Graham Reid | | 12 min read

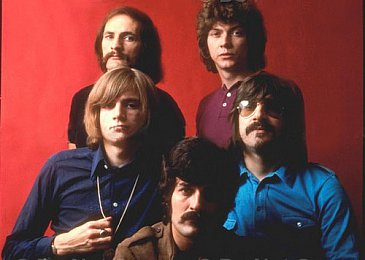

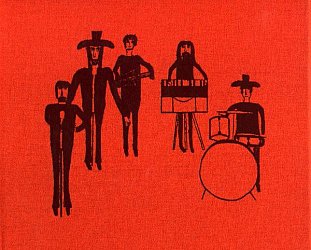

The Moody Blues: Legend of a Mind

In the late Sixties, when the boundaries of pop and rock were being extended into jazz and quasi-classical areas, the Moody Blues were one of the most musically innovative and productive groups of the period.

Their albums between Days

of Future Passed in 67 and Seventh

Sojourn in 72 – an extraordinary seven albums in five years

following their hit single Nights in

White Satin – anticipated the prog-rock which followed.

But the Moody Blues – in which all

five members wrote – managed to deliver albums of self-contained

songs without the bloating which marked much prog.

Theirs was a kind of symphonic pop

(Days of Future Passed was with cobbled together classical players

performing as the London Festival Orchestra) and many of these early

records – on which they played an astonishing array of instruments

from flute to sitar and with Mike Pinder on mellotron, an instrument he

apparently introduced to Paul McCartney and John Lennon -- were

loosely concept albums . . . but not so much that they were constrained by

any narrative. They were orchestrated psychedelic pop albums which

sprang singles.

The Moody Blues also enjoyed a rare

association with a single producer, much as the Beatles had done with

George Martin. They had Decca's in-house Tony Clarke (often credited

as the sixth Moody with his photo on the cover) and in 69 – a year

after the Beatles launched their Apple label -- they started

Threshold Records to keep creative control of their work, before

bands like the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin would do.

The Moody Blues also enjoyed a rare

association with a single producer, much as the Beatles had done with

George Martin. They had Decca's in-house Tony Clarke (often credited

as the sixth Moody with his photo on the cover) and in 69 – a year

after the Beatles launched their Apple label -- they started

Threshold Records to keep creative control of their work, before

bands like the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin would do.

In

many ways they were in the vanguard of the modern musical landscape

but singer/guitarist Justin Hayward – who also pursued a successful solo career

and sang in Jeff

Wayne's War of the Worlds

– admits they were lucky.

Speaking from his sister's house in

Cornwell – “four seasons in one day here” – he initially

jokes about his bit part in War of the Worlds.

“I enjoy it anyway because there's no

pressure for me. I just have to get into my 1890s costume and sing

songs and not trip over the furniture while I sing.”

A gentleman's gig then?

“That's a very good way of putting

it, I like that. Exactly”

The Moody Blues recorded a remarkable

seven albums in a little over five years. That makes today's young

musicians seem rather lazy.

The Moody Blues recorded a remarkable

seven albums in a little over five years. That makes today's young

musicians seem rather lazy.

We were very lucky to have a great

record company which paid us a pittance in royalties but had

wonderful recording studios and all they wanted us to do, after Days

of Future Passed and they had success with that as an album, was just

keep on making records and work as much as we could in the studios.

It was a wonderful time and I loved every minute of it.

Then we went to America and were taken

there by [promoter] Bill Graham and arrived at the beginning of FM

radio taking off in the US and our stuff was just perfect for it.

You wrote Nights in White Satin when

you were just 19?

Yes, but I'd started young and felt I

was ready for that and everything fell into place around that year.

I'd written a lot of songs before that and came to the band as a

songwriter. But it wasn't until Mike [Pinder] found the mellotron

that my songs really seemed to work.

Before that I was trying to fit them

into some kind of r'n'b format with a piano or a Vox Continental

organ.

But Mike had heard of this instrument

and had seen in Dunlop's, a club in Birmingham and they wanted to

sell and only wanted 20 pounds for it. So we brought it back in the

van and took out all the sound effects bits, because it was a sound

effects instrument really, and just duplicated with great difficulty

all the orchestral parts.

And even though it was incredibly

unreliable it did have an amazing sound and it made my songs work,

and that's why there was that flowering around that time.

I wasn't the youngest on the scene

though, Stevie Winwood was a year younger than me. Everyone seemed to

start early then and I was very lucky to be a professional musician

since I left school.

I worked in an office for about two months and

then got a job with Marty Wilde and that was baptism of fire into

the world of professional music.

I worked in an office for about two months and

then got a job with Marty Wilde and that was baptism of fire into

the world of professional music.

