Graham Reid | | 10 min read

At 55, Astrid Kirchherr still loves rock music and listens to it every day: The Beatles, the Doors, Bowie . . . “and Prince, he’s such a genius -- if he just wouldn’t wear those stupid clothes! I always wanted him to look serious, young and sexy. But he dressed like an old prostitute in drag.”

Kirchherr laughs briefly -- the only time in this serious conversation that she does -- then seriously resumes the discussion. She loved punk bands too. And to hear her talk of punk and its hard-edged look makes sense because for a brief but extraordinary period in her life 30 years ago she was taking photographs of other bands who were rough around the edges, dabbling in pills and excess, thrashing out loud music in dank cellars and clubs, and dreaming of fame.

For some it never happened: Rory Storm and the Hurricanes are just a footnote in history now, But for others, notably the band this woman was closest to, the rewards and price of fame came in a way the world hadn’t seen before.

Astrid Kichherr’s friends were the young John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, pre-Ringo drummer Pete Best and -- closest of all -- Stuart Sutcliffe. The band carried the name three of them would take to the world, the Beatles.

It was Hamburg 1960 and the city -- much like the Liverpool the Beatles had left behind -- was a bomb site. Kirchherr recalls her first visit to Liverpool in the company of Sutcliffe and being struck by the similarities between the two cities: both ports, both still recovering from the war and both full of young people searching for something as the new decade opened.

For the upper-middleclass Kirchherr and her student friends in Hamburg it had taken the form of existentialism and Jean Paul Sartre, the Juliet Greco look, and dressing in black.

For the working class, unemployed Beatles it was rock’n’roll from America, James Dean (to whom Sutcliffe bore an uncanny resemblance) and, coincidentally, dressing in black.

When Kirchherr walked into the Kaiserkeller club in Hamburg’s notoriously sleazy St Pauli District that night in October 1960 she couldn’t have known her life was about to change.

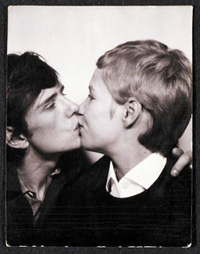

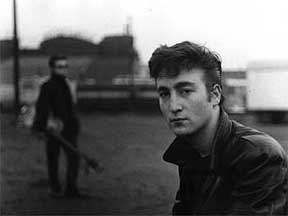

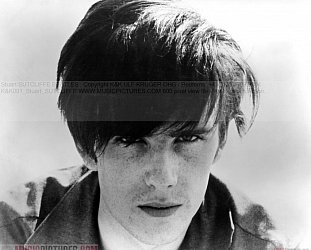

It was there she first saw the Beatles, “fell in love that very first night” with the silent, good-looking Sutcliffe (right), and began taking stark and memorable photographs of these young men from Liverpool.

But within two years it had all changed. Sutcliffe -- a promising artist with whom she lived for a brief time -- was dead at age 21 from cerebral paralysis, the remaining Beatles were beginning their relentless and rapid rise to fame, and Kirchherr was recovering from her grief and trying to rebuild her career as a photographer taking shots of other bands who were flooding into Hamburg.

Of all of the pictures of the Beatles which have emerged over the past three decades it is Kirchherr’s which have the most resonance.

“You have to remember the time,” she says from Hamburg where she now works part-time for a music publisher.

“I was very influenced by my teacher Rheinhardt Wolf who I was acting as an assistant to, and the whole French existential thing. And I only ever worked in black’n’white. I can’t stand colour photography even today.

"To me a black’n’white picture is much more artistic and you can play with it more when you are a portrait photographer. You can show what is going on in someone’s face and soul.

“And it is a serious job being a portrait photographer which is how I saw myself. I always took my friends seriously in what they were doing. For me the music of the Beatles then was serious and very, very serious art. So I couldn’t take a picture of John laughing his head off or pulling funny faces because he was a serious artist, even when he was only 20.

“It broke my heart when I saw some of those later pictures when they were just in the studio grinning. I guess that was the price they had to pay and maybe that’s also why my pictures are not old-fashioned today.

“I respected them even though they were young, wild boys from Liverpool -- because they weren’t just that to me.”

