Graham Reid | | 7 min read

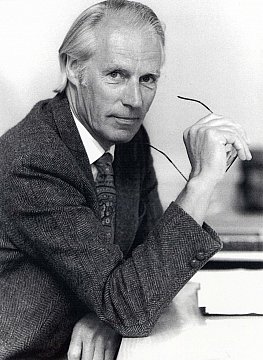

Of all the knights of pop -- Sir Cliff, Sir Paul, Sir Elton -- it is Sir George Martin, famously known as the Beatles’ producer, who seems the most deserving of the accolade.

It was November '95 when I met him in London at the launch of the Beatles’ Anthology albums. He was self-effacing, courteous and well-spoken. (At age 16 he'd heard his voice on tape and thereafter purged his North London accent and replaced it with a beautifully modulated non-dialectic Englishness).

He was, in an avuncular way, quite charismatic.

The gracious demeanour almost required the deference of addressing this distinguished, grey-maned gentleman as “sir”. And that was a year before he was knighted.

Martin’s most characteristic feature, however, has always been his modesty. He frequently says he feels a fraud for his long -- and, in rock music, unique -- association with the Beatles because, “I’m not a rock’n’roll person.”

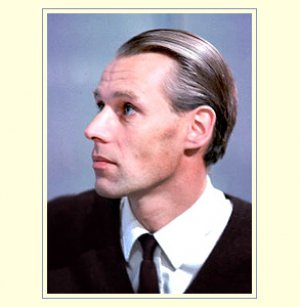

Indeed, he wasn’t. After military service in the Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War he joined the BBC, played occasional oboe and in 1950, on the recommendation of a professor at the Guildhall School of Music, was appointed assistant head of EMI’s Parlophone label. He learned to produce orchestras, recorded comedy albums with the likes of Peter Ustinov and, in 1955, at the age of 29, was appointed head of that almost moribund label.

When the Beatles arrived at Parlophone in June 1962, Martin was divorced from his first wife Sheena. By his own admission, because he had lost his own youth to the services and marriage he saw, through them, a way to have fun, albeit in pop music and at age 36.

That he and the Beatles -- whom he still calls “the boys“ -- changed the face of popular music and culture rests lightly with him. However, at the launch of the Anthology series, it was suggested that the tight security was more befitting a Middle East peace initiative and he was asked if people weren’t taking this all a bit too seriously. He sternly reminded the questioner of the immense pleasure the Beatles gave the world and yes, he did take that very seriously indeed.

The assembled journalists were silenced by his professional chastisement.

But then, as now, he is most often circumspect about the band that made his name. He diplomatically skirts around Sir Paul McCartney’s recent attempts at classical work, saying he and his wife, Judy, attended the premier of McCartney’s’ Standing Stone and “it was an extraordinary evening.”

It was very good, he says, and obviously one could be critical of it. “But I think it was a triumph for him because it was such an extraordinarily difficult thing to do -- and it took a long time and the collaboration with four or five other people … and it’s interesting because this is the same guy I had to persuade to use a string quartet on Yesterday. And now he is fully embraced in a symphonic medium.”

And those controversial Free as a Bird and Real Love singles which reunited the remaining Beatles with the dead Lennon? They were the only two Beatles songs he didn’t produce -- Jeff Lynne did the job. Was that because he didn’t think they were up to much or did he simply recoil from the idea?

“Both. The song Free as a Bird was very good and there’s another which hasn’t been done which is just as good, but the idea didn’t appeal to me,” he says ambiguously, while noting the poor quality of the recording Lynne had to work with.

Such circumspection has always made Martin a charming, if opaque, interviewee.

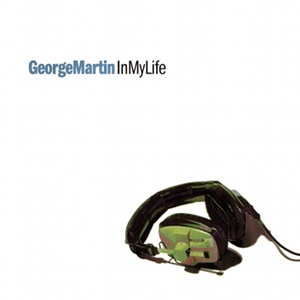

But now -- after 48 years in recording studios -- he is officially retiring.

His legacy secure, he departs with an album of Beatles’ songs by a dizzying -- and disappointing -- array of artists which includes yappy actor Jim Carrey hamming his way through I am the Walrus, Goldie Hawn giggling and yawning through a slow jazz swing version of A Hard Day’s Night and violinist Vanessa Mae fiddling about with Because.

