Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Yoko is a concept by which we measure our pain

-- New York graffiti, 1970.

A voice that comes once in a lifetime; unfortunately it came in ours

-- Critic Jim Mullen, 1992

Yoko Ono was always an easy target. Conceptual artists who mount exhibitions of chess sets where all the pieces are white, or write books which consist of ambiguously and unintentionally hilarious instructions like “send smell signals by wind” are just asking for it.

You don’t have to be especially cynical . . . just have a quick quip at the ready.

Yoko Ono even had the surname for it.

And when she moved into the world of rock, at the shoulder of her partner John Lennon, she committed that grave heresy of believing it was an idiom for her own brand of conceptual art.

She screamed, she made records with two minutes’ silence on them and a radio being flicked past the stations. She breathed a lot . . .. then recorded it.

Oh no!

But all that was so long ago . . . around the time of the first Bay City Rollers hit and The Yes Album. (She doesn’t seem so bad in that context.)

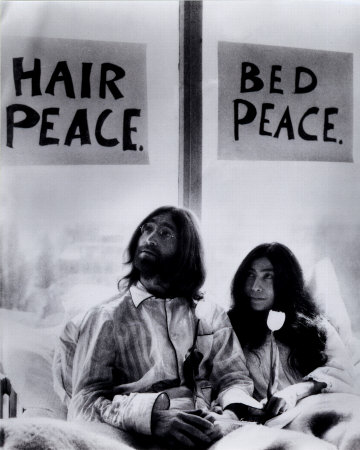

However there was a slow but incremental re-evaluation of Ono’s work after Lennon's death in '80 -- mostly orchestrated by Ono herself it must be said -- but one which cast her work in a more objective light than when editorial writers railed against the woman who was breaking up That Band and staying in bed a week for peace.

Her ‘89 exhibition of old works recast in bronze at New York’s prestigious Whitney Museum seemed, according to Jude Schwedenwein writing in the international art magazine Contemporanea, “to blur time in a peculiar way -- the old works appear fresh and immediate . . . Ono continually succeeds in provoking her audience to approach objects, images and ideas with a new perspective.”

That was also true of her six-CD box set Onobox which came as an objet d’art itself. Just over 100 songs thematically sequenced, beautifully packaged and scrupulously annotated and essayed. Old works presented in a new, commanding way.

Schwedenwein also noted Ono’s exhibition encouraged sympathy for the artist’s nostalgic reading of her period.

And that’s also true of material on Onobox, where her peculiarly naïve political and feminist idealism has an unworldly charm. But lyrics came second in her musical career and it was her debut album in ‘69, Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band, which was without precedent. At times Ono sounded like a torture session in an elevator shaft or someone gargling with razor blades.

It was pure, primal and almost animalistic. It was, in its own way, brilliant.

But most people hated it, although mostly they hated here: the earnest Ono (black hair, black clothes, unsmiling) became the focus of ridicule and contempt.

Yet the raw power of her vocals -- underpinned by searing Lennon guitar and Ringo Starr playing fierce drums as he rarely had or would again -- was awe inspiring. It took at least a decade before rock, in the form of punks like Siouxsie Banshee or arty types like Pere Ubu, caught up.

Kate Pierson of the B52s cited Ono as a major influence, Bowie called her work “dangerous, a subversive notion” and artists as diverse as Ann Magnuson from Bongwater, jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman and Cyndi Lauper pay tribute to Ono.

Because she was a conceptual artist and part of the Fluxus group (alongside John Cage and David Tudor) she stumbled into rock culture without preconceived notions.

She genuinely thought you could just sit in with the Beatles. Why not? You did group exhibitions with others.

Her lack of “rock training” meant she simply did her thing. Singles like the screaming imperatives of Open Your Box (the flip-side of Lennon’s weak and sloganeering Power to the People).

She had orgasms on record (a decade before Donna Summer) and thought nothing of releasing talk-pieces. She led Lennon through the abstract cut-up of Revolution 9 and posed naked with him -- full frontal and from behind -- on a courageously unflattering album cover.

It was its own kind of intellectual terrorism in a saccharine world of Mary Hopkins’ Those Were the Days, the chosen musical protégé of another Beatle.