That was an honour and privilege, I was

in awe of him and I still am. I often go back to those days and think

about him. Also he's 6'5" and I'm 6'2" so I spent a couple of

years looking up to somebody, which for me was very unusual.

With Oh Boy and television shows like that it was

50:50 between Marty and Cliff Richard, and Cliff quite rightly became

the sort of British Elvis rock'n'roll idol. I think Cliff made the

only British rock'n'roll song at the time with Move It.

The Moody Blues had that rare long-term

relationship with a producer, Tony Clarke.

Tony was a big part of it and was often

called the sixth Moody Blue and we put his photo on the covers, he

was more than just an independent producer. He was assigned to us by

Decca for one our songs Fly Me High and Gus Dudgeon was the engineer.

They both did a great job and he was the kind of producer who was the

opposite to others I've met like Tony Visconti whom I've worked with.

Tony Visconti is very practical, very

hands on and if you don't know how to do something he'll make it work

and he'll have the right little machine to put things in tune and

he'll do it himself. Whereas Tony Clarke could do none of that but

could sit back and see the whole album as a movie in front of him,

and he talked in that esoteric way about what we should be feeling

and what should come through.

I'm quite practical and they usually

relied on me for a song to start an album, so that attitude would

inspire me and I'd try to make it happen, almost to make Tony happy

because if Tony was happy things were wonderful.

You personally had songs like Question

which were successful singles, unlike many of the later prog-rock

bands. You'd often release a single just before and album, I guess

because you knew pop culture?

You personally had songs like Question

which were successful singles, unlike many of the later prog-rock

bands. You'd often release a single just before and album, I guess

because you knew pop culture?

Singles were always seen as the

promotional tool and what we didn't want to do was make any singles

which followed any trend or pattern. So we were the bane of the A&R

guys' lives because we delivered stuff that wasn't single material

and wasn't 2'57” long. But they would be representative of what the

album was all about, and that was what concerned us most.

We didn't have many great singles and

it wasn't until the Eighties until we had a sort of singles explosion

with two big singles, one was Wildest Dreams and the other was I Know

You're Out There Somewhere.

To have to a record in the charts

sounding like really well made singles, and done by Tony Visconti who

beautifully produced those albums, was wonderful for us. I was in my

early 40s and to have success again and be recognised in the street

as the guy in the video, and to have everybody love the record and to

hear it everywhere you went , was a great experience.

I'd missed it first time around with

Question and those things because I was too busy or too ambitious,

and probably too stoned as well. But the second time around in the

Eighties I savoured every moment.

You missed it?

Yes. Particularly before 1974 when we

went our own way because royalties took a long to arrive and we were

on a small royalty anyway so we weren't as rich as other bands . . .

even though we were selling a lot of albums. Singles success probably

does earn you more than album success, but it took us a long time to

develop a lifestyle because we were on the road so much and recording

so much that we just didn't notice it.

There are milestones in your life, like

buying a house and you still have to worry how you are going to pay a

25 year mortgage, and we played Madison Square Garden twice in the

same day in about 72 and it dawned on us that this was quite amazing.

We were walking around outside and we saw we'd sold out twice. They

gave us the award of the Golden Ticket. Everybody could sell it out

once, but twice? I've still got that award at home. It took us that

long to realise we were having success.

So that is in your trophy room?

No, there's trophy room. I've downsized

and I live near near the Italian border in the south of France in a

small place, but a few years ago I photographed a lot of that stuff,

but I don't know what's happened to all that stuff.

That sounds a lovely place to live, and

not really surprising to me. In 1979 Chris Welch of the NME

interviewed you all and observed there was something “unhurried and

quiet” about the band, although he did note Ray Thomas was the

exception.

That sounds a lovely place to live, and

not really surprising to me. In 1979 Chris Welch of the NME

interviewed you all and observed there was something “unhurried and

quiet” about the band, although he did note Ray Thomas was the

exception.

Yes, very much so. We were very, very lucky to have

people around us who concentrated on the music and not us as

celebrities, but I think we chose that in the early days also. I

don't think we even smiled on a photograph until about 1979.

There was a feeling in the band in the

first few years that we were doing something arty. There wasn't a

snobbery about it and our personal ambitions weren't high really, we

just wanted to play the music and get on with it and immerse

ourselves in it. It's only later that you start to come out of that

shell when publicists demand you go on morning television and you

have to accept you have to play your part and promote the stuff in

that way.

In the early days we didn't just the

occasional television show which is why, sadly, there is a lack of

early film of the Moody Blues, although a few things have turned up

on You Tube.

