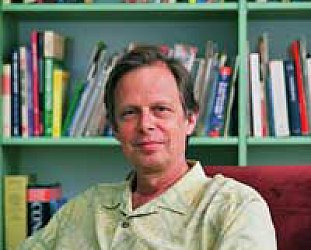

Graham Reid | | 12 min read

Steven Wilson: Index

Steven Wilson doesn't sound remotely

angry, just weary, when he says a major British newspaper declined to

review his new album Grace For Drowning. They said he was too

under-the-radar and no one knew who he was.

“Well, that's frustrating,” he

sighs, “because most of the music they write about is completely

unknown and unheard. Without wishing to blow my own trumpet I've had

two Grammy nominations, sold out the Royal Albert Hall and had a top

20 album. Yet they say nobody knows who I am.”

To be fair, he is hardly a household name. But he does have a 20-plus year career behind him, is the mainman behind the psychedelic prog-rock band Porcupine Tree which he formed in 1987 (10 albums since '91), has numerous production credits (notably Opeth), various side projects (Bass Communion as an outlet for his electro-drone solo work) and parallel careers (his collaborations with Tim Browness as No-Man, Blackfield with Israeli rocker Aviv Geffen). And he was recently remixing the early King Crimson catalogue with Robert Fripp.

He has appeared on the Pendulum album Immersion, and in 2008 released the first album under his own name (Insurgentes).

Now he presents another album under his own name, Grace For Drowning (reviewed here).

Now he presents another album under his own name, Grace For Drowning (reviewed here).

And of course because he was schooled in prog-rock of the late Sixties and Seventies, it is a double disc (cover on right) and comes out on double vinyl in a gatefold sleeve with a booklet.

Yet he concedes “I am totally aware I am making music that could never go into the mainstream. There is no way the mass market is going to find the time to listen to, absorb and engage with an album like Grace for Drowning.”

It arrives in the week of the Pink Floyd catalogue remastered reissues.

And by an ironic coincidence, Dark Side

of the Moon was one of your formative influences.

Yes, the reason Floyd is so in my DNA

is because my father was listening to Dark Side of the Moon when I

was very very young, and my mother was listening to disco and soul. I

used to hear these styles, and Dark Side invested in me the love of

the musical journey which took place across two sides of an album,

the idea that music could be more than just three minute pop songs.

The interesting thing about Pink Floyd,

and I don't mean this in any negative sense, is that it is quite easy

to emulate because the musicianship is quite simple. What is hard to

emulate is the scope and flow, but musically speaking it was quite

easy for me to pick up on what they were doing. Which I perhaps

couldn't when I listened to King Crimson when I was a kid. That was

more complex and impenetrable. So that was why I was drawn to it, I

could play the stuff and figure out what they were doing.

When I look at your age – you are 43

– you would have been 13 in that post-punk era. Were you ever drawn

to bands like Magazine or the Clash?

That's exactly what I grew up on. Bands

like Joy Division, the Cure, Cocteau Twins and Public Image were my

favourite bands, but at the same time my friends and I were

discovering things in our dad's and big brother's record collections, so I'm

a bit of a mixture. I grew up in the Eighties and still love that

music, but I also was finding something magical in the music from the

previous decade. But the dominant idea in my music is the idea of the

album as a musical continuum and a journey, and that's not something

you would learn from Eighties music. You had to go back to the

Seventies to get that, even the Sixties with St Peppers.

In your own work with Porcupine Tree

and other bands that has always been the project, that you would go

for the bigger idea?

In your own work with Porcupine Tree

and other bands that has always been the project, that you would go

for the bigger idea?

Yeah. When I started I saw a lot of

people doing other things but no one really doing that, so when I

started making music professionally in the early Nineties –

actually the first project I got off the ground was No-Man which I

suppose was closer to the music I grew up with in the Eighties with

dance beats -- but at the same time I still had my passion for

Seventies psychedelic progressive music. I started Porcupine Tree

because I wasn't aware of anyone doing anything similar at that time.

I suppose I thought I was doing it for myself and no one was

interested in that kind of music, but over the 20 years people have

gradually come around to it, to the extent that now it is almost

quite fashionable to be drawing influences from that era.

Porcupine Tree, almost by default,

became what I became known for because that audience outstripped the

other projects, and this solo project is more of a way to draw more

of the strands together . . . although having said that, this album

is more of a homage to that era.

The first time I heard Porcupine Tree

was many, many years ago and I remember thinking at the time it was

woefully unfashionable because it ran contrary to everything that was

going on.

Certainly for the first three or four

albums I was on an island. But the audience was slowly growing and

then everything changed in 1997 when Radiohead did OK Computer.

Suddenly people were using the p word, 'progressive', and it wasn't a

negative thing any more. Out of that grew a whole movement of

genuinely ambitious album-orientated music from people like Muse, the

Mars Volta, Flaming Lips . . . All these bands made it cool for the

album to be a conceptually ambitious piece. I can't claim to be ahead

of my time, but it took four or five albums before anyone in the

mainstream media took it seriously.

You are now embraced by that mainstream

music media?

To an extent. I don't think I will be

embraced in the way that the bands I have mentioned before are

because I committed the terrible crime of building an audience

without their help. If you do that they never really forgive you or

embrace you. So whereas bands like Radiohead and Muse were broken by

mainstream media, Porcupine Tree already had a sizable audience and

[the music media] didn't like that. But grudgingly now I do get some

coverage.

Any coverage now has to come to terms

with the vast history you have behind you.

I suppose there is an element of

laziness on their part to investigate that. Last week one of the big

newspapers here said they wouldn't review my album because I was too

under the radar and no one knows who I am. Well that's frustrating

because most of the music they write about is completely unknown and

unheard. Without wishing to blow my own trumpet, I've had two Grammy

nominations [best mix for surround sound for the PT albums Fear of a

Blank Planet and The Incident], sold out the Royal Albert Hall and

had a top 20 album. Yet they say nobody knows who I am. This is

partly their ignorance but also a willful laziness to not bother to

investigate or find out . . . and maybe the history is almost

daunting. That continues to be frustrating but it also makes for a

quintessential cult band in a way.

And you have other avenues, the website

for Grace for Drowning has all the information and I don't need

anyone to mediate for me. I can find out what you have done, look at

the video . . . You live in a different age now.

I'm not conscious of mainstream media

anyway I suppose, I don't watch television or read the music press.

Most of the culture I like are things you have to find and life has

taught me the things which inspire me the most are those things you

have to make the effort to find. The only real exception to that was

that golden era from the late Sixties to mid-to-late Seventies when

in some kind of twilight zone really creative and ambitious music

became the mainstream for a very short period of time. It was strange

anomaly because generally speaking the mainstream has been about

appealing to a mass market with the lowest common denominator and has

been about marketing as opposed to creativity, and profits rather

than art. And that is what drew me to that period, and the more time

goes on that period does seem to be an incredible anomaly in the

history of music.

Yet all those bands like Pink Floyd,

Yes, King Crimson, Led Zeppelin and the Who all sold by the

truckload. So people wanted it.

That time was very different. We didn't

have cellphones, the internet, Sony Playstation and a hundred

channels of television or home cinema. It was that period where

history conspired for it to be possible to make music which required

people to engage with it on a deeper level. And people did, in their

millions. No chance now, no chance at all that's going to happen now.

And on that cheerful note you are

releasing a double album, 90 minutes of music, into a world where it

has no chance at all?

(Laughs) Absolutely. And I am totally aware I am

making music that could never go into the mainstream. There is no way

the mass market is going to find the time to listen to, absorb and

engage with an album like Grace for Drowning. I know that. But music

is something which has to be in some way a selfish pursuit, a

self-indulgence.

I didn't become a musician to make money, to be a mainstream success or be a star. I made music because there was something magical and romantic about it. So I do it in a willful, self-indulgent way because I believe that is what all true artists do. If you want to be an entertainer then that is a different business. I'm not in this as an entertainer.

So I am accepting my fate in a way to be a cult artist, and I don't believe it is possible to make an album like Dark Side of the Moon now and reach a critical mass. I think the last time anyone did that was with OK Computer and that is 15 years ago. Since then the technology and the distraction have multiplied ten fold, so I don't believe an album like OK Computer could have any chance of reaching a massive audience today.

A band that is already huge has got much more of a chance than I have. If you have the ears of the world you can perhaps pull that off, but it is still going to be tough.

What I notice about Grace for Drowning, beyond the music, is the way you present it to people. There is this

value added package with artwork, it is on vinyl, there is a book and so on. You give

the audience something they don't get with just the download.

What I notice about Grace for Drowning, beyond the music, is the way you present it to people. There is this

value added package with artwork, it is on vinyl, there is a book and so on. You give

the audience something they don't get with just the download.

Yes, it certainly helps but I didn't do

that out of any altruistic motive, it was purely because the romance

of music is based in the Seventies and you look at the way people

were packaged this music in gatefold sleeves with lyrics, gimmick

sleeves . . . There was something about the presentation extended the

idea that the creativity behind the music didn't stop with the music

but extended to the packaging.

Unfortunately with CD, although the

sound is improved, the presentation is neither art nor software, it is

somewhere in between. What is interesting is seeing record companies'

livelihoods disappearing so they are almost forced in way to make

people want to invest in a physical product. Which is a good thing,

it is almost bringing it back to that great era.

I love that, but have always pursued

that approach because the creativity extends to all aspects of the

presentation.

You've gone out with this album under

your own name. Do you see a clear separation between Porcupine Tree

and what Steven Wilson does?

Obviously there is a cross-over but

there are many aspects of my solo career that I know Porcupine Tree

wouldn't play. The thing about being in a band, and it is one of the

good things although it might sound negative, is that it is limiting.

But that limiting factor gives music its personality and gives the

band its identity.

But the thing about a band is you have to find the common ground, and between four people is a relatively small area of music we want to play. So even though I wrote most of the music for Porcupine Tree I'm aware of what that common ground is, so I am writing in that area.

The solo career has none of those limitations or on the musical forces I can employ. On a solo project I can hire anyone I want so it is a more open musical palate which is a danger in that you could end up with a mess of an eclectic record banged together. That is why it took me almost 20 years into my career before I had the confidence to make a record under my own name which brought together all the various strands of my musical personality. I listen to industrial music or drone music or disco or ambient music, how do you pull that together? It's just a question of taking the time.

This covers a lot of musical territory

but it does seem coherent and cohesive which draws together many

strands. Belle de Jour is such a delightful piece.

This covers a lot of musical territory

but it does seem coherent and cohesive which draws together many

strands. Belle de Jour is such a delightful piece.

I'm proud of that, it's one of my

favourites. It is a homage to European film soundtracks and I was

thinking very much in the style of Ennio Morricone and Nino Rota and

those kinds of people and what they were doing in the Sixties and

Seventies.

What I loved about them was they often had an almost childlike lullaby quality but there was also something sinister going on underneath. The theme to Rosemary's Baby has that too, and I was trying to tap into that sensibility with that . . . and of course Belle de Jour was a french film of that era. I don't know who did the music for it though but its a movie I particularly like.

Index and Raider II, there is something

about the way the chords progress which says to me that here is a man

who knows his King Crimson intimately.

Yes I do. One of the launching pads for

this record was coming straight out of remixing their early albums

and my head being so full of that music. I love that music but you

can't go that deep into it without decoding a little bit about how

they made it and some of the techniques which I hadn't fully

appreciated before.

So my head was full of that music when I started to write Grace for Drowning, so if course that had a strong influence, the input always affects the output. Most people have picked up on the Crimson aspect and I'm not going to deny that, and I'm actually quite proud of that. They were one of the bands along with Floyd that formed my musical DNA.

Your hopes for Grace For Drowning then?

You've talked it down in terms of it being a massive seller. When you

tour will you do it in its entirety?

Your hopes for Grace For Drowning then?

You've talked it down in terms of it being a massive seller. When you

tour will you do it in its entirety?

Some of it is quite tough, Belle de

Jour for example, I can't imagine how we could do that, it's all

acoustic.

But about 75 percent of the record will be part of the tour and the rest will be tracks selected from my previous solo record Insurgentes.

You are starting in Europe and that

seems always a good market for you.

Yes, we are starting in Europe and then

America which I also good. But it is quite an expensive and elaborate

show to put on, there is a lot of multi-media and a six piece band so

it isn't cheap.

What about the UK, are they immune to

your charms?

In the UK sales have been good but the

media does ignore me, but I don't lose any sleep over that anymore.

I'm still here and most of the bands the music press were waxing

lyrical about have long since disappeared into the mists of time. (Laughs)

post a comment