Graham Reid | | 9 min read

His letters back home don’t tell the whole story. But such letters seldom do. He says there are plenty of girls “but none of us can be bothered” and that he is “not the happiest man alive. It’s now my seventh week here. I came here for a reason I do not know. I have no money, no resources, no hope . . .”

The reality was, of course, something quite different: sex and drugs and rock’n’roll in fact.

Five young men -- the youngest still only 17 -- away from home and playing in a band, ingesting huge amounts of alcohol and amphetamines, getting regular treatment for sexually communicated diseases, thrashing out rowdy music on a small stage . . .

It was a time of raging hormones and raw harmonies, Chuck Berry and cheap bennies. Yet, enjoyable though that was, the letter writer was deeply unhappy. He was a musician by default who couldn’t play the bass guitar he was saddled with and whose natural inclination was to painting. And he’d had enough.

“I’ve decided at Christmas I pack in rocking and join the club again,” he wrote to an old art school friend in October 1961. “You know, the old jeans and sweater gang with a pencil and sketchbook. I decided that if I get back, I might yet be able to make something of myself. When I come home at Christmas it’ll probably be for good, also without guitar probably. I’ll sell it if I can.”

But he didn’t get home. He fell in love and then, within 18 months, he was gone. A promising artist dead, but a small part in a larger legend born -- for the letter writer was Stuart Sutcliffe, a bit player in one of the great rock stories of the 20th century.

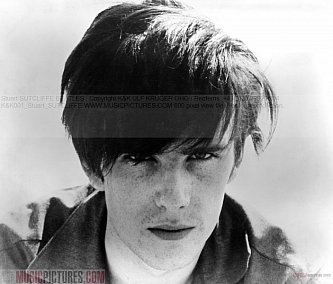

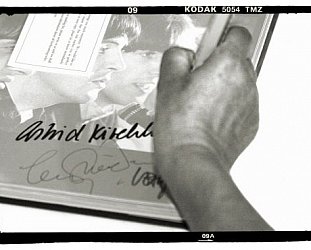

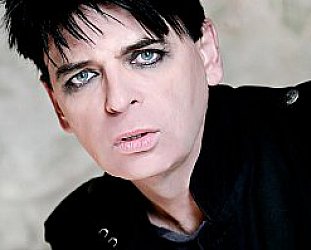

Sutcliffe was the bass player in the Beatles during those sweaty Hamburg nights on the cusp of the 60s and for more than three decades has been a murky figure in Beatle legend: the infamous dead one who never recorded with the group but whose relationship with Hamburg photographer Astrid Kirchherr (right) meant his sad, sullen image would stare out of pages without context.

For him death casts a cloak of mystique over a talent that never had a chance to develop. And not that of a musician, but as a painter whose abstract works -- immature but with a visceral power -- have subsequently been given gallery showings in places as far apart as Japan and his old hometown of Liverpool.

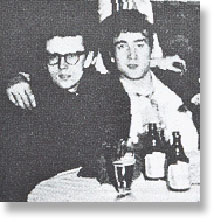

Stuart Sutcliffe was John Lennon’s best friend at Liverpool College of Art. When he sold a painting, Lennon convinced the unmusical Sutcliffe to buy a bass guitar and join his band. And so it was that Sutcliffe joined the formative Beatles alongside 19-year old Lennon, 17-year old Paul McCartney, 16-year old George Harrison and numerous pre-Ringo drummers. By the time the band secured a residence in Hamburg, Sutcliffe could play rudimentary bass and Pete Best was on the drum stool.

But Sutcliffe was always at heart an artist so when photographer Kirchherr and her upper middle-class Exis (existentialist) student friends took an interest in the scruffy working-class band from Liverpool, Sutcliffe was drawn by natural inclination into their circle.

