Graham Reid | | 10 min read

Few people could claim to have been as publicly reviled, ridiculed, misunderstood and misrepresented as Yoko Ono. As her husband of 12 years John Lennon once remarked, she was “the most famous unknown artist in the world. Everyone knows who she is, but nobody knows what she does.“

And the little that people did know during her heyday in the Sixties they didn’t much care for. Yoko was just more than a little weird … and did little to discourage that opinion.

This upper-middle-class daughter of a Tokyo banker and his aristocratic, wealthy wife has a steel trap mind for business and would speak in childlike aphorisms of clouds and skies. Well before she met the most famous, respected, reviled and controversial Beatle of them all in 1966, she was publishing instructive, conceptual art pieces like: “Watch the sun until it becomes square” (Sun Piece, 1962).

That Ono -- educated at the exclusive Sarah Lawrence College in America and at Gakushuin University as a philosophy student in Japan -- was part of the influential avant-garde Fluxus arts movement in New York in the late 50s was quickly ignored when she met Lennon. She became sidelined as just another Beatle flake.

“We both sort of ruined each other [when we met],” she said recently of their respective careers.

When Ono thought of the individual as art statement she was genuinely interesting. But things could get very silly, too, as when she sent this contribution to a rock star cookbook which contained Rod Stewart’s typically boozy recipe: “Dream Soup: Put a lot of sunshine in a large bowl. Mix it with your dream of your future. Spice it with a pinch of hope and laughter …”

Ono was, however, courageous, both in the consistency of her art (and later music) and in the course of a life most would happily do without. She suffered three very public miscarriages, a number of abortions if Albert Goldman’s scum-sifting biography of Lennon is to be believed, lost contact with her daughter from a previous marriage, gave birth at 42, and five years later saw her partner take five bullets in his chest and die on their front doorstep.

It has been an interesting life.

On the phone from her home in the Dakota mansion in New York, the voice still has that childlike quality familiar from those numerous, rambling interviews of 20 years ago. But because she has always enjoyed the anonymity of telephones, she is comfortable talking about her recent rediscovery by arts observers and critics, rock musicians and music journalists.

Yoko Ono: The Reassessment? Now that’s an interesting concept. The re-emergence of Ono built to critical mass this year when the small but influential American record label Rykodisc released a six-CD Onobox set retrospective of her music. That’s two more discs and in more elaborate, informative packaging than EMI Records offered her rather more musically famous husband.

Ono’s rehabilitation actually began four years back when the Whitney Museum invited her to mount her own one-woman show. She says now she was initially very tentative and “expected to be knocked again” but eventually submitted a series of bronzes of her early sixties work. Bronze is, according to one of the show’s critics who found in favour of Ono, “the artist’s medium of commemoration, used to immortalise famous moments or the famous dead, as in monuments of deceased public figures.”

Put that to Ono, who exhibition included Untitled, a bronze of Lennon glasses, and she understandably sees it very differently.

“The Eighties was a very materialistic age, so in celebration and as a satire I made my objects in bronze. It was a kind of … Eighties statement.”

That exhibition was so successful it drew other invitations and while a collection of her films tours under the auspices of “the AFA, the American Federation of Arts or something like that,” she works on new projects. Her present Endangered Species work is, she says, “a strong comment on how things are going now in the world.” She won’t be drawn further.

A number of factors have allowed her time to pursue her long-interrupted career again, she says.

“I started to take care of the business when John was still here and after his passing I had a difficult 10 years doing that and cleaning up things. Now is a quiet time. I’m still busy but finally have time to do creative work.

“Sean was young too. He’s 16 now and starting to be very independent. A lot of women go through the same thing. They have to wear many hats -- mother, wife, career woman or whatever. One day they find the children are grown up and they have time to themselves. That’s where I am.”

Preparation of the self-commemorative Onobox has taken considerable time in remastering the material, but has also offered her the most reward. Musicians have been queuing up to pay tribute to the uniqueness of her vision -- and her sheer persistence in the face of critical derision and indifference.

