Graham Reid | | 3 min read

In my experience, jazz people tend to live in the past. Radio programmes are more often about the greats of yesteryear than the living, jazz mags essay Ellington over ECM, and in any given year you get the clear message that record companies are more interested in reissues than recording new names.

Jazz musicians too contribute to this: older hands are frequently sniffy about newcomers who haven’t assimilated the history as they have, and many refuse to appreciate the changing times and contexts.

Of course jazz isn’t alone in this regard -- ask anyone who was there for the Sixties and they are bound to argue that the best rock music was made back then and Arcade Fire, if they have heard them, aren’t a patch on the Doors. Or some such spurious comparison.

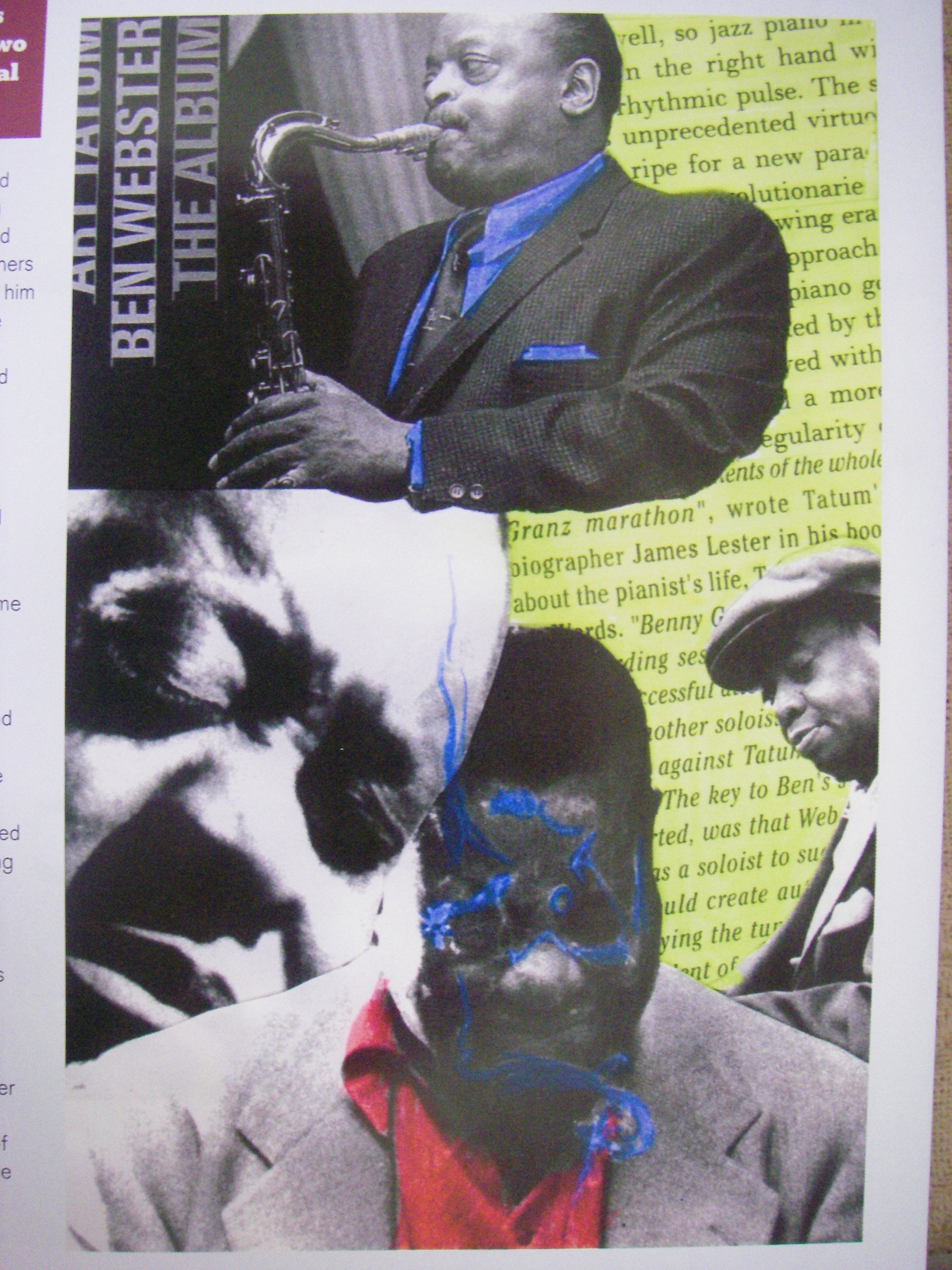

Mindful of how jazz can so often be mired in its illustrious past, it makes it awkward therefore to hail the reissue of an album recorded over 50 years ago. But when pianist Art Tatum and tenor player Ben Webster made their sole studio recording in September 1956 they not only captured magic and made a landmark album, but unbeknownst to them it would be the great Tatum’s last studio session. He died less than two months later.

Tatum and Webster had recorded before that session, but just four songs for radio in June 1944 in a large ensemble, and they are widely dismissed as minor pieces.

But in 1956, at the instigation of jazz entrepreneur and record company boss Norman Granz, Webster and Tatum -- with bassist Red Callender and drummer Bill Douglass -- went into a California studio and recorded seven tunes notable for their ease, effortless interplay and unpretentious invention.

Tatum at the time had long been a legend: his first sessions in New York over 20 years before announced him a genius. Back then he took tunes which were almost threadbare (Tiger Rag among them) and explored them in different ways to bring new life to them.

Born in 1910, he seemed to belong to a much older era but his stylish, sometimes throw-away, improvisations foreshadowed bebop of the late 40s and by the time he arrived at the session with Webster he had released a series of solo albums on Granz’s Pablo label entitled, with some justification, The Genius of Art Tatum. (They were reissued on seven CDs in the early 90s as The Art Tatum Solo Masterpieces).