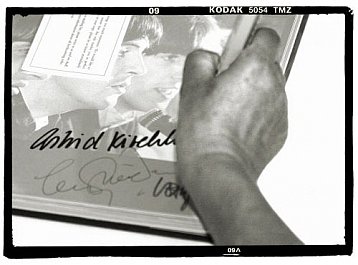

Within Beatle circles the name Kirchherr is well known. Her pictures have been given wide circulation in magazines over the years although she says it was only five years ago she first received any royalties from their reproduction.

But today her name is steadily entering the world of pop mythology through publications of books and, most visibly, the movie Backbeat which traces the difficult three-way relationship between herself, Sutcliffe and Lennon during those Hamburg days.

For many years Kirchherr has been reluctant to discuss her relationship with Sutcliffe but with Backbeat and its paperback companion by Alan Clayson and Sutcliffe’s sister Pauline, she has been more forthcoming.

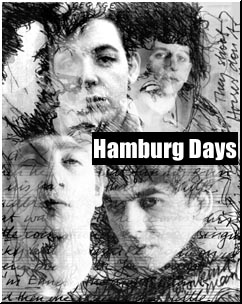

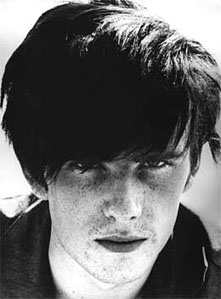

However it is her groundbreaking photographic work -- taken on a Rolleicord camera -- which is perhaps more noteworthy. Those photographs of the tough young Lennon, the shy Harrison, a lean-face McCartney and the high-cheekbones Sutcliffe have been put together in a touring exhibition and will -- with additional pictures by Jurgen Vollmer* (whose work was used for the Lennon Rock’n’Roll album), plus drawings and painting by Klaus Voorman (a Beatles sidekick who drew the band’s Revolver cover) -- be gathered in a limited edition book entitled Hamburg Days.

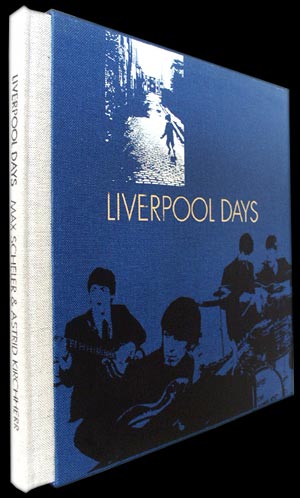

Already published is its companion volume Liverpool Days which gathers photographs taken in the streets of Liverpool in ’64 by Kirchherr and fellow-photographer Max Scheler.

With a limited edition printing of 2500 copies (numbered and autographed) through Brian Roylance’s specialist publishing house Genesis, Liverpool Days follows the pattern of previous Genesis publications such as George Harrison’s limited edition autobiography I Me Mine and the Blinds and Shutters collection of works by the 60s photographer Michael Cooper.

Kirchherr met Roylance when he asked her to sign copies of Blinds and Shutters, and both Liverpool Days and Hamburg Days grew from there.

“I haven’t actually got hundreds of Beatle photographs because I didn’t go around taking pictures all the time. The ones I did were all thought out. I have lots of portraits of other people and some unfamous musicians,” she says referring to the likes of the Undertakers and Merseybeats who appear in Liverpool Days.

“But not so many of the Beatles.”

The book collects photographs from a visit to the Beatles’ hometown and they capture another world, one closer to that shown by wartime photographers than a city about to leap into the swinging Sixties. But the signs were already there.

“When I first went there was a very high crime rate among the young and unemployment was very high, and it was very rough and kids were just hanging out in the streets. And there were gangs -- it wasn’t very pleasant even though I loved Liverpool and the people.

“When I went back with Max there was hardly any crime any more because all the youngsters got guitars and formed bands.”

That impression was confirmed when photographer put up a notice in Frank Hessy’s music shop -- where all the bands, Beatles included -- bought their instruments. Offering one pound to any musician who would turn up on the steps of St George’s Hall at noon on the following Saturday. Three hundred and fifty did . . . And the photo of them is in Liverpool Days.

Kirchherr also notes that the audience for the Beatles and Liverpool bands was much younger in Liverpool -- “girls and boys from age 10 to 15” -- whereas in Hamburg they played to an older student audience as well as drunks, sailors and street people in the rough clubs.

In Liverpool Days Kirchherr is photographed outside the famous Cavern at the head of a queue of a hundred or so people half her age.

The previously unpublished photographs of the Beatles -- then busy filming A Hard Day’s Night - are less impressive, perhaps their currency worn thin by the familiarity of the faces. They are no longer the leather-jacketed, sullen figures she knew from Hamburg either, but refashioned into suits and ties.

