Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Among the tickets touts barking at the crowd outside the Sydney Entertainment Centre before the Paul McCartney concert, the scalper with the XXOS beer gut wrapped in a small-men’s T-shirt stood out.

While others on this raw edge of the market economy were offering $130-a-ticket, the swollen T-shirt was nasally hawking “tickets in the front row”.

No one believed him, and nor they should because, according to the media machine, tickets for McCartney’s two indoor shows had sold out within 10 minutes of going on sale four months previously.

And those in the front row didn’t look they were ever going to flog off prime seats for this return of one of the few true legends that rock can claim.

Not that many people used their seats anyway, because from the first bar of Drive My Car, which opened the two-and-a-half hour show, the whole of the ground floor was on its feet, swaying to the sound of McBeatles/Wings/McSolo Years material as laser lights cut the air.

As rock shows go, this was one of the best: it had its own sense of history, a measure of cynical comfort in the familiarity of the music and -- most surprisingly, given McCartney is now 50 and the album before the current, typically indifferent Off The Ground was an orchestral and choral oratorio -- it had energy to burn.

And the first face recognisable on this night when a Beatle had retuned to Australia for the first time since 1975? A youthful John Lennon projected on one of the split-screen backdrops as footage flicked up scenes from A Hard Day’s Night and the famous Shea Stadium concert of 1965 amid images of those innocent Swinging Sixties.

“We might have missed the Beatles but for Paul McCartney,” Irene Wardle, who attended the concert with her daughter, told the Daily Telegraph Mirror. “It’s great that we both like the music but it’s pretty easy to understand when you consider how popular he is.

“After all, the sounds of the 60s are timeless really, aren’t they?,” she added rhetorically.

And as the opening chord of A Hard Day’s Night crashed through the sound system and the decades between then and now were dealt to in a slightly perfunctory manner by the video presentation, it seemed as if McCartney had arrived in the 90s without being through the 70s and 80s.

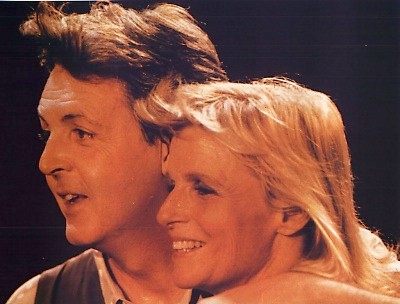

Yet when McCartney and his cracking band -- wife Linda rather more decorative than functional however -- took the stage amid deafening roars, it was undeniably his night.

Despite the high Beatle-count (all of them identifiably his Beatle songs and including treats such as We Can Work It Out in a brief “unplugged” section), he pulled out some unexpected material: the brittle and heavily Lennonesque Let Me Roll It; a choppy poppy nod to his own roots in Elvis’ Good Rockin’ Tonight; and a Bo Diddley-style reworking of I Wanna Be Your Man which caught the audience off-guard.

After letter-perfect treatments of All My Loving and his own Comin’ Up, this rethought Beatles/Stones chestnut was a courageous and successful at attempt at investing new life in a very old song which he and Lennon had knocked off for the young Stones -- then tossed at Ringo for their own version.

But some in the audience seemed more prisoners of their past than the singer . . . . Except for a teenage headbanger in the front row who recognised rock’n’roll liberation when he heard it and -- despite a thousand cynical reasons why he shouldn’t -- just went for it: him and Paul together.

It was a bizarre, magical moment made more resonant by seeing a sixtysomething couple four rows back singing every word.

McCartney concerts have that broad success these days: here’s a man whose audience is a publicist’s dream. He really does pull the generations together and, in the lobby afterwards two Wayne’s World clones in Faith No More t-shirts stood alongside a mother and daughter at the tour merchandising stall which sold tour programmes, shirts and caps.

And McCartney plays to the knowledge that a sizeable proportion of his audience is younger than Yesterday.

He banters with the crowd from behind a psychedelic piano as he introduces another “oldie”.

“You weren’t there,” he quips and points accusingly at some teen in the crowd who is baying from half a dozen rows back. “I was . . . I just don’t remember it.”

McCartney is the consummate showman. His self-effacing manner and manifest ordinariness -- no matter how much a façade, and if they are he has kept them up for a long time -- are endearing.

Yet ironically he looks most happy when surging through the rock songs, with guitarists Robbie McIntosh and Hamish Stuart setting a punishing pace.

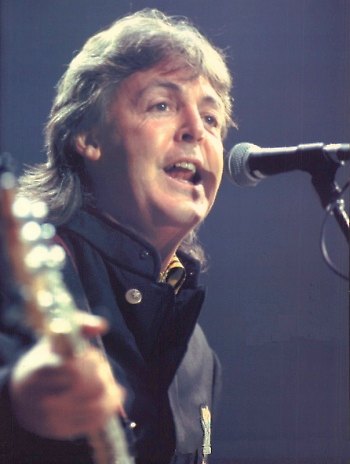

McCartney, salt’n’pepper hair falling well below his collar, swivels and dives, punches his bass, and looks for all the world like a man whose chief pleasure in life is making rock music, not the pop he has become associated with.

