Graham Reid | | 7 min read

The Rolling Stones:I'm Free (1965)

It’s probably a bit cruel to destroy people’s faith in myths -- like telling a six-year old the truth about Santa Claus -- but the reason there are so few decent autobiographies and biographies in rock music is simple: the central characters aren’t that interesting.

Being a musician at that fascinating interface of low art and high commerce doesn’t necessarily bring with it special powers of observation or an intelligence beyond that needed to make music.

That’s unfortunate because when those worlds collide -- as they do so often in rock -- there are bizarre, sad and sleazy stories to be told.

But the larger-than-life characters who command television time, magazine covers and the ear of half of the western world don’t often have much to say for themselves.

Try as he might, Alan Clayson couldn’t find anything in the life of Roy Orbison to make him sound even moderately interesting -- and this was a man who had sung alongside Elvis, Johnny Cash, George Harrison and Dylan along the way. And is there a decent Harrison biography?

It isn’t exactly reassuring either when Kerry Juby opens his biography of Kate Bush (subtitled promisingly as The Whole Story) with the less-than-startling news, “She is the nice girl of pop, the girl you want to take home to Mum. . . Wow, worra rager.

If biographers have been at a loss -- Albert Goldman’s grubby and hilarious literary autopsies of Elvis and John Lennon excepted -- then decent autobiographies have been even thinner on the ground.

Dave Crosby’s massive Long Time Gone was overlong but enjoyable, not for the decline into drugs and XXXOS trousers but because Crosby himself is a mischievous intellect.

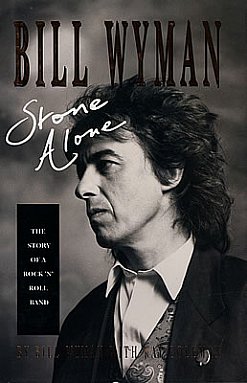

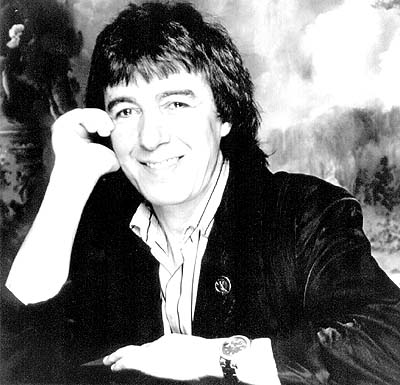

But when it comes to good recall and a story worth telling everything pales when compared with Rolling Stone bassist Bill Wyman’s Stone Alone. It is funny, obsessively detailed, fascinating in its trivia, oddly dispassionate and extremely weird because Wyman tells his story so straight.

It is also remarkable such a book should be written at all. Amidst the gear change of the generations in the Sixties (the book ends with the death of founder and then former Stone Brian Jones and the Hyde Park concert of 1969) and the psychedelic sociability of the time, Wyman quietly and often with disconcerting meticulousness documented it all.

While others went to parties, Bill went home, wrote up his diaries with methodical care for tiny detail, and pasted clippings in his scrapbook.

So Bill, what about that concert in Milwaukee on November 11, 1964 when the mayor said attending would be a sign of immorality?

“His broadside had the desired effect,” writes Wyman. “Out of the capacity of 6266 seats at the Milwaukee Auditorium only 1274 were sold.”

And Bill, what were the state of the old finances when you must have been coining it in after Satisfaction, Paint It Black, the High Tide and Green Grass compilation and Ruby Tuesday had all been hits?

“Though Mick and Keith had their song writing royalties, I can’t imagine that Brian could have been any better placed than me financially, and I certainly wasn’t rich: on 18 February my bank balance showed a credit of 26 pounds.”

When it comes to the small detail, Wyman has it all. And of course he was there for the big picture as well. Sort of.

Like drummer Charlie Watts, Wyman is the Stone who isn’t really a “Stone”.

He entered the band as a married man with a child and a steady job. He was seven years older than Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Keith Richards. His favourite musician was Stan Kenton, the leader of an often dull, middle-of-the-road big band jazz outfit.

“Brian, Mick, Keith and Charlie were not the sort of blokes I’d have chosen as mates if I hadn’t joined them in a group, “ he writes, and later says he rarely mixed with them socially.

Charlie went off to jazz clubs, Mick and Keith hit the hip pop clubs, and Brian took the drugs, got violent with his women and became increasingly paranoid. When Dylan wrote Ballad of a Thin Man with its refrain, “something’s happenin’ but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr Jones?” the sensitive and gifted Stone thought it was about him.

Wyman watched -- and recorded it all. Her preferred the quiet, orderly life and what set him apart was not only his age, but his modest -- not say poverty-afflicted - upbringing in London’s tougher streets.

When Wyman writes -- ghost Ray Coleman appears to play a mercifully small role on these pages -- it is of an upbringing shaped by the work ethic, regular beatings, evacuation during the war, a shared toothbrush at home and -- despite possessing an innate intelligence and propensity for academic studies -- being hauled out of school by his father before his GCE exams to help out the family finances. He got a job with a bookmaker.

The Dickensian squalor of his early life is reinforced in Wyman’s real name: William George Perks. Bill Perks of Beckenham, mate.

In that context it is easy to understand why Wyman -- and Watts who at 23 and another working-class lad with a proper job and still living at home with his Mum -- was vaguely disapproving of middle-class boys like Jagger, Richards and Jones.

They were playing the poverty game, living in cold-water flats and amusing themselves by gobbing spit on the walls and drawing in it.

And just as he flatly and with mild detachment tells of his own opinions, Wyman candidly offers an assessment of the internal politics of the band which was tearing itself apart even before they recorded their first single Come On, released in June 1963.

Wyman determinedly credits Jones as being the founder, early visionary and ruthlessly exploitative genius behind the group. But he also notes Jones was pathetically insecure, unscrupulous and very light-fingered.

Looking for your wallet? Brian picked it up.

But Jones quickly became marginalised by Jagger, Richards and early manager Andrew Loog Oldham. They discouraged his songwriting contributions and by ‘63 Jones simply couldn’t cope. He took early solace in booze and later drugs.

As his paranoia increased, the others dumped on him even more. It was a downward spiral -- all of which Wyman dispassionately documents. It’s almost like Wyman wasn’t even there as a player, simply the diarist of the disaster.

But there’s an innocence and quaintness about the period Stone Alone covers.

Pop writing at the time was stilted and gloriously unpretentious (Wyman naturally quotes numerous reviews of records and shows) and playing original material was not the issue it is today. Groups would have a residency in a club, build and audience and slowly drop in original material. The Sones played three months of Sundays at the Crawdaddy Club.

And through it all Wyman keeps taking notes. He records the drink and drugs (he disapproved of marijuana and even let a girlfriend go because she experimented with it), moans about Jagger sending flowers to Marianne Faithful and taking the money out of the Stones’ joint account for it, and records all the women he slept with.

And because there is the sense he is telling the story straight, there seems little reason to doubt his own claims about the women.

“In 1965 we sat down one evening in a hotel and worked out since the band had started two years earlier I’d had 278 girls, Brian 130, Mick about 30, Keith six and Charlie none. People always assumed that Mick, particularly, was very active sexually, but it wasn’t so in the Sixties. Mick and Keith usually stayed in their room writing songs and back in London they had steady girlfriends to whom they were vