Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Alexander "Skip" Spence: Little Hands

Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd and Roky Erickson of Thirteenth Floor Elevators don't own the category of "mad Sixties acid casualty" exclusively.

Alexander Spence -- aka Skip Spence -- deserves to be entered among the "tuned in, turned on and dropped so far out he couldn't come back".

In the years before he died in '99 at age 52, he had become an itinerant, mostly homeless person in and around Santa Cruz and San Jose and sometimes in care.

But it has all started so well.

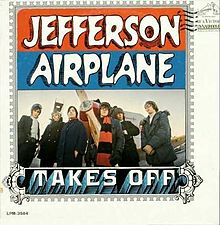

By all accounts Canadian-born Skip Spence was a charismatic figure in San Francisco in the early Sixties and that was what attracted Marty Balin to him. Balin offered Spence -- a songwriter/guitarist who had been in the earliest incarnation of Quicksilver Messenger Service -- a position in his newly forming band Jefferson Airplane. The position was as a drummer, but Spence took it, and was on their debut album Jefferson Airplane Takes Off in '66.

No matter. Spence simply joined up with another bunch of musicians to co-found Moby Grape where he was part of their distinctive three-guitar line-up.

The Moby Grape story of great promise, then rapid rise and fall is well known (and told here) but Spence wrote the classic psychedelic rock single Omaha on their debut album (as well as Indifference, and shared credits on Someday).

For their second album Wow, he contributed (among others) the two extremes on the album; the rocking Motorcycle Irene and the quirky, old time dancehall track Just Like Gene Autry. Spence seemed to fly from one end of the spectrum to the other . . . and in his personal behaviour also.

Through a combination of acid, increasingly erratic behaviour, a girlfriend into black magic and finally menacing band members with an axe, he was not just out of the group but into Bellevue Hospital in New York.

He was diagnsoed as a paranoid schizophrenic and held for six months.

But just as Roky Erickson did during his time at Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Texas, Spence wrote lyrics.

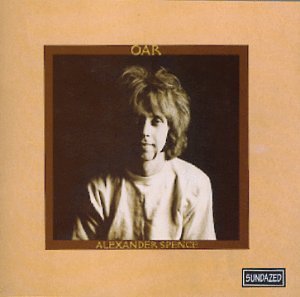

When he got out of hospital he used an advance from Columbia Records to buy a motorbike then headed down to Nashville where, over four separate sessions in December '68 (playing all the instruments) he recorded 22 songs, 12 of which made it onto his sole solo album, the self-produced cracked masterpiece that is Oar.

After the sessions he lit out for California and -- aside from a few scattershot moments with music -- thereafter became lost to us for decades. So it's likely Oar was unfinished . . . but there is something desperate, deep and deliberate about the songs.

They don't always sound like a man on the edge of sanity, in fact there is flawed beauty about many of the songs such as the gentle but vaguely menacing acoustic country ballad Weighted Down ("by the possessions, by the river for you to come") and he certainly hadn't lost any of his fluidity on guitar.

They don't always sound like a man on the edge of sanity, in fact there is flawed beauty about many of the songs such as the gentle but vaguely menacing acoustic country ballad Weighted Down ("by the possessions, by the river for you to come") and he certainly hadn't lost any of his fluidity on guitar.

It isn't without its dark spots however and the nine and half minute, droning and seductively low Grey/Afro certainly send chills down the spine, but again it is weirdly beautiful in the same way a Francis Bacon painting can be. It is a genuinely experimental piece which was more odd at the time than it sounds today.

Greil Marcus writing in Rolling Stone at the time referred to the strange folk quality of the Oar and the "sad, clumsy tunes that seem to laugh at themselves" but also noted, in the jargon of the time, "this is real music, not someone's half-baked idea of where it's at".

The opener Little Hands has a guitar part which sounds like it drifted out of the desert blues bands of the past decade.

The short but disturbing Books of Moses with its off-beat percussion, strummed acoustic guitar, crashing thunder and rain, and his desperate vocals is a man revealing the visions in his head, but also controlling them for outward consumption.

He also keeps the emotional anarchy under control in the disturbingly beautiful War in Peace which ebbs and flows over a stuttering and chiming electric guitar part which briefly takes psychedelic flight.

Spence doesn't keep any sense of time in the expected sense so the songs have a mercurial quality, and the way he overdubbed parts can sometimes sound like some other song has arrived in his head. But again, there is more coherence than a first listening might suggest.

The expanded edition of the album released in '99 came with the other pieces/songs from the sessions which provide even greater context.

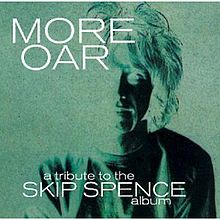

Just before his death a tribute album to Spence appeared and among those lining up were Robert Plant, Jay Farrar, Mark Lanegan, Tom Waits, Robyn Hitchcock, Beck, New Zealand's Alistair Galbraith, Mudhoney . . .

Just before his death a tribute album to Spence appeared and among those lining up were Robert Plant, Jay Farrar, Mark Lanegan, Tom Waits, Robyn Hitchcock, Beck, New Zealand's Alistair Galbraith, Mudhoney . . .

Illustrious admirers indeed.

Skip Spence may seem little more than a damaged casualty of his era and a footnote in rock, but Oar -- more so than Syd Barrett's similarly conceived post-Floyd solo sessions -- shows a man creating music that was emotionally challenging to himself and others, undeniably innovative and coming from some deep space within.

It is an album which rewards finding, and Spence a man whose career is worth discovering.

Skip Spence was also in three of the best psychedelic bands of his time -- Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape.

Who else could claim that? As well as an album as unique as Oar.

For other articles in the series of strange characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

The Riverboat Captain - Mar 5, 2012

Great stuff. And you picked my favourite track, too.

SaveClive - Mar 5, 2012

Thanks for the heads up here Graham,I will chase it down.Every half decent music collection should have some Jeff Airplane and Moby Grape.

Savepost a comment