Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Pink Floyd: Sheep (extract)

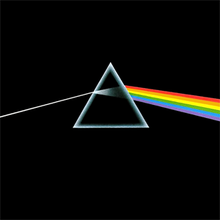

Despite the textual analysis possible on Wish You Were Here in 1975 and the gargantuan theatrics of The Wall (a largely unlistenable album and often as dull as its cover), it is always The Dark Side of the Moon where the Pink Floyd story pivots.

That album -- 50 million sold, in the Billboard top 200 for more than 14 years after its release in March '73 -- captured the uneasiness of the post-hippie era in songs about fragile sanity, the pressures of work and the money trap, and some quasi mystical stuff which was neatly undermined by taut musicianship and a voice at the end which says, "there is no dark side of the moon".

Just six songs and some instrumental interludes and sound collages, it was also recorded at Abbey Road using the pinnacle of studio technology at the time and the band -- fresh off Meddle which guitarist David Gilmour especially liked as its side-long Echoes pointed a direction out of their creative roadblock -- was previewed in concerts before they hit the studio in earnest.

Just six songs and some instrumental interludes and sound collages, it was also recorded at Abbey Road using the pinnacle of studio technology at the time and the band -- fresh off Meddle which guitarist David Gilmour especially liked as its side-long Echoes pointed a direction out of their creative roadblock -- was previewed in concerts before they hit the studio in earnest.

All the stars were aligned for an album which was polished, sometimes soulful, often brittle with intensity and yet allowed for some emotional relief and release in various places.

Little wonder then it was hailed as a milestone.

Needless to say there are those could not hate it more, but you suspect in many instances that position is rather more to do with scale of its success and how it is emblematic of an era and style than any inherent failings of the album itself.

Dark Side became a cipher for all the inflated, self-important and over-blown prog-rock which followed, some of it from Pink Floyd itself.

The 2011 remastered versions -- notably the Immersion Edition with previously unreleased tracks and different mixes -- provide insights into how it was constructed. There is Waters' acoustic home demo of Money (hear it here) among the extra tracks.

The Great Gig in the Sky version without the soulful vocals of Clare Torry comes as a real surprise -- it is rather lovely by being less emotionally overwrought -- and a reminder that absence can make as much an impact as presence.

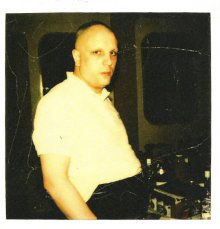

It was absence which prompted Wish You Were Here in '75, the absence of former member Syd Barrett who turned up in the studio unannounced and unrecognisable during the sessions. In his book Inside Out, Nick Mason said he noticed "a large fat bloke with a shaven head, wearing a decrepit old tan mac" and he assumed it was a friend of the engineers.

David Gilmour asked Mason if he knew who it was and the drummer said he didn't. When told it was Barrett he was "horrified by the physical change. I still had a vision of the character I had last seen seven years earlier, six stone lighter, with dark curly hair and an ebullient personality".

David Gilmour asked Mason if he knew who it was and the drummer said he didn't. When told it was Barrett he was "horrified by the physical change. I still had a vision of the character I had last seen seven years earlier, six stone lighter, with dark curly hair and an ebullient personality".

It sounds a disconcerting encounter (contrary to rumour it seems Barrett wasn't there for the playback of Shine On You Crazy Diamond, of which he was the subject) and although most of the Barrett-related lyrics had been written by this time Mason says his appearance underscored their melancholy.

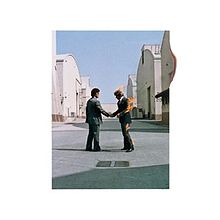

Wish You Were Here (consistently voted their favourite Pink Floyd album by fans) confirmed that Roger Waters -- who the others acknowledge was coming up with more ideas and the themes of their albums -- was now firmly at the helm of the group and his cynicism about the music business was evident in material like Welcome to the Machine and Have a Cigar (sung by Roy Harper).

It was an acerbic and bitter trait he would extend into subsequent albums where he held even tighter onto the creative direction of the band.

Wish You Were Here opens with a lengthy instrumental passage which had been developed, largely by Gilmour, at rehearsals and shows (and includes elements of their earlier Household Objects jam session/experiments, some of which are included on the Dark Side Immersion disc set). It also bookends the album as the multiple-part Shine On You Crazy Diamond suite (about Barrett).

