Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The sound of Beatlemania

Some photographs are deafening. Consider the images of American kids screaming at the Beatles in late 1964. Even now, more than four decades later, those who remember the times or have seen the footage will hear an inexplicable noise as if it were alive and ear-shattering right now. Beatlemania from this historical distance -- a world of moshpits, gangsta rap killings and bellicose stadium rock -- seems almost quaint and naive, if pretty noisy.

Yes, girls and some boys screamed until they were hoarse -- but they stayed in their allocated seats.

And yes, there were incidents like someone trying to snip a lock of Ringo's hair at a British embassy reception in Washington, which illustrates how far up the social register the mania extended.

But it all seems as innocent as songs that said, "I wanna hold your hand."

What few recognised at the time was that 1964 marked a seismic shift in the world's collective consciousness. For Americans the Kennedy assassination of November 22, 1963 (coincidentally the day of the release of the With the Beatles album in Britain) was receding rapidly, and necessarily, into the past.

The Beatles' appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February '64 signalled the start of the change. A week later they went to Florida and sparred playfully with Cassius Clay, the new world heavyweight champion and soon to become an equally iconic figure of the era, Muhammad Ali.

Then they toured Australia and New Zealand, and in August returned to America for their first fully fledged stateside tour: 32 shows in 24 cities over 34 days. It started a week after their debut film A Hard Day's Night opened in 500 cinemas across the country. And the world started shifting on its axis.

American engagement in Vietnam began in earnest when the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August '64 -- passed 12 days before the Beatles' opening concert at San Francisco's Cow Palace -- authorised the use of US military forces. Bob Dylan had emerged as the living link between the Dust Bowl songs of Woody Guthrie and the emerging protest movements. The Free Speech Movement started at the University of California in Berkeley, and the Civil Rights Act was passed a fortnight after Ku Klux Klan members murdered activists in Mississippi.

In New York at the end of their tour, the Beatles met Dylan and had their first taste of marijuana.

This was the same year My Fair Lady swept the Oscars, a film which now seems so 1950s in this rapidly changing period for which the Beatles would provide the soundtrack.

At the centre of this new world were these four young men from Liverpool -- the oldest Ringo Starr only 24, the youngest George Harrison a mere 21 -- whose music invigorated a generation and whose style spread like an infection. Moptops became as common in Japan as on Merseyside.

There is little left to say about Beatlemania except perhaps through photographs, and photographers were everywhere. Except on the inside.

There was one, however, the Berlin-born New York-domiciled Curt Gunther, who had met and photographed the Beatles in London the previous year. He was invited to travel with the group, yet few of those photographs have been published. Until now.

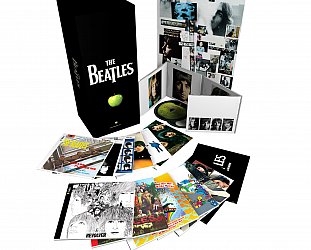

Mania Days -- a 140-page, large-format, leatherbound limited-edition book from Genesis Publications -- offers Gunther's insider view of the Beatles in late '64. There are playful shots of Ringo as a cowboy when on a rare day off they clowned around at a ranch in Texas, and serious images of a tight-lipped John Lennon scowling down a battalion of journalists at a press conference.

Among the 350 black-and-white images (some tinted) there is the mundane -- Harrison on a hotel floor playing Monopoly -- and what would become the terrifying, mobs of fans surrounding their car.

This time of their greatest triumph also meant the end of so much else. Because of the press of fans, they retreated into a cocoon. The group Lennon once referred to as a pretty good bar band would from then on be placed on distant platforms in the middle of baseball stadiums. In later life they repeatedly said that because they couldn't hear themselves over the screams, their playing got worse and they hated that. They were musicians after all.

Even as early as late '64 a weariness was creeping in. You can see it in the photos of Harrison slumped on a couch and in the tired eyes of Ringo caught backstage. A death threat was made against Ringo, the sender claiming he was Jewish. "The one major fault is I'm not Jewish."

"The only peace they got," said producer George Martin later, "was when they were alone in their hotel room watching television and hearing the screams outside. That was about it. A hell of a life really."

Said Harrison: "It was a very one-sided love affair. The people gave their money and they gave their screams, but the Beatles gave their nervous systems, which is a much more difficult thing to give."

For America and the world, Beatlemania signalled the end of one period and the beginning of another. For the Beatles themselves, however, who played their final public concert at San Francisco's Candlestick Park less than two years later, it actually marked the beginning of an end.

Either way, nothing would be the same after the mania days all those years ago.

post a comment