Graham Reid | | 6 min read

The guitarist G. E. Smith must have great stories to tell. For a little over two years in the late 80s he was, for want a better description, Bob Dylan's band leader.

During those difficult years when Dylan was emotionally adrift, Smith would audition players and introduce them to a repertoire of well over 100 songs, and replace members as some inevitably dropped out or Dylan would obliquely suggest he wanted someone gone.

Before the shows it was often Smith's job to tell the band Dylan had changed the set list and was now going to play something they hadn't rehearsed, or some old folk tune they'd never heard of. On stage, Smith would have to communicate to band members what the boss wanted because Dylan would seldom talk to the musicians on or off stage.

It wasn't uncommon for Dylan to turn to Smith before playing Like A Rolling Stone or some other classic from his scrapbook of genius and whisper an instruction such as, "in reggae style."

Bob Dylan, legend that he might be, must be one awkward cuss to work with.

Slash, the guitarist from Guns N' Roses, who played with Dylan on the Under the Red Sky sessions in 90 when the singer was in the habit of wearing a hooded jacket and often performed on stage in almost total darkness, said, "Even when he was talking to me, all I could see behind all those hoods and the shades was his nose and his upper lip."

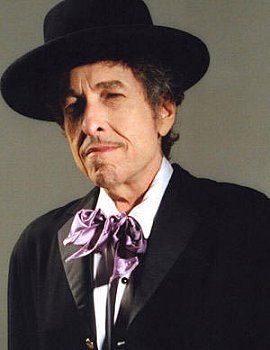

After 40 years, Dylan is no more penetrable or easy to figure.

Since he emerged in the early 60s Dylan has been a strange one, a man who made his own rules, would change musical direction abruptly and most often hide behind his elusiveness and shades.

On Thursday Bob Dylan - born Robert Allen Zimmerman in the small town of Duluth in Minnesota near the Canadian border and descended from East European Jewish immigrants - will turn 60.

He has outlived those who influenced him - folk singer Woody Guthrie, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg - and outlasted those whose music and attitudes he changed, like John Lennon. Many of those down the decades hailed as "the new Dylan" have fallen by the wayside. And Bob just carries on and on.

Yet, despite the thousands of words spilled in interpretation, analysis and biography, he remains a mysterious figure, a man who even now lives on the road, playing an extraordinary number of concerts every year.

Why does he continue to do it? Some suggest it's because it is the only life he has known, others say it's because as an outlaw he knows a moving target is harder to hit.

Dylan himself, in a rare interview, once observed, "An easy way out would be to say, Yeah, it's all behind me, that's it and there is no more. But you want to say there might be a small chance that something up there will surpass whatever you did. Everyone works in the shadow of what they've previously done. But you have to overcome that."

And few work in a bigger shadow than Dylan, who redefined the parameters of popular music at least three times: when he married a literary sensibility to folk in the early 60s; when he plugged in an electric guitar and brought new heights of personal and poetic consciousness to rock in the mid 60s; and throughout the decades as he explored traditional folk, blues and religious or philosophical imagery within the context of rock culture.

And always, just when he was being marginalised by the music world he helped to create, he would reinvigorate himself and his music. (See sidebar.)

And he's never been easy to figure.

"Bob was different," his first girlfriend Echo Helstrom once said, "Mostly he withdrew inside himself, a silent kind of rebellion."

So in the boy we see the man.

From the beginning Dylan played games with those who try to define him. In the early 60s he created his own self-mythologising biography: "Hibbing's a good old town," he wrote in My Life in a Stolen Moment about the place he was schooled. "I ran away from it when I was 10, 12, 13, 15, 15 1/2, 17 an' 18. I been caught an' brought back all but once." It wasn't true.

He also famously commented that he was "a mathematical kind of singer" and was just "a song-and-dance man." Not true either.

An intensely private man - his roster of girlfriends and partners remains a secret - he said 10 years ago, "People can learn everything about me through my songs, if they know where to look." True perhaps, but where to look?

His most recent song, Things Have Changed, contains the telling line, "I've been trying to get as far away from myself as I can." Is that helpful? Not really, because in the same song he also says, "Gonna take dancing lessons, do the jitterbug rag, ain't no shortcut, gonna dress in drag." Hmmm.

There are websites which interpret his lyrics using Judaic imagery (Tangled Up in Jews), the Kabbalah and the Bible. He throws false trails and always keeps moving, which is what makes him a unique character in contemporary music.

What Dylan has become is a troubadour, an itinerant poet taking his music to wherever it might be wanted. It's a rare calling and an idea he doubtless inherited from Guthrie's peripatetic lifestyle which he married to his love of the French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine.

Is he an enigma? At one level, but not giving interviews is often interpreted as being mysterious. No, he just doesn't do that stuff.

He hasn't been precious about his gifts, however. He plays in rundown halls and basketball stadiums, small rooms and at huge outdoor festivals and has been a spendthrift of his genius.

His shows can be punctuated by appalling jokes ("He must have thought he was playing golf today," he typically quipped about one band member, "because he wore two shirts in case he got a hole in one.") and he is no respecter of his own songs. He will constantly change them, sometimes for the worse. Many here will recall his Supertop concert of 92 when he appeared unable to tell one end of the harmonica from another.

He's sometimes been the absentee landlord of his own songs.

That said, he changed the lexicon and possibilities of popular music forever, offered the Beatles an option beyond pop songs, and prepared the ground for people like Lou Reed and Patti Smith. His back catalogue is a constant revelation, and he is unquestionably a singular figure in music today.

More than any other artist, Dylan has had his lyrics quoted back at him and found them included in collections of contemporary quotations.

There is only one Bob Dylan ... whoever that might be.

Long may he ramble, irritating or illuminating from the concert stage.

Happy birthday, Bob. What a long, strange, enigmatic, frustrating and enjoyable trip it has been.

post a comment