Kurt Cobain of Nirvana calls her “the first female punk rocker”, David Bowie and Eric Clapton have been longtime fans, Kate Pierson of the B52’s interviewed her for Rolling Stone and Donita Sparks of L7 (who sampled Ono for a track on their Brick are Heavy album) says women musicians should rescue their heroines from obscurity or, in Ono’s case, “disgrace. She was [expletive deleted] ahead of her time.”

Rehabilitated long after her critics and detractors have lost their pungency, Ono enjoys her new profile but offers a slightly disingenuous assessment of her place: “I’m just another artist trying her best to convey joy and some pain. In the contemporary era most artists don’t get persecuted or discredited or ignored like I did, but in the good old days Ibsen got flak for A Doll’s House, van Gogh was ignored.”

Ono may display naivety or nerve putting herself in such company, but she has a point. Her artistic career in the late 50s anticipated the New York “loft scene” and she hung out with the likes of composer John Cage. She was a figure of some profile and notoriety in the New York/London art scene. And she approached her primal, eccentric, confrontational and sui generis music the same way. Her films (the notorious travelogue of bottoms; a 52-minute, super-slow piece of Lennon smiling, another of his penis becoming erect) have been superseded by video and MTV. .jpg)

So it has been the music which has undergone the most severe reappraisal since the release of the 105-song Onobox, over which Lennon may hover like a ghost but in which he plays little part.

The Onobox re-presents Yoko Ono, not the wife of a famous man, and that was important to her. One record company had approached her in 1990 just before the 10th anniversary of Lennon’s murder wanting her music “but anything with John on it, a guitar lick or whatever.” She instinctively shied away, but when approached by Rykodisc, who made it clear it was her they were interested in, she “still had cold feet because I was used to being knocked and thought, why open that Pandora’s box again? I wasn’t eager.”

She offered to prepare a nine-CD package, modified it to eight, then accepted the still-ambitious six-CD project. Compiling the project, which includes much previously unreleased material, was harrowing, she admits. Hers is a life more notable for its pains than pleasures and her work was always largely autobiographical.

It was easy up until the central disc in the set, Kiss Kiss Kiss, which opens with the song long recognised as her finest moment, the industrial disco and eerie talk-piece Walking on Thin Ice, tapes of which Lennon was carrying when shot. Up until then she was just having fun: from then on, it was devastating, she says.

But being back in recording studios also stimulated her and in January she started recording again. The project was interrupted by another art gallery commission.

“I’m going to finish it, but don’t expect it will be completed this year. It’s a new medium I’m thinking of, which is why I don’t think it could just come out as a record. The new songs are about 15 minutes long and have a different texture from a three-minute piece. But I would say they fit into a rock context.”

Ono’s evasiveness about her current works is understandable. At 59 she can hardly expect to have the same profile she once had. She may not want it, either, but it is noticeable that her works have largely been retrospectives. If there is a place for her conceptual art or recordings in the 90s, it is hard to imagine where.

As curator of the Lennon archive and estate manager, she is on more sure ground although even here her role is under scrutiny. When she went to London four years ago to promote the Imagine film documentary of Lennon’s life, launch an expensive books of stills from the movie and preside over the opening of a Lennon art exhibition, Gavin Martin in the NME tartly pointed out: “that is -- a film she didn’t make, a book she didn’t write and an exhibition that isn’t hers.”

Albert Goldman’s scurrilous, actionable, shoddily written but perhaps largely true The Lives of John Lennon book at the same time painted Ono as the Dragon Lady/Witch Bitch who ran their marriage as a power play and frequently used emotional torture to retain dominance. Ono cannot escape controversy, it seems.

Yet credit must be given for her astute management of the multimillion-dollar estate and the cautious, professional drip-feed of posthumous Lennon albums (a four-CD set of unreleased material before Christmas, she says; next Christmas, says the record company) which has kept the spirit alive.

“That’s another thing, isn’t it?” she laughs when asked about the extensive Lennon photo-archive. “I’m a mother and a businesswoman ….. and I’m trying to stay calm and do my best. I’m not slowing down but trying not to rush things, either. But the response to the Onobox and other things has been very encouraging.”

