Graham Reid | | 4 min read

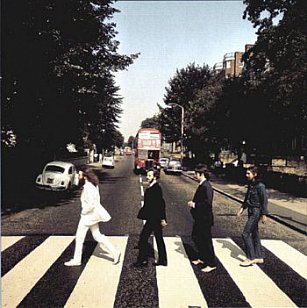

Long before you reach the most famous recording studio in the world you can hear the sound. But it is not music coming from inside the walls. It is the squeal of tyres as another car or truck slams on its brakes because a tourist - and often a whole group - has stepped on to the nearby pedestrian crossing to have a photo taken in imitation of an iconic image shot here on a late summer's day in 1969.

The suburban street is Abbey Road in London, now long passed into legend because of the Beatles' album of the same name.

Originally the group toyed with calling the album Everest after the brand of cigarettes a studio engineer smoked and they briefly thought of traipsing off to the Himalayas for the cover shot. But as time went on they wearied of even thinking about such things until on August 8, 1969 the photographer Iain Macmillan was summoned by Paul McCartney.

For 10 minutes, the Beatles walked back and forth over the pedestrian crossing while Macmillan, on a step-ladder in the middle of the road as a policeman halted traffic, snapped off half a dozen photos. Then the Beatles went off -- John Lennon and McCartney back to Paul's place, George Harrison to the zoo with roadie Mal Evans and Ringo Starr went shopping -- before they met at the studio later to continue work on what would be their final sessions together as a group.

When they delivered the finished album three weeks later they simply called it Abbey Road after the EMI studio where they had recorded all their music since that first audition with producer George Martin back in June 1962. It was a nice thank you-cum-homage and, ever since, hundreds of thousands of people -- Margaret Thatcher among them -- have been photographed in a similar pose on the crossing.

Nearby, a tour bus waited, ready to disgorge its cargo of temporary pedestrians.

My guide was an engineer/producer Alex Marcou who took me through the two main studios then for a cup of tea in the cafeteria.

The EMI Studios building at Abbey Road may be synonymous with the Beatles, but its story began long before the 60s. The nine-bedroom house - with five reception rooms, two servants' rooms, a wine cellar and a huge garden - was built in the 1830s and passed through many hands before it was sold to the Gramophone Company in 1929. It opened as EMI Studios in November 1931 with Sir Edward Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra through Land of Hope and Glory while George Bernard Shaw sat in the audience.

In the years before the Beatles arrived, a rollcall of genius climbed the steps to the modest doorway: Yehudi Menuhin, Sir Thomas Beecham, Sir Adrian Boult, violinist Jascha HeIfetz and cellist Pablo Casals. Fats Waller and Gracie Field recorded here, as did Paul Robeson, Al Bowlly and Vera Lynn.

A few weeks later their plane disappeared on a trip to France. Music from their final sessions wasn't released until 50 years later when copyright lapsed.

Then there were the Goons, and Peter Sellers with Sophia Loren recording their novelty hit Goodness Gracious Me and, in the pop era, Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Adam Faith, Frank Ifield and many more.

When the Beatles arrived, the studio was run on strict union lines and engineers wore white coats. In the late Thirties Winston Churchill visited and said he thought he'd come to the wrong place: "It looks like a hospital".

It would be three decades and the Beatles' odd work schedule before the place loosened up.

On my amble around - through where the Hollies, Pink Floyd and Ella Fitzgerald had also walked - Alex gave a running commentary and said if I wanted to come back I could stay in one of the two penthouse apartments which had been added. He mistook me for someone much more wealthy.

He sympathised. It was a studio after all and really only made sense when musicians were working there.

And then Alex - from the most famous studio in the world - asked what his prospects would be like in New Zealand: he was sick of the London traffic.

I broke it to him gently.

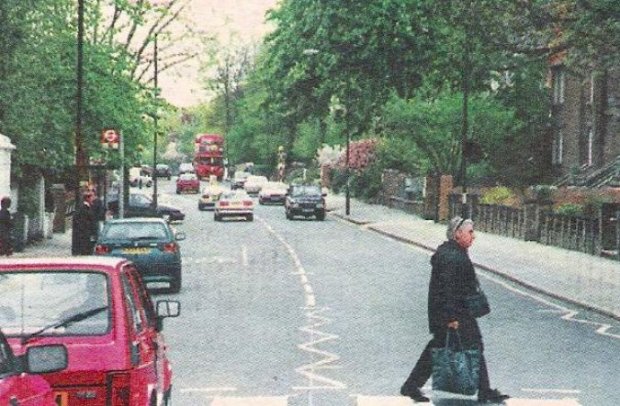

Later, I went back on to the pedestrian crossing where the most famous people of our time once strode.

I had to take a photo, it was an irresistible moment.

An old woman bent by shopping bags was trudging wearily across.

Not a fan in sight.

post a comment