Graham Reid | | 6 min read

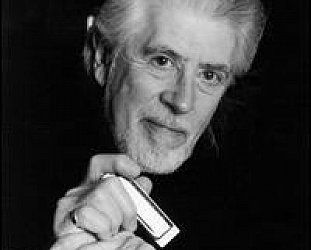

Oddly enough, this is not the best time to talk to 64-year-old bluesman Buddy Guy - despite him having released Sweet Tea, one of the finest albums in his long career.

It is days after the death of his contemporary John Lee Hooker and Guy is understandably philosophical rather than keen to talk up his new album which was, uncharacteristically for this seminal figure in Chicago blues, recorded in rural Mississippi.

Guy is thinking about John Lee and the lineage passing on.

"You know, this past month I been doing a lot of interviews for this album and I been pointing out there's only the three of us left from that time, me and him and BB King. We was all around at the same early time. Then I gets this call just before I go on stage. Now it's just me and BB from that era of the 50s."

It's true -- singer-guitarist Buddy Guy is one of the final few of his seminal generation.

Born in Louisiana in July 1936, he played with Slim Harpo and Lightnin' Slim before moving to Chicago at 21 where he played clubs before running into the legendary Willie Dixon, who played on the first Chuck Berry sessions, and wrote classic blues tunes such as Hoochie Coochie Man and Back Door Man. Dixon scouted for Chess Records.

Guy recorded for Chess between 60 and 67, although the label didn't know what to do with this towering talent and sidelined him into pop-styled soul tunes aimed at the charts.

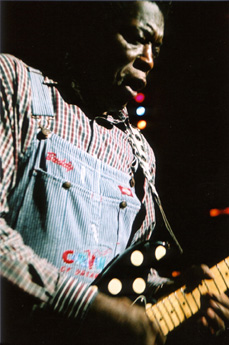

All the while, however, he was hauling an audience into clubs with a guitar style which owed debts to southern players such as BB King and the tough Texas tradition of T-Bone Walker.

Guy and his contemporaries Otis Rush and Magic Sam brought the solo guitar to the fore and his influence on other musicians was always considerably greater than his record sales.

"Even my children didn't know who I was until they turned 21 and could come into a club. They don't see me on the music television or hear me on the stations they listen to. Radio done quit playing blues music, especially if you are black, so we have to take it to people.

"Some stations do a little, but not like they used to in Muddy Waters' young days. Then you'd put a record out and hear it mixed with all the rest on radio. If you are a superstar now though, no matter what you do, that'll get played. We don't get that freedom."

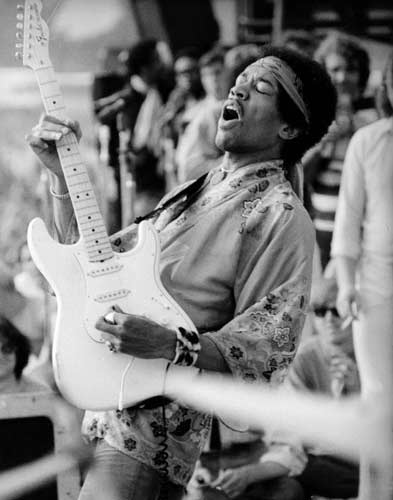

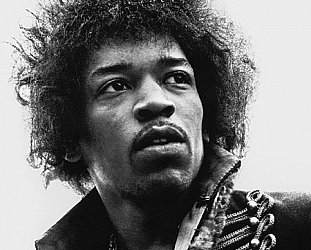

Interestingly for this man, whose flamboyant style was a clear influence on Jimi Hendrix, a definitive 60s book on the blues by Paul Oliver notes: "Guy's antics, his deliberate and entertaining showmanship, while adding nothing to his music, have made him extremely popular ... "

For many years Guy was paired with harmonica-player Junior Wells and, as is typical in the blues, they had a tetchy relationship.

They recorded classic Chicago blues such as Messin' with the Kid, It Hurts Me Too and Vietcong Blues, all of which appeared on the influential Vanguard Records' mid-60s compilation Chicago/The Blues/Today!.

Guy's white-knuckle style was cited by Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, then after the 60s, as with the blues, his star declined, despite touring constantly. When he came to record Damn Right I've Got the Blues in 91 with guests Beck, Clapton and Dire Straits' Mark Knopfler he had been without a recording contract for 15 years.

"I'd been denied the right to make records and finally went to England and did Damn Right and thought about Jimi Hendrix and how he did that too. Maybe that's where I should've been all along."

Damn Right brought Guy back to the foreground and in the past decade he has been acknowledged as the distinctive, brittle, rock-blues guitarist he most righteously is. His unnaturally youthful demeanour belies that he's from that generation of whom there are so few left -- "John Lee, BB and me."

Then there were two. But that's not entirely correct as Guy's new Sweet Tea album attests. In the past five years a new, yet also old, sound of the blues has emerged on the Fat Possum label. Artists such as seventy-something RL Burnside, Junior Kimbrough and T-Model Ford have recorded edgy, primitive blues that have been looped and sampled to reinvigorate the idiom. Their albums are played on student radio stations. A year ago Guy was invited to Fat Possum's Sweet Tea studios (hence the album title) in rural Mississippi where he recorded songs by Kimbrough and T-Model Ford with various Fat Possum musicians. The results are extraordinary: the album opens with Guy in rare acoustic mode saying he's an old man and can't do it no more, then he bursts into his archetypal growling and moaning guitar over earthy grooves and loops.

A year ago Guy was invited to Fat Possum's Sweet Tea studios (hence the album title) in rural Mississippi where he recorded songs by Kimbrough and T-Model Ford with various Fat Possum musicians. The results are extraordinary: the album opens with Guy in rare acoustic mode saying he's an old man and can't do it no more, then he bursts into his archetypal growling and moaning guitar over earthy grooves and loops.

It's a marriage of the old and the new. You can hear the man who influenced the Hendrix generation but also hear flickers of the untutored rural blues he heard as a child.

"Yeah, it's the natural stuff we started playing. When they invited me to Mississippi I thought I'd met the greatest of the musicians who'd come out of there. But it just goes to show you never know it all.

"When they found Junior and all those other guys I thought, 'Man, this is the original thing and I'm going back to that stuff.'

"But they said they wanted me to play Buddy Guy along with all they did and then pulled out all those amplifiers with cobwebs and plugged me.

"At first I didn't think I was going to like it. But there's a cut I played for 12 minutes [I Gotta Try You Girl] because they just couldn't stop me from playing."

When he got the call Guy wasn't aware of Fat Possum but after being denied recording opportunities there was no way he would say no. He was surprised, and delighted, when he saw the old studio in the woods.

"It's like the original studios were. You drive up and say, 'Is this a recording studio?' It just looks like another house. Actually I didn't record nothing in the studio, they put me in the hallway and put the band in the studio, they didn't want me to get influenced by them.

"I felt I had to sit down and practice that music because it's not by the book, you just have to feel it. On I Gotta Try You Girl there's no changes, we just played it the way the late John Lee played, just get a groove. I'd lost all that because I'd learned all the changes and the six-, eight- and 12-bar blues, so I had to go back.

"It's like an automobile. You get in a car now and press on the gas and the car does the rest where in the olden time you had to do all the gear shifts. This takes you back to something like that. It's an earthy and raw style of the blues I grew up with."

It's also exceptional and rare music and, as the man notes, there aren't a lot left who can feel it any more.

Buddy Guy, who deserves the last word, is one of the final few still out there doing it: "The music I love is like an endangered species, and we protect an endangered species."

post a comment