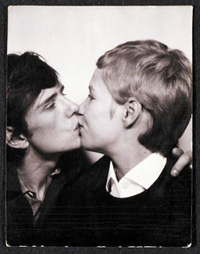

This much is the stuff of common truth, thereafter the relationship between Lennon and Kirchherr with Sutcliffe at the centre becomes the stuff of speculation. In later life, when he quit the Beatles, Lennon said that there came a time when everyone had to leave the football team and all the lads behind. He could say that as a man approaching 30, but when Sutcliffe was severing his ties with the Beatles and had moved out of the cramped backstage rooms to live with Kirchherr, the young Lennon was caught in a web of conflicting emotions. The love he felt for Sutcliffe was something the then-homophobic Lennon couldn’t articulate. And although he seemed reluctant to acknowledge it, he too was drawn to Kirchherr, an intelligent woman of the kind he simultaneously loved and feared.

It was a menage a trois of minds and passion with sleazy clubs as its backdrop and rock’n’roll its soundtrack.

This brief period in the lives of these three characters is at the nub of Backbeat, the movie by first-time director Iain Softley which re-creates the period with an eye for verisimilitude.

The Cavern in Liverpool, German clubs and the attic room above Kirchherr’s Hamburg home which Sutcliffe used as his studio have been re-created down to the smallest details after conversations with Kirchherr who first met the British director 10 years ago when he approached her about doing a movie about Sutcliffe.

“I was very suspicious, but he sounded very nice so I met him and he had a lot of honest enthusiasm about Stuart and his work,” says Kirchherr today from her home in Hamburg.

“I still wasn’t sure if he wanted to put Stuart in front of something just to get a story about the Beatles . . . but we kept up contact for about three years and he finally came up with a script and I saw that I could trust him. He wanted to do a film which was about Stuart and not just something Beatle-ish.

“But to put my life story and my love story out is very difficult. But I was very happy with the actors. I loved Ian Hart who plays John Lennon and Stephen Dorff who plays Stuart. It was easy thinking about Sheryl Lee who plays me but I felt much greater responsibility to the characters of John and Stuart because they are not here anymore and couldn’t complain. I had to be very careful about that part, putting them in the position they deserve as intelligent and humorous young men who were full of energy and talent. I think, thankfully, that comes through in the movie.”

Softley’s Backbeat is not the first film to address this pre-Fab Four part of the Beatles legend -- that honour belongs to the cheap The Birth of the Beatles from 1979 -- but Backbeat, largely because it shifts attention away from the Beatles and onto the three-way relationship, is the more successful. It has the advantage of strong casting and a sense of energy that elevates the story beyond being just another slice of Beatle-lore.

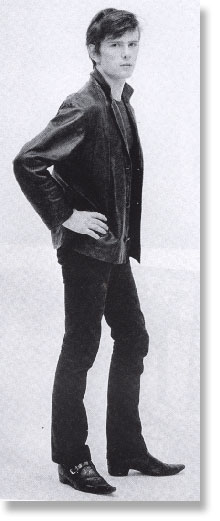

Actor Ian Hart reprises his Lennon performance from The Hours and the Times (a minor work by Christopher Much about the relationship between Lennon and Beatles manager Brian Epstein) and the American Dorff effectively drops his accent for passable Scouse. He also bears a strong physical resemblance to Sutcliffe who favoured the James Dean moody-in-shades look.

“There were so many similarities between Stephen and the young Stuart that it was very spooky for me,” says Kirchherr. “I was 24 when Stuart died, but when a tragedy like that happens you try to push the sadness away because you are selfish because you are so young. So really it did me good to reminisce the memories and the time for myself when this movie came up.”

Sutcliffe’s death from a brain haemorrhage -- variously attributed to a fight in a Liverpool bar or, less likely, a punch-up with Lennon -- doubtless robbed the world of a nascent artistic talent and shattered both Lennon and Kirchherr. Lennon turned his sadness into rage.

As author Alan Clayson and Sutcliffe’s sister Pauline point out in their biography Backbeat: Stuart Sutcliffe, The Lost Beatle, incidents of Lennon kicking a drunk in the face from the stage, delivering foul-mouthed sermons in bars and urinating on nuns from a window all date from April 1962, the month Sutcliffe died. Kirchherr went within herself, withdrew, then slowly resumed her career in photography. But by the end of ‘64 -- the year the Beatles stormed and conquered the world -- she had given up her work. She never resumed it.