Tatum was a self-taught prodigy who learned by ear from player-piano rolls his mother had. The story goes he learned to play duet pieces solo because he was unaware there were two pianists on the original recordings.

Much of his recording career were solo sessions because few musicians could keep up with his melodic inventiveness and speed.

He was not a man to be messed with (he made his name outplaying Fats Waller in a cutting contest) and knew his own worth. If he didn’t, others told him: Rachmaninoff considered him the best pianist in any style, Charlie Parker and George Gershwin were admirers and influenced by him, and apparently the late Oscar Petersen refused to touch a piano for two months after hearing Tatum.

Saxophonist Ben Webster was also an admirer, and as much loved as Tatum was admired. His style -- honed in Ellington’s orchestras in which he was a star player -- became more laidback over time but always sounded soulful, heartfelt and distinctive. As with trumpeter Chet Baker, Webster’s later relaxed sound is identifiable from the first bar.

I doubt you can listen to My One and Only Love from the reissue of the Tatum/Webster sessions (entitled simply The Album) without swooning as Webster’s woody tone weeps in and holds fast to the slow melody before dragging it into the clouds.

And that kind of magic pervades these seven tracks where Tatum never tries to outplay Webster, as he had done to others. The mutual respect is evident as melodies rather than personalities are paramount.

Webster later said his version of Night and Day here was among the best recordings he ever made -- but among the other ballads are some its equal.

This was two jazz giants laying back into material they knew intimately (All the Things You Are, Where or When, Gone with the Wind among them) and it stands as a landmark recording.

For this new reissue the producers have tacked on five Tatum solo tracks from two years previous, versions of the songs from the session with Webster in which you can hear how much flourish Tatum could bring to such ballads.

They serve as object lessons in piano playing -- even today jazz pianists study Tatum transcriptions -- but more than that they illuminate just how much he held back in order to make these tunes with Webster sing -- and be sublimely and simply soulful.

This is one jazz album from the vaults which deserves whatever attention it can get, even in the fast-paced and uncertain 21st century.

Perhaps more so because of that.

This article first appeared in Real Groove magazine, February 2008

post a comment