The long St Pepper coda and Band on the Run peel away the years from him more than his audience. His thunderous Live and Let Die, “which another band has covered” is almost life-threatening in its explosiveness. “That woke you up,” he laughs.

The new material slumps by comparison but the staging carries the moment. If he sings one too many from Off the Ground (and he only sings six) the set is paced to speed up Beatle-heavy in its closing overs.

And he isn’t called Mr Thumbs Aloft by the British press for nothing. If there is any message beyond his frequent public espousals of environmental and animal rights issues it is one of cheery, good bloke optimism.

His “think globally/act locally” message which crams the handsome tour programme is mainstream thinking these days and therefore uncontroversial. It’s no less a message for that, and the McCartney’s longtime support of Peta (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) may be a natural corollary, but has somehow branded them as part of some loopy-Left veganism.

As one of the world’s richest entertainers, McCartney -- whose first Wings album Wildlife in ‘71 addressed animal cruelty it should be noted --probably couldn’t care less. But he does speak out about these issues, although on this tour he came to the point of speaking less and less. Interviews, especially for print journalists, seemed hard to obtain.

The MPL machine (McCartney’s company) runs a tight ship, although the man himself seemed happy enough to do the occasional radio or television airshot.

Aggrieved print journalists attribute that to the soundbite syndrome. Radio and television don’t probe in the same way as eyeballing print journalists who want an hour to ask The Hard Questions . . . Whatever they may be.

But get to Paul McCartney, Mr Thumbs Aloft, and what are you going to ask anyway?

Why does he still do it? That is answered unequivocally by the show.

About that Illustrious Past? “So it was sex and drugs and rock’n’roll then?” That was recently tried with charming naivety and found wanting. It also made for woeful and cringe-inducing television.

The marijuana busts that the McCartney’s have endured? “Paul’s an amazing guy. He just smokes his joints and whistles his way through life,” said Harry Nilsson a decade ago.

The present? Hmmm . . . Rock critic Charles Shaar Murray faced that one back in ’75 when he was lined up for an interview in the wake of the less-than-successful follow-up to Band on the Run, the weak photocopy Venus and Mars.

“It ain’t easy troops, “Murray wrote, “because I’m as full of Beatle-awe as the next bozo who was 11 when Love Me Do came out and who queued for two and a half hours to see the very first showing of A Hard Day’s Night . . . [but what am I] going to tell McCartney right up front about how much I hate his album and by extension him for making it . . .”

A similar situation exists today with Off the Ground.

But as Q magazine noted in its review, McCartney did everything his critics ever wanted: he made a considered, artful album, made videos, toured and hustled as hard as any aspiring beginner. It was a more than creditable album, it was almost a great Paul McCartney record.

It was called Flowers in the Dirt and it came out three years ago -- and went all but unacknowledged by the greater public.

Off the Ground is a retreat from that position and at the concert -- with the notable exception of the impossibly catchy Hope of Deliverance -- the current songs don’t hold up.

Perhaps it would be worth asking McCartney how he feels about making a great album and having it ignored. Could he care?

At the end of it all, you have to concede that getting McCartney talking about his music really doesn’t matter anyway. The broad audience in front of him couldn’t care less. They sway tolerantly through the B-grade Chuck Berry manoeuvre of Get Out of My Way from the new album, stand mute in the face of the disarmingly unfashionable opening couplet of Peace in the Neighbourhood (“best thing I ever saw/was a man in love with his wife”), and receive the purportedly uplifting message of C’mon People with quiet indifference.

No one is seriously at the Sydney concerts for Off the Ground. That's just another album on the long journey: another Back to the Egg, Pipes of Peace, Press to Play . . . Another Paul McCartney album.

A few years ago McCartney said that what he likes about the music he has written since the Beatles is that it is mostly undiscovered, blanked out.

To a small degree that is true. He crafted beautiful, ignored songs like Here Today about the late John Lennon, and wrote seriously wild rockers like Girls’ School and Junior’s Farm.

But as he tours on the back of another indifferent album he feels no need to introduce a receptive audience to that material. There is nothing from Flowers in the Dirt or even half a dozen albums in the 80s.

Does that matter particularly? Not a jot.

Paul McCartney has a back-catalogue of McBeatles/Wings/McSolo Years that is awe-inspiring in its scope (if not always its depth) and which even a show as long and as exciting as this New World Tour cannot even begin to encompass.

McCartney and his band invest the familiar songs such as Paperback Writer (on Hofner violin bass held high like an icon), Fixing a Hole and I Saw Her Standing There with such a sense of urgency that they legitimise the material by denying their sentimental value. He plays them as if they had just been written.

He is brought back for a long encore. The man who wrote himself into the history of Western music by the time he was 25 reaches out and touches his audience once more. There is some strange poetry in “the movement you need is of your shoulders” which goes directly to the heart of the capacity crowd.

The musicians bow for the last time, the thumbs go aloft, he is sweat-drenched and has his arm around his wife as he leaves the stage to go . . . to go wherever someone like Paul McCartney goes after such a night where collective dreams and audience nostalgia have briefly co-mingled with the present.

post a comment