

He just sings his songs which are deeply

imbued in the spirituality of his people in a voice which is

immediately engaging, and usually over a simple backdrop.

“I love the fact that people can buy

the album and not think, 'This is an Aboriginal record'," says

Hohnen from his office at Skinnyfish Music in Darwin. “I try not to

talk about [the Aboriginal aspect] because I know how much culture he has in him and

it is very deep if you look at the lyrics.

“But I love that people buy the

record and enjoy it because it just sounds beautiful. And then there are these

layers you can discover later.”

Discovering more about Gurrumul himself

is harder. He doesn't give interviews and rarely speaks in English, so

Hohnen has been his spokesman.

“He's shy and he's not confident with

his English in public, but it's a lot more than that. His uncle talks

of him being ashamed of his blindness. What I read into that, having

spent a lot of time thinking about and experiencing it, is that

Gurrumul never sees how people react to what he says. He feels it,

but never sees it.

“He's also grown up with consummate [English] speakers and people whose roles are to be the leaders and speakers.

His role has never been that in either Aboriginal or English-speaking

society. His role is to be a song person to take their music and

songs out there . . . and not go and talk about, 'How you feel and how the

government is treating us'.

“He's also grown up with consummate [English] speakers and people whose roles are to be the leaders and speakers.

His role has never been that in either Aboriginal or English-speaking

society. His role is to be a song person to take their music and

songs out there . . . and not go and talk about, 'How you feel and how the

government is treating us'.

“I'm comfortable about my position now," says Hohnen "because I speak about him and how I see how he fits in to everything, rather than speaking for him.

"I don't ever pretend to

answer questions which are for him.

“He knows a lot of English words but

would struggle in any discussion that starts to become slightly

intellectual, but that's only because of the language. Because they

way we think is completely different from the way the Yolnu [people]

think.”

Hohnen knows this world as well as any

and has spent 15 years working with Gurrumul, a full decade of that before Gurrumul's breathtaking debut album. But Hohnen's background is also in the

mainstream pop world.

He spent his younger years in

Melbourne, played in bands in Australia and Europe (notably the

Killjoys who were “big in the indie pop scene and did reasonably

well in UK and Europe where we did some recording”) and also had

some experience in classical music and jazz.

But increasingly he became

disillusioned: “I love Western music and pop but I hit this point

where it all started to be the same in its sentiment. It was

middle-class white – which is what I felt – and a lot of the

bands I was involved in were like a social experiment which ended up as a band . . . quite self-indulgent and not that meaningful.”

He met some Aboriginal musicians, moved

to Darwin where -- through the university's TAFT programme -- he ran

vocational training courses on the music industry which took him to

remote places like Elcho.

The community there had produced a

number of musicians, some of whom were in the Warumpi Band and Yothu

Yindi, and there had been regular requests from the island for assistance in

music programmes.

It was there in '96 Hohnen met Gurrumul

who had spent seven years in Yothu Yindi until '94 and

was now back home.

“He was not a pro-active member [of Yothu Yindi] but

because of his talents was very engaged on a musical level. He wrote

the piano riff on Treaty which was a really big hit in Australia and

he's all over their Tribal Voice album.”

Hohnen didn't know of Gurrumul's

reputation at this point, but some of his Elcho peers presented him to Hohnen one day

saying they thought he [Hohnen] might like him.

“I thought he was far more talented

than the other guys, but I was educated at the Victorian College of

the Arts and coming from a place like that of high standards of musicianship, I didn't immediately see it. I remember him doing some things

after hours and I heard the way he sang and multi-tracked the

guitars. And he was blind. It all added up to something significant.

“He does have an aura or some special

energy and people feel that straight away, and it doesn't matter if

you are a spiritual person or not even interested in that. Most

people who meet him are immediately struck and engaged by him.

“He does have an aura or some special

energy and people feel that straight away, and it doesn't matter if

you are a spiritual person or not even interested in that. Most

people who meet him are immediately struck and engaged by him.

"So

there was a bit of that going on too.”

Out of Hohnen's time on the island the

Saltwater Band was formed – a 10-piece which included Gurrumul –

but it became increasingly obvious who the real talent was: the blind

guy who would sing, multi-track all the parts and arrange the music.

“With the Saltwater Band, I wasn't

there as an A&R person looking for talent, I just helped them on

their first and second records. But on the second I started to

wonder, 'Why don't more people know about him?' “

Hohnen suggested to Gurrumul that maybe they try just some acoustic recordings.

“He'd had a couple of big

apprenticeships with Yothu Yindi and Saltwater, so it wasn't like he

was new to the game.”

And because Hohnen had been around the local people and Gurrumul's family for a decade, a trust had built up. When he said thing would

happen they usually did, which is not always the way in Aboriginal people's

dealing with white fellas.

“There are a lot of [white] people coming

through communities here who come and go. But Mark [Grose] and I who

started the Skinnyfish label, we're still here and not part of that

transient population of white fellas.

“Mark lives at Elcho Island now so

has day-to-day contact with Gurrumul and his family and the musicians

around him. So the trust was enough for Gurrumul to say he would try

something with me. So we did a couple of acoustic things in Darwin and

everyone was highly responsive.”

Hohnen says having heard the Jose

Gonzalez album Veneer and how simple it was – “nylon string

guitar, double tracked vocals, just simple and universal and

touching, even though people didn't understand everything he was

saying” – gave him encouragement.

He and Gurrumul relocated to Melbourne to record

and tried out a number of different songs and styles, some more

uptempo “just to open everything up so people could hear his

voice”.