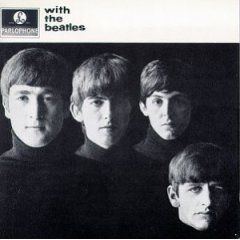

But the works do capture a period and an image. And Kirchherr’s stylistic signature -- figures captured half in shadow -- was to be appropriated by British photographer Robert Freeman who later shot the iconic With the Beatles cover in the manner of her Hamburg shots.

“I met Bob Freeman once,” she says, “and I like his work. His other pictures are great but I’ve got this idea, and I don’t know if it’s true, that the Beatles told him to take a picture like Astrid used to do because that half-lit idea was not his style at all.”

“I met Bob Freeman once,” she says, “and I like his work. His other pictures are great but I’ve got this idea, and I don’t know if it’s true, that the Beatles told him to take a picture like Astrid used to do because that half-lit idea was not his style at all.”

Yet ironically it was Freeman and not her who went on to become the Beatles’ most famous shutter-snapper: he did the album covers for A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles For Sale, Help, Rubber Soul, Lennon’s two books and numerous intimate shots (collected as The Beatles: A Private View in 1990) as well as that famous With The Beatles cover which he says was “an extension of my black’n’white jazz photographs”.

For Kirchherr however, her friendship with the Beatles during those ragged, formative years in Hamburg wasn’t something she could, or wished to, cash in on.

By giving the Beatles themselves copies of all the pictures she took they eventually found their way into the hands of others and were widely reproduced, most often without her receiving credit let alone financial recompense.

Although also credited with creating that famous mop-top hairstyle when she encouraged Sutcliffe to wash out the grease and brush his hair forward in the manner of Jean Cocteau (albeit considerably longer), she all but faded from sight over the years.

She felt cheated by not receiving any money from the reproduction of her work “so I didn’t give any interviews to the press because they never wanted to know the truth about my relationship with the Beatles. They had their own story -- so why should I talk to them?”

Naturally she was suspicious of Backbeat director Ian Softley when he approached her to make a movie his movie about Sutcliffe, but after initial no-promises meetings she was happy to contribute to the film and now admits enjoying seeing her life portrayed with such sensitivity.

As for her photography, that went long ago. By the end of ‘64, the year of Freeman’s With The Beatles cover, and after her visit to Liverpool she had given it away saying she had lost confidence in her abilities and was wary of the more shady aspects of her profession.

She was briefly a barmaid, then found her way into working for a music publishing firm, the career she quietly pursues today and won’t be drawn on.

Kirchherr recalls that brief period in her life without sentimentality but with some sadness at the losses she suffered: Sutcliffe whom she was to marry after he finished a painting course at the Hamburg State College of Art was her first.

Distance allows her a new perspective and she says she enjoyed reminiscing with the actors in the Backbeat movie.

As for the remaining Beatles? “I saw Paul about two years ago when he came her on tour, and George I saw the same year. Although I had the flu he came round and we had a cup of tea and a chat.

“Ringo? I was never that close with because he wasn’t in the group when they came to Hamburg at that time. And John, the last time I saw him was in the 60s.

Both Paul and George have copies of every picture I had and I suppose John did too.

“John was a musician, there was no doubt about that. Stuart was an artist, there was also no doubt about that.”

And with a touring exhibition of Sutcliffe’s abstract works from that short but fruitful Hamburg period when he worked in the studio above Frau Kirchherr’s house there is a revaluation of his work with artistic circles.

Art historian Lord Clark considered him “a most talented artist. What a tragedy that someone so beautiful and gifted should have died.”

Poet Adrian Henri, speaking at Sutcliffe’s retrospective in 1990 noted that the paintings “look as good today as when they were painted, and as relevant. His posthumous reputation certainly doesn’t need the glamour of his former band to enhance it.”

Such belated recognition delights Kirchherr, who admits to only having a couple of his paintings at home. She lives alone now.

“But you know, those things happened 35 years ago -- you must remember the time. There was this weird position we were all in as far as things like sexuality was concerned . . .and there was this huge guilt among young German people after the war.

“But there was also nothing there. Everything for us started then: rock’n’roll, fashion, art . . .

“Everything for us began then.”

Astrid Kirchherr died in May 2020. She was 81

post a comment