Graham Reid | | 5 min read

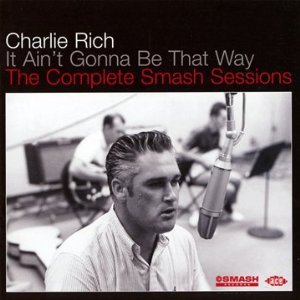

Charlie Rich: Dance of Love

When the Beatles visited Elvis Presley for the first and only time in August 1965, it wasn't quite the great meeting of minds or collision of musical genius as might have been expected.

The Beatles were, by their own account, so into marijuana at the time they forgot where it was they were going until the limo pulled up outside Elvis place in Los Angeles' Benedict Canyon.

When they got inside -- with Elvis' Memphis Mafia in attendance -- the Beatles were a bit overwhelmed and neither party had much to say. George Harrison slipped off to discreetly score some weed from the Mafia guys (they had none), Ringo remembers playing pool, McCartney later spoke of Priscilla descending the staircase wearing some kind of crown, and Lennon seems to have sniped a little at Elvis for not playing Sun-styled rock'n'roll anymore (according to Chris Hutchins and Peter Thompson's rather unreliable account in Elvis Meets The Beatles).

But one thing all parties agree on: that Presley was playing the same song over and over. It was Charlie Rich's big hit of the moment Mohair Sam.

A slinky slice of radio pop with a memorable piano part, subtle saxes and Rich's strong and soulful voice driving it, Mohair Sam was Rich's biggest hit for the Smash label, just another of many labels he passed through in his long but intermittent career.

Rich, out of Arkansas, had been one of the last acts on Sam Phillips' famous Sun Records in the late Fifties which had launched itself a few years earlier with artists like Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash and Roy Orbison.

But by the late Fifties when Rich arrived all of those big names -- except the then-disgraced Jerry Lee Lewis -- had left the label. And although Phillips was sure he had a another real talent in Rich, his interests were elsewhere. Rich's short-lived period at Sun -- during which he recorded 80 songs, among them Who Will the Next Fool Be which was later a hit for Bobby Bland -- was marked by poor promotion and none of his originals, nor those of his songwriter wife Margaret Ann Rich -- were successful.

Sun only released 10 singles and an album.

In '63 Rich signed with RCA in Nashville for their small label Groove but his producer there, Chet Atkins, couldn't see a way to get Rich out to the wider public. And no wonder.

Charlie Rich had a soulful voice (he often sounded like a black artist) but was also steeped in country and r'n'b, and he loved jazz. He'd scored a top 30 hit with Lonely Weekends in '60 but his own material and Margaret Ann's addressed all of his musical interests so there was no consistency (other than quality) in what he presented.

But then Rich got lucky.

When RCA dropped him after a year on their books with no conspicuous success, he washed up at Smash, a small subsidiary of Mercury Records where he was taken on by A&R man/producer Jerry Kennedy who had just finished nurturing the difficult comeback for Jerry Lee Lewis.

Kennedy was a great supporter of Rich -- Margaret Ann later said he was "a ray of sunshine in a den of iniquity" -- but it was always going to be a struggle. Not only was Rich a musical loose cannon in his passions (which Kennedy perversely but to his credit, encouraged), but he was prematurely grey and slightly portly, which was hardly endearing in the teen market which was dominating pop radio at the time.

He was also often trapped behind the piano with slick-backed hair at a time when mop tops with guitars were where it was all happening.

But what a talent he was. Among the 29 tracks he recorded for Smash up until he was dropped in late '66 are songs you could imagine Elvis singing if he'd had more caring management at the time. Rich pours his soul into deep ballads (Margaret Ann's A Field of Yellow Daisies which bridges Elvis with Bacharach is a standout) and reaches for the spirit of Motown on his original Dance of Love (imagine PJ Proby -- who covered Rich's Lonely Weekends -- sitting in at Hitsville USA).

Ace Records out of Britain -- the company behind the exceptional, recently released Fame Studio Story -- have pulled together It Ain't Gonna Be That Way: The Complete Smash Sessions (distributed by Border in New Zealand) and it is jewel box of precious gems.

Ace Records out of Britain -- the company behind the exceptional, recently released Fame Studio Story -- have pulled together It Ain't Gonna Be That Way: The Complete Smash Sessions (distributed by Border in New Zealand) and it is jewel box of precious gems.

Man About Town (a recently discovered recording, written by William Young and something of a thematic sequel to Mohair Sam) finds Rich ripping into it in the manner of Ray Charles, the string-enhanced So Long has the urgency of an early Springsteen or Willy DeVille heart-acher, and on William Cook's You Can Have Her sounds pure Presley on a blindfold test. And yes, the King covered it in '74.

He is a country artist (I Washed My Hands in Muddy Water, the B-side of Mohair Sam which Johnny Rivers heard, covered and sold a million) and an r'n'b singer playing honky tonk piano (Down and Out), and he could tear things up like Ray Charles (his rollick through Joe South's Let the Party Roll On).

He also sang songs which defined hurt and wronged (Everything I Do is Wrong) and headed for the swamp on Moonshine Minnie. There's a strange, baroque piano part in the peculiarly timeless No Home.

Okay, neither She's a Yum Yum and Hawg Jaw are the strongest lyrics by Dallas Frazier (who wrote Mohair Sam) and Double Dog Dare Me must have seem irredeemably dated in '66. But Rich turns in committed performances.

And surprisingly, aside from Mohair Sam, none of the best here (and that's about 20 tracks) damaged the charts at the time.

Yet just as Roy Orbison created a distinctive and defining body of work at the Monument label (captured on the set The Monument Singles Collection 1960-1964), so too you could argue that Rich defined himself at Smash with these songs.

He continued to record -- first for Hi and then Epic with Billy Sherrill where he had MOR hits with Behind Closed Doors and The Most Beautiful Girl in the World -- and in '74 he was voted Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association of America.

But he fell into drinking -- he famously pulled out his lighter and burned the paper when announcing John Denver had won the Entertainer category the following year -- and mostly retreated from the public gaze (aside from a few country hits for his new label Elektra, including a version of Eric Clapton's Wonderful Tonight) until '92 when he recorded Pictures and Paintings with writer Peter Guralnick as producer. It was to be his last album.

Charlie Rich -- in later life known as "the Silver Fox", admired by singers and songwriters, and Elvis -- died in 1995. He was 62. Margaret Ann died in 2010.

Charlie Rich -- in later life known as "the Silver Fox", admired by singers and songwriters, and Elvis -- died in 1995. He was 62. Margaret Ann died in 2010.

Rich's legacy from the Smash sessions is that of a fine interpreter with a deep, emotional but controlled voice in the manner of Presley, but someone who could turn his talents to string soaked ballads, roadhouse rock and tear-stained songs where the outsider looks at life.

Peter Guralnick called Charlie Rich "the soul of sincerity" and wrote that he and Margaret Ann had a "capacity for honesty".

They are two rare qualities -- and these are rare recordings which often embody them.

post a comment