Wish You Were Here opens with a lengthy instrumental passage which had been developed, largely by Gilmour, at rehearsals and shows (and includes elements of their earlier Household Objects jam session/experiments, some of which are included on the Dark Side Immersion disc set). It also bookends the album as the multiple-part Shine On You Crazy Diamond suite (about Barrett).

Although both Gilmour and keyboard player Rick Wright like the album, at the time it met with considerable critical disapproval for its lack of emotional bite (given the subjects were dear to their hearts) although no one denied the sheer professionalism of its instrumental sheen.

Even though it only sold about a third of Dark Side, it remains one of the most popular albums in the Floyd catalogue, although that might be for the nodding nostalgia value of its subject matter and more stories about poor Syd.

But it confirmed that Floyd were a band of more than one classic album and this one has weathered rather better than the many which followed. It sounds terrific in the remastering.

As has been noted by using Radiohead for the analogy, if Dark Side of the Moon was Floyd's OK Computer, then this was their Kid A. The great headphones album -- and boosted by arguably Gilmour's finest and most consistent guitar work which is the glue holding the concept and separate threads together.

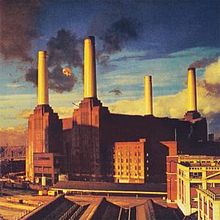

Animals in '77 -- released two months after the Sex Pistols' Anarchy in the UK -- was the Floyd album which, in theory, should have most appeal in the punk era: Waters' themes of an alienating social breakdown in Britain were not too far removed from the nihilism and anarchic tendencies of the period, although it seems Waters already had much of the material written before the Sex Pistols hit the headlines and frontlines.

Animals in '77 -- released two months after the Sex Pistols' Anarchy in the UK -- was the Floyd album which, in theory, should have most appeal in the punk era: Waters' themes of an alienating social breakdown in Britain were not too far removed from the nihilism and anarchic tendencies of the period, although it seems Waters already had much of the material written before the Sex Pistols hit the headlines and frontlines.

Some of the songs (in different versions) had even been played live as far back as '74.

It is a dour, bleak and earnest album ("unpleasant" according to Mojo) and was the first signs of the real inner tensions within Floyd: Wright was increasingly marginalised by Waters, the publishing credits became an issue because Waters' piece Pigs was split in two to bracket the album (therefore giving him two bites of publishing royalties) and while Mason says he thought the recording was enjoyable and straightforward Wright recalled arguments.

It isn't an easy album, nor an especially interesting one in many ways and the concept is thin and strained, and material like the 17 minutes Dogs sounds padded by Gilmour's signature guitar.

When the tour started Waters -- who by now felt he was carrying much of the creative weight on albums -- would travel to the venues by himself, and Gilmour felt they were now too huge to connect with their audience. True, the props were starting to gain as much attention as the music.

It was at a show in July '77 that Waters, enraged by fans baying from the front row, spat at one of them, had something of an epiphany and later spoke of wanting to build a wall between the band and their audience.

So . . .

So . . .

The Wall and the good news first?

One of the three producers Bob Ezrin (alongside Waters and Gilmour) said that while there was a gentlemanly English war going on during the sessions -- that is, Waters and Gilmour being sarcastic, cutting and condescending towards each other, but always politely and in considered language -- that album really is quite something.

More than that in fact.

"Everybody was going through amazing stuff in their individual lives, and we all brought our pain and weakness and our foibles and our peculiarities to the table.

"But in the final analysis it produced what is arguably the best work of that decade and maybe one of the most important rock albums ever made."

Let's ignore the hedge-betting "arguably" and "maybe" there.

If The Wall was a zenith then it is speaks of a blighted, urban landscape of betrayed dreams, disillution, contempt (of a musician/band for its audience, which makes it doubly ironic that the touring show today remains one of the big ticket items) and of despair.

It is glum. A real downer. And musically monochromatic outside of some of the special effects and Gilmour's metallic sheen guitar. Waters certainly doesn't sound like a cheery dinnertable companion. He'd be banging on about sadistic school teachers he had three decades ago.