At times she repeats her regular refrain of “I wish John were here to see this.” That smacks of calling up their past association which she most often says she wishes to distance her work from. That she has manipulated the Lennon legacy is well known.

In 1985, amid enormous security, she and Lennon’s two sons made what Q magazine scathingly called “another low-key appearance” and noted their much-publicised visit to Liverpool “was ostensibly to show Sean around his father’s hometown” but “neatly coincided with the release of her solo album Starpeace.”

She isn’t above selling the family jewels, either, and Lennon’s Instant Karma of 1970 now appears on a Nike advertisement, and his Beautiful Boy, written for son Sean, was sold to a Japanese cosmetics firm. It sells shampoo now.

In life Lennon vehemently opposed such commercialisation of his and Beatles music and, as Jay Cocks noted in Time in ‘88, when the Beatles agit-prop, Lennon-penned Revolution was sold to Nike, “Mark David Chapman killed [Lennon], but it took a couple of record execs [and one] sneaker company to turn him into a jingle writer.”

Then, as now, Ono defends this use of the music. It isn’t for money, she says of the Instant Karma sell-off. Proceeds went to the United Negro Educational Fund and “I think John would have seen how his song would have that kind of use, to help young children go to school”.

“But also Beautiful Boy was never a single, so I couldn’t say it was previously successful. It was never considered as a single before and now in Japan it’s number one,” she says, with a slight sound of self-satisfaction. (Not according to official charts, but let that pass.)

“And likewise Instant Karma. The record company would never consider releasing it as a single, but because of the ad they have it is top 10 in Europe. (Again, no evidence of that, but no matter.)

She talks of a whole new generation discovering Lennon’s music and it’s all for a larger purpose. She takes off on a tangent.

“The more we do these things with John’s songs, the more there’ll be a good vibe out there. The other side of the story is the war industry is still very big and constantly generating bad vibes. I think the peace industry has to work hard generating positive vibes.

“It’s a business situation I have to overcome. If I didn’t do anything about John’s music, it would eventually end up in a library with classical music. But John is out there right now.”

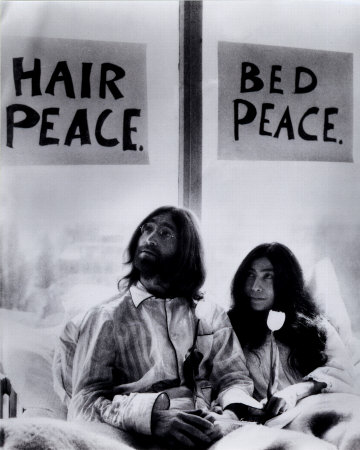

That yin-yang of neo-hippie idealism and Yokonomics is typical. She had her own life and perspectives but most often they have been determined in terms of her more famous partner. Theirs became the great public spectacle. At times they literally stook naked before the world and accepted -- indeed set themselves up for -- its derision. Yet both were curiously private people.

That yin-yang of neo-hippie idealism and Yokonomics is typical. She had her own life and perspectives but most often they have been determined in terms of her more famous partner. Theirs became the great public spectacle. At times they literally stook naked before the world and accepted -- indeed set themselves up for -- its derision. Yet both were curiously private people.

Talking of their withdrawal from the world in the mid-70’s, Rolling Stone writer Chet Flippo noted they never held a party in their apartment. Lennon had no more than 10 names in his address book (mostly lawyers) and “John never had to change his phone number like most celebrities.”

Ono makes time to talk about her career and the critical reassessment going on, but also says she has very little social life.

“I had a busy one before I met John but in the long years with him I got used to not having one,” she says quietly. “Just working, I like that. I’m a workaholic and if I’m doing that I’m very happy.

“I like to walk … but that is it.”

Yoko Ono -- polite, quiet, charming, shrewd and efficient. And seldom relevant. Even to these times she was supposedly so far ahead of. The living reminder of a shattered double fantasy. A petite, reclusive millionairess with a promising future behind her.

Yes, it has been an interesting life.

post a comment