Yet Ono could also sing something as childlike and simple as Who Has Seen the Wind, a piece of sweet innocence that wouldn’t sound out of place on Romper Room.

Ono was, if nothing else, “unique” as Eric Clapton wryly noted.

By her Approximately Infinite Universe double album of ‘73 however she started writing meaningful lyrics. Not the smartest of ideas because her dippy feminism in hot pants (not entirely approved of by more precise feminist thinkers at the time) was as jarring as her inability to scan a line.

She didn’t have the keenest sense of melody either. Couldn’t sing in fact . . . But accompanied by some of the biggest names in rock, she persisted and over the years hit the target with increasing frequency.

Most people didn’t hear her mid-Seventies albums so it came as one of those uncomfortable ironies that on the final Lennon-Ono album Double Fantasy of ‘80 that her songs were the stronger and more interesting than Lennon’s retro-Beatles pop (Watching the Wheels, Woman) and Fifties pastiche (Starting Over).

Ono’s single Walking on Thin Ice, the tape of which Lennon was carrying when he was gunned down, is astonishing in its blend of eerie lyrics, relentless dance beat and uncompromising attack.

Produce Nile Rogers (Chic) said when it came out that he played it non-stop and still considers it a great piece of work. Elvis Costello covered it on the Ono tribute album Every Man Has a Woman in the late Eighties.

The massive Onobox collected almost everything she recorded until ‘92 plus an album’s worth of unreleased material. And it confirms the diversity of her work.

There is the unearthly tonal style of Mind Holes and O Wind, the previously unreleased and quite remarkable The Path from ‘71 (a heavy-breathing piece of sonic impressionism) and the industrial haiku of Don’t Count the Waves. On Yellow Girl she comes off as some Oriental Dietrich and Midsummer New York sounds like a seriously disturbed Elvis.

Most of her work is barely disguised autobiography (It Happened) or her view of the rock world (Potbelly Rocker).

As a woman interloper into the boys club of rock’n’roll (and a “foreigner” at that) she saw the world very differently. Her curiously feminist work like Woman Power from ‘73 (with a massive, unrelenting band in support) sounds more focused now when separated from the often divisive intellectual debates of the time.

Sure, juvenile nonsense is (rather heroically) included in the Onobox: there is Toilet Piece (yep, the thing flushes for 12 seconds) and Telephone Piece (yep, you can guess). Her voice grates sometimes and her careless disregard for a melody can be irritating.

But removed from the contemporary comparisons with her partner (who only managed a four-CD box set) there is plenty to appreciate in songs such as Kiss Kiss Kiss or the dope-at-large period piece of Peter the Dealer and Death of Samantha. (Yes, this is the song that gave the Cleveland alt.rock band its name).

There are however, even in a set of 105 tracks some unfortunate omissions: AOS, the seven-minute piece she recorded with Ornette Coleman isn’t here, nor is the brutal live version of Don’t Worry Kyoko. It has been passed over in favour of the more restrained studio version. The nursery school Listen the Snow is Falling isn’t here either. Pity.

Obviously even this much Ono is too much for most to take, but the marketing machine can accommodate the casual shopper with the 19-track single disc Walking on Thin Ice which side-steps that gut-grabbing Plastic Ono Band debut album and experimental tracks in favour of a song collection.

It is a good one . . . .

But the real Ono is in the big picture. An artist before and after John Lennon.

Back in ‘73 Yoko Ono warned on Yes, I’m a Witch, only now released in the Onobox, that, “Yes, I’m a witch. Yes I’m a bitch. I don’t care what you say, I don’t fit in with your ways . . . You might as well face the truth . . . I’m gonna stick around for quite a while.”

And true to her word . . .

There are interviews, reviews and other overviews of Yoko Ono's work at Elsewhere starting here.

For other articles in the series of strange characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

Graham Dunster - Apr 24, 2013

Yoko is one of those frustrating - and thus rewarding - people. I recall picking up copies of her books for a few pence in London in the 70s, also being captivated by some singles then - and hating others. The Live Peace In Toronto 1969 lp is kinda cool. The world would be a less interesting place without her.

Savepost a comment