Jay Cocks in Time magazine in February 1980 nailed the album and concert: "Lysergic Sturm und Drang like this has a direct kind of kindergarten appeal, especially if it is orchestrated like a cross between a Broadway overture and a band concert on the starship Enterprise. It is likely The Wall is succeeding more for the sonic sauna of its melodies than the depth of its lyrics. It is a record being attended to rather than absorbed, listened to rather than heard."

In part simultaneously being recorded in Britain and at jazz pianist Jacques Loussier's studio in France -- because if they delivered on schedule for a year-end release they'd get more percentages on sales -- the album was also a farewell for keyboard player Rick Wright who didn't want to sacrifice his already planned summer break to get his parts down.

Wright had also wanted to have a producer credit (another producer?) and his already tense relationship with Waters broke down completely. He'd had enough, was paid out and became the salaried Floyd.

Tough times and even Mason (the lukewarm water between the Tufnel and St Hubbins of Gilmour and Waters) concedes, "I still find it hard to really cover some of the events of this period properly. Roger was probably still my closest friend and we were still able to enjoy each other's company. But our friendship was increasingly put under strain as Roger struggled to modify what had been an oestensibly democratic band into the reality of one with a single leader."

Metallica would have just got in a shrink, but these were wealthy and educated English gentlemen.

Lyrically this was Waters' self-indulgent Psych:101 nadir: "Mother do you think they'll drop the bomb, Mother do you think they'll like this song . . . Mother should I run for president, Mother should I trust the government . . ."

Alongside Lennon's self-lascerating Mother of a few years previous this was infantile and melodramatic.

Alongside Lennon's self-lascerating Mother of a few years previous this was infantile and melodramatic.

Spread over four sides, you can see why it needed an architectural stage show (and film, with Bob Geldof) and Gerald Scarfe's art to prop it up.

The heavy question is, "Has anyone not stoned to the eyeballs ever sat through this in a single sitting?". Don't Leave Me Now is unlistenable, and it isn't alone in that.

Unremittingly bleak and self-indulgent, it is supported -- over four sides remember -- by a couple of stand-alone hit songs, among them Another Brick in the Wall which Ezrin suggested a 100bpm disco beat for . . . and got them a UK Christmas number one.

Cliff must've been miffed.

But Pink Floyd was fraying at the seams. Their '83 album subsequently named The Final Cut began life as "Spare Bricks" but morphed into a Waters rumination on his father's death in the Second World War (shades of Tommy?) and some link with Margaret Thatcher and the Falklands war.

Waters leaped into action, Gilmour was -- as always it seems -- tardy and unresponsive, and the resulting album was a Waters solo write in all but name (he had every vocal bar one) and came in the worst ever Floyd cover. The Hipgnosis team/Storm Thorgerson had been passed over and Waters designed it himself.

Waters leaped into action, Gilmour was -- as always it seems -- tardy and unresponsive, and the resulting album was a Waters solo write in all but name (he had every vocal bar one) and came in the worst ever Floyd cover. The Hipgnosis team/Storm Thorgerson had been passed over and Waters designed it himself.

He also directed a short film based on the album.

So a solo album by any other name . . . and given how dreary most of his solo albums have been since, perhaps a warning to punters?

Gilmour later said "We should have called it The Final Straw".

It sold fewer than a tenth the number of Dark Side (which, admittedly is still an admirable three million). Rolling Stone gave it five stars and it certainly contained some of Waters' most poetic and moving lyrics (The Gunner's Dream, Southhampton Dock, Not Now John) which captured an Englishness more commonly found in the work of Ray Davies, Paul Weller and Damon Albarn.

But it was a hard album to warm to, let alone like.

Part history lesson, but mostly cathartic for Waters (but had no universality to reach to his generation let alone another younger) and a leaden bore almost scrupuously free of tunes, memorable songs and other such redeeming features. Rather important things on a record album one might have thought.

Quite why the other members of Floyd went along with it is surprising. Perhaps by this time they had severed attachment to whatever the Floyd brand meant, or were busy doing other important things like racing cars and producing (Mason).

Interestingly Mason says the album was done at Mayfair Studios in Primrose Hill, London "close to a restaurant we all liked".

The album is drearily melodramatic and an ignominious way to end a band . . . . because with Waters quitting shortly after and litigation over the name thereafter this is exactly what it was.

"After the Final Cut was finished there were no plans for the future," said Mason.

But of course . . .

FOR . . . PINK FLOYD, PART THREE (1987-94) . . . GO HERE

post a comment