Entitled In My Life after one of John Lennon’s more reflective songs -- here narrated by Sean Connery -- it’s a disappointing coda to an illustrious career. But, it must be said, it is another in his less-than-successful Beatle-appended projects such as the 1974 From the Beatles to Bond to Bach album.

However the thought of 72-year-old Martin is not being in his natural home behind a mixing desk is strange.

However the thought of 72-year-old Martin is not being in his natural home behind a mixing desk is strange.

“Well, it’s not exactly retirement,” he says in Brisbane, where he has been conducting orchestras in a programme of Beatles standards. “The thing is, I’m not making any more records and having worked in a studio for nearly 50 years, it’s a long time.

“I’ve worked with so many wonderful people and been very lucky and thought I’d make my last record and not let fate decide it. It’s not that I’m bored with it all, because I’m not, but I’m not as good as I was.

“As you get older you can’t run up the stairs as quickly, I play Cinderella tennis rather than the other stuff -- that's where you don’t quite make it to the ball -- and of course my hearing isn’t as good as it used to be.”

He admits he first identified hearing problems 20 years ago and, blaming too much loud music, warns young people of the dangers of full-volume rock. He notes, “Quite a few rock stars have this problem, and they obviously don’t want it to be generally known. Noise damages your ears, no doubt of it.”

Yet “retirement” seems such a Martin thing to do; considered, calm and rational -- and his pragmatism extends to being aware of his own mortality. “However, it’s nothing to worry about.”

He is equally humble about his place in history, dismissing it as “pretty small beer, really. Honestly.”

“I’m pretty ashamed there’s been so much hype. It’s not a question of being modest and I’m grateful to people who say nice things to me. But I know in my own heart where my real place is, and it’s nothing to be over-inflated about.

“I was very lucky to be part of that scene and it’s just the way it works out. It was just the right place at the right time and I’m very happy about that. But delusions of grandeur are out of it."

Despite having a “nice round number to finish on” -- his 30th number one single -- Elton John’s tribute to Diana Princess of Wales - sadly, In My Life deflates any laudatory career appraisal. Despite Celine Dion offering a fine version of Here There and Everywhere (“I wanted her to play a low-key affair and not to be over-dramatic”) and guitarist Jeff Beck blazing a path through A Day in the Life, there is little to recommend it.

And Goldie Hawn?

“I’m a tremendous fan and this album was me asking my friends and heroes to take part. She’s always been one of my heroes and she was everything in real life you would expect, a sweet person, great fun to be with, got a delicious giggle -- and she sings well, don’t you think?”

It seems diplomatic to side-step here and state a preference for Peter Sellers’ declamatory, mock-Shakespearean version of the early 60s. It is also a compliment: he produced that one, too.

It seems diplomatic to side-step here and state a preference for Peter Sellers’ declamatory, mock-Shakespearean version of the early 60s. It is also a compliment: he produced that one, too.

It must be said that after his Beatle years, Martin’s career was not quite as successful as might have been expected.

Albums such as Under the Milk Wood with Anthony Hopkins were over-produced; he rates his work with the jazz-fusion outfit Mahavishnu Orchestra higher than critics (“one of the best records I ever made, I thought”), his album with the American Beatle-influenced rockers Cheap Trick wasn’t up to much.

Oddly, Martin didn’t make his fortune out of his early association with the Beatles. Until 1965 he was on a salary at EMI until he quit to form his own company, Associated Independent Recording, and renegotiate a deal. Even then it wasn’t that lucrative, and he made most of his not inconsiderable nest-egg after the Beatles’ demise.

His AIR Studio in North London is one of the most sought-after in Britain and he also had -- until last year’s volcanic eruption -- a studio on the Caribbean island of Montserrat.

So “retirement” won’t mean slippers and pipe at home in Wiltshire. He is the director of various companies, gives lectures and speaking tours, there’s the television series -- but he is going to spend more time on his boat or playing snooker.

So “retirement” won’t mean slippers and pipe at home in Wiltshire. He is the director of various companies, gives lectures and speaking tours, there’s the television series -- but he is going to spend more time on his boat or playing snooker.

But now it’s time for Martin to go. An orchestra to rehearse, he says apologetically.

If he can be charming, he can equally be frustratingly but politely impenetrable.

Not that it matters, really.

In any analysis of his illustrious life, it is not what he said that will matter. It is what he did. And it is hard to imagine that anyone -- especially during those crucial years in the 60s -- could have done it better.

Sir George Martin died in March 2016. He was 90.

post a comment