Kirchherr says that for discussions with director Softley she had to forget all the accumulated wisdom on the past 35 years and put her mind back to the more innocent time when she and the young Sutcliffe and Lennon were finding their way in a confused world pulling itself out of the aftermath of the war: “Everything which meant a lot to me like art and fashion and rock’n’roll started then for me. That made it so wonderful.”

And as the world of rock’n’roll has subdivided itself into marketing components and the Beatles are relegated to classic hits radio formats, the movie Backbeat offers a window onto a time when pop was a collective experience, more innocent than today, and born of a belief in its power rather than letting itself being be manipulated as a fashion or lifestyle accessory. And that perhaps also accounts for the on-going fascination with the Beatles, especially in America through which it is impossible to travel and not see references in newspaper headlines or on the nightly news to “a hard days night” or a “magical mystery tour”. Beatle-lore is endemic in the States.

At the time Backbeat opened in New York earlier this year the city was hosting an exhibition of Kirchherr’s photographs of the young Beatles, across town there was a theatre production You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away: The Ballad of Brian Epstein which focused on the Beatle’s manager on the night of the launch party for the band’s seminal Sgt Pepper’s album -- and in a theatre off Broadway there was Yoko Ono’s execrable New York Rock play (using Lennon’s and her music) about a British rock star who becomes famous, leaves his wife, moves to New York with his new wife and is shot by a street punk.

It mattered little that this was an astonishingly bad production (“it’s not autobiographical,” insisted Ono unconvincingly) it played to full houses -- until interval.

Beatle-fascination is everywhere today, 25 years after the band broke up. Margaret Thatcher and a thousand others have had their photograph taken crossing Abbey Road and Oasis got promo photos taken in Strawberry Fields, the area of Central Park near the Lennon-Ono apartment. Kurt Cobain was a fan, Wellington’s Brainchilds do Tomorrow Never Knows, both Alice Cooper and Gene Simmons say She Loves You changed their lives and the Breeders perform Happiness is a Warm Gun.

“Beatlesque bands embark on their own fab forays,” read the recent Billboard headline on the article about the Greenberry Woods and the Grays which also included Crowded House and the Posies in the magazine’s sweep of current Fab Four repeat-the-beat(les)-sounding groups.

The Beatles themselves are also far from silent. On November 30 a new Beatles album, The Beatles at the BBC taken from ‘63-’64 radio sessions, will be released. It’s a double-disc which has 30 songs the band never recorded for their official EMI albums. And then there is Free As A Bird, the Lennon demo which the remaining three Beatles have recorded keeping in Lennon’s guide vocals. It will see release when the extensive Beatles documentary series is completed and gets a screening on British television next year.

It’s expected there will be a collection of Beatles’ rarities to accompany the series -- and there’s talk that the Lost Lennon Tapes, the radio series of Lennon outtakes and demos, could also be released.

1995 could be a big year for the Beatles.

It is easy to be cynical about Beatle-obsession but regardless of the detritus of the myth (all those plodding George Harrison biographies), the music still stands.

From “I wanna hold your hand” to “I’d love to turn you on” took a mere four years, but was a light-year in terms of collective cultural experience,. The band redefined the nature and possibilities of rock music, opened doors which can never be closed, and left a legacy of music unmatched for its diversity, ambition and humour.

“They changed the world of music,” says Kirchherr stating the obvious that we sometimes forget. “There will be an interest in them for always. They were artists and always deserve to be taken very seriously.”

As Backbeat’s publicity banner says, “5 guys, 4 legends, 3 lovers, 2 friends and 1 band”. And by removing just one of those elements -- although publicity bumf allows for perhaps one “legend” too many there -- it’s possible that nothing today in music -- or even the landscape of popular culture -- would be as it is.

Backbeat is about where the beat began.

post a comment