There's a very funny one of Nights in

White Satin with you on a staircase, two of you singing and the other

guys just standing mute and looking bored in the background.

Yes, Graeme [Edge] standing there like, 'What

the fucking hell is going on?' It was very early one morning in

Germany with a dodgy tummy after the night before.

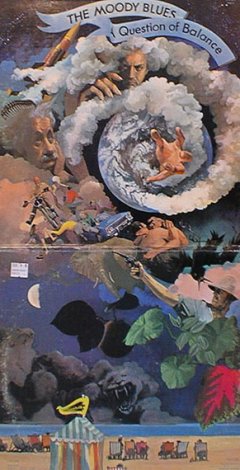

You also had a rare relationship with

your cover artist Phil Travers also which anticipated Yes'

relationship with the artist Roger Deans. You were very much ahead of

the game.

You also had a rare relationship with

your cover artist Phil Travers also which anticipated Yes'

relationship with the artist Roger Deans. You were very much ahead of

the game.

I do think that, yes. We've been lumped

in with other band but they came after us and it was three or four

years before anyone started calling it prog-rock or classic rock.

That's okay, but the sleeves were very important to us, and to find

Phil Travers – who was the staff artist at Decca – and his stuff

was just wonderful.

We'd invite him to the studio for a day

and he'd just be around and he'd make sketches and when the album was

finished he'd be finished with the sleeve as well.

He'd somehow tie

up all he elements that we'd been singing and talking about. We had

to take an even lower royalty to have those sleeves because it was

important to us that we should have gatefold stuff.

One of the sleeves we got sued for,

which was a bit sad. I've got the original at home which is very very

large. It is the original painting for A Question of Balance. There's

a man, a white hunter you might call him, pointing a gun at an

elephant's head.

I'm looking at it right now.

Does he have a black mark across his

face?

Not on mine. Oh, that must be a real original then.

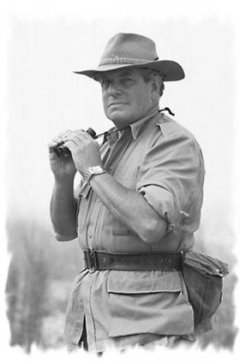

That man was Major Blashford-Snell who was quite a hero in those days

and he appeared on stage one night and served a writ saying that we'd

stolen his image. We just thought that was nonsense and that Phil had

just made it up out of his head until I gave Phil a call and asked

him if he'd copied that picture. And he said, 'Ah, as a matter of

fact I did, I just find these things in newspapers and just copy them

if they look good.'

Oh, that must be a real original then.

That man was Major Blashford-Snell who was quite a hero in those days

and he appeared on stage one night and served a writ saying that we'd

stolen his image. We just thought that was nonsense and that Phil had

just made it up out of his head until I gave Phil a call and asked

him if he'd copied that picture. And he said, 'Ah, as a matter of

fact I did, I just find these things in newspapers and just copy them

if they look good.'

I said, 'He wasn't shooting an elephant

though' and Phil said, 'No but he was holding gun'. So we had to make

rather a large settlement with Major Blashford-Snell and promise to

put a black strip across his eyes immediately, and after that Phil

had to redraw him so it wouldn't look like him. He didn't like what

we were suggesting he was doing, which he probably was!

The band still seems very busy so I am

guessing life is good for you.

It's very busy, we are offered so much

work now that we could be on the road 365 days a year and that's a

curious thing, we seem to be a bread and butter band for a lot of

promoters. I'm not complaining, but we seem to be on the road maybe

six or seven months a year, which is a lot. But I enjoy and to be in

a band that does my stuff great is all I ever wanted. There's only the three of us now –

me, Graeme and John Lodge – but the other people we have are wonderful.

Nora Mullen on flute is divine and before she came to us she was with

the LA Symphony and knew all our stuff, she'd been brought up with it

and knew it better than I did. So the people around us make it even

more special.

There's only the three of us now –

me, Graeme and John Lodge – but the other people we have are wonderful.

Nora Mullen on flute is divine and before she came to us she was with

the LA Symphony and knew all our stuff, she'd been brought up with it

and knew it better than I did. So the people around us make it even

more special.

You couldn't do this stuff on stage

properly back in the early Seventies, but technology catches up and

now you can replicate the complex sounds.

Yes, we use Julie Ragins who has a

perfect harmony voice and we also have the memotron now which is the

perfect digital copy of the Mellotron and the sound is exactly the

same. So we are truer to the records now than we ever were in the

Seventies, and of course there was a revolution in acoustic guitar

pick-ups so I can do that on stage and it will be heard, and with

exactly the right balance too.

It's always a question of balance isn't

it?

Yes, (laughs). Oh very good.

post a comment