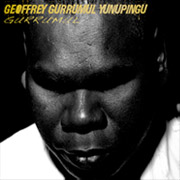

Skinnyfish also presented the debut

album in a handsome package with a booklet . . . and in a cover which

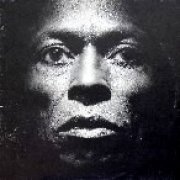

also almost mimicked Miles Davis' striking Tutu

cover by photographer Irving Penn?

Skinnyfish also presented the debut

album in a handsome package with a booklet . . . and in a cover which

also almost mimicked Miles Davis' striking Tutu

cover by photographer Irving Penn?

“Well, you got the Miles Davis reference,” he laughs, “because I did want that kind of striking image but didn't want to copy Tutu.

"Well done. I have done a lot of interviews about Gurrumul and thought that could have come up, but you are the first to get it.

“I got a photographer and we looked

at Tutu and I said I wanted that energy, but Gurrumul is a very

different person. Miles is very in your face and he is not. So that

is what we went for.”

“I got a photographer and we looked

at Tutu and I said I wanted that energy, but Gurrumul is a very

different person. Miles is very in your face and he is not. So that

is what we went for.”

Hohnen says as a small label Skinnyfish were not geared up for mainstream success and nor was that ever their aim: “We're not commercial in a sense, we were set up to support artists and

realise the visions of musicians -- and not a lot of those visions

are commercial. They are about story-telling, community and are experiential. But when I made the [Gurrumul] record I thought it was special.”

The company also hired a PR person -- a first for them -- and

over six to eight months the momentum grew behind the album. By the

time Gurrumul was invited to play at the '08 Aria awards in Australia the album had

gone gold.

“He's very grounded and we are very

realistic. It wasn't like, 'Great, let's start partying'. I've been

involved with lots of bands and the first bit of success . . . it's a

non-stop party until they run out of money.

“This was more like, 'Okay, we have

to manufacture more, we have to think about this properly'. But it

also changed Gurrumul's life, and our lives.”

Hohnen says, as is common among

successful Aboriginal artists of all persuasions, much of Gurrumul's

money goes back into his community and is “disseminated”.

“He's not very materialistic and

that's not a big factor in terms of changing anything. A lot of

people don't believe him when he says he hasn't got money, but what I

have witnessed is he tries to get rid of it as quickly as possible.

“I bought him a t-shirt the other day

which a take on the Mastercard symbol but it says 'Broke' and he

loves that.”

“I bought him a t-shirt the other day

which a take on the Mastercard symbol but it says 'Broke' and he

loves that.”

Not that getting the album away in Europe was easy.

While the world music magazine Songlines put

Gurrumul on the cover, Hohnen notes there is “a world music police

out there in some places”.

“There's this world music scene that exists, especially in Europe, and it kind of dictates what world music is, and concentrates on French-African bands. That scene has ignored Gurrumul. One [magazine] wrote back saying he was not Aboriginal enough.”

No didgeridoo, perhaps?

Hohnen also says many of the world

music festivals are based around jamming bands so an artist like

Gurrumul who sits and plays guitar quietly doesn't fit in that

situation either. Although they have played some of these festivals,

sound bleeding from other stages works against Gurrumul and this special music which Gurrumul's mother describes as “sacred”.

“I think she's referring to publicly

sacred, something that is incredibly important to them and is the

essence of who they are. Because in their culture there is sacred and

almost secret, a ceremony which exists only within that culture.

“I think she's referring to publicly

sacred, something that is incredibly important to them and is the

essence of who they are. Because in their culture there is sacred and

almost secret, a ceremony which exists only within that culture.

“He is singing about something that

embodies him and her, and the essence of their identity. It is

important and personal and all about identity.”

This is why in

the new Rrakala album there are some notes explaining the songs and

their cultural context.

“However unless you have a treatise or some

big booklet, you don't get very far into the meanings of the words. But I did ask some of the guys working with him to summarise the songs in a paragraph – which gives you a completely different

interpretation of the songs from the direct translation,” he

laughs.

“When people like Gurrumul talk about

themselves they talk about who they are and their relationship with

everyone else. And if you keep asking the talk will go into their

relationship with trees and animals in their world.

“So they are part of the bigger

picture from the word 'Go' and the whole structure of life."

“So they are part of the bigger

picture from the word 'Go' and the whole structure of life."

And of that other real world he

inhabits, that of culture and commerce and record sales, Gurrumul

remains amusingly detached.

Hohnen says he sees it his duty to keep

his friend informed, but often when he's reading him some article or

interview to him Gurrumul will interrupt and ask about something mundane.

He's not really listening.

“In a sense he doesn't know how

successful he is. He's got a good feeling because people tell him. But he doesn't know about the charts or sales.

“I'm constantly banging on about what is happening in the charts and he still asks what that means.

"Like he'll say, 'Number three? Out of how many?' "

Interested in more on Aboriginal art and culture? Then try here and here. And this is also important.

Jamie - May 27, 2011

A really nice article Graham, thank you.

SaveThrough your review I bought and loved the first album and gave a cluster of them away as Christmas presents.

I had often wondered how such a modest retiring man had achieved the success and breadth of exposure that he has. I hadn't heard about the relationship between him and Michael Hohnen.

What a cool story! I love this man Michael! How exciting for both of them that they met, and that Michael had the dedication and belief to hang in there and see the project through.

So often the stories of people like Michael must go unsung, so to speak. The role they play in bringing remarkable, humble, introverted musicians to a wide audience deserves shouting out from the roof tops! Bono doesn't need a Michael Hohnen, but the extraordinary Gurrumul, and so many others like him, do.

Cool story, well told. I feel inspired!

post a comment