Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Bo Diddley: Another Sugar Daddy

In 2002 after a Rolling Stones concert in Chicago I asked my friend, who lived in the city, to take me down to 2120 South Michigan Avenue, the old home of Chess Records.

Aside from wanting to see this legendary place where Howlin' Wolf, Bo Diddley, Etta James, Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon once held court, I also half thought that Mick'n'Keith'n'Charlie might drop by.

After all, it was the music from this studio which gave them a foundation as a young blues band in Britain, where they also recorded most of their second album 12 X 5, and had one instrumental track entitled 2120 South Michigan Avenue by way of tribute.

Of course they didn't turn up but it hardly mattered. I was there and stood on what was once known as Record Row where all the giants had walked, many of them hustling their songs in the coffee shops which used to be along here.

Chess had long since moved on -- one of the founders Leonard Chess died in '69 and shortly thereafter the label was sold -- but Willie Dixon's widow had taken the place over and had had it renovated.

I didn't get inside -- that's for another trip -- but Chess looms large in many people's lives as where some of the greatest and most tough urban blues came from, the music which inspired a generation in the early Sixties . . . although to be fair those songs don't appear to have quite as much influence today.

Not for want of well-intentioned people trying however.

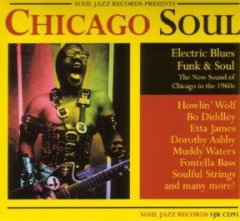

MCA did decent CD box sets of Wolf, Willie, Bo Diddley, Chuck and Muddy in the late Eighties, and in 2004 the Soul Jazz label presented the 20 track album Chicago Soul: Electric Blues Funk and Soul, subtitled Chess Records; The New Sound of Chicago in the 1960s.

This collection -- with an informative 40 page booklet of the story behind the label and its seminal artists -- has been re-presented to coincide with various BBC docos about Chess.

This collection -- with an informative 40 page booklet of the story behind the label and its seminal artists -- has been re-presented to coincide with various BBC docos about Chess.

It wraps up many facets of Chess from the earthiness of Howlin' Wolf's Evil and Bo Diddley's darkly angry Another Sugar Daddy (which you could imagine the Stones covering, the phrasing is very Jagger) through to the Caribbean soul-funk of piano player Ramsey Lewis' Party Time to the psychedelic dance of Dorothy Ashby's Soul Vibration.

And beyond.

The free-wheeling, non-chronological approach let's you hear Chess as something beyond a blues label, a company like any other looking for new talent which could connect to the changing tenor and tremors of the volatile times.

There is highly charged politics here (Gene Chandler's tough, horn-punched In My Body's House, written by Curtis Mayfield) but also soaring soul (Fontella Bass with the Motown-styled Leave It In the Hands of Love) and I Just Want to Make Love to You from Muddy Water's '68 makeover as a psychedelic bluesman on the album Electric Mud with Phil Upchurch going the whole kiss-the-sky route.

There are rare grooves -- the Stereos' funkdown on Stereo Freeze, Eve Barnum's Please Newsboy from '69 where the strings seem to anticipate disco -- and trippy cool jazz (the Soulful Strings' Burning Spear with flittery flute).

Buddy Guy gets down'n'funky on She Suits Me to a Tee.

Hoagy Carmicheal's Baltimore Oriole gets a sultry and sassy treatment from Lorez Alexandria.

It's an odd one.

So is the Rotary Connection's Memory Band. Some very stoned people in the studio that day, perhaps.

So this collection pulls the image of Chess away from that of Sonny Boy Williamson (right) in a shouting match with Leonard Chess.

So this collection pulls the image of Chess away from that of Sonny Boy Williamson (right) in a shouting match with Leonard Chess.

Or that Keith Richards story about arriving at the studio for the first time and seeing Muddy Waters up a ladder painting the ceiling (which is not true according to the reliable Bill Wyman).

Chess recorded some of the greatest blues and early rock'n'roll artists, but that is only part of the story.

This is another chapter which is just as interesting, if rather more diverse.

For more on Chicago blues try this and this. There is more on Chess Records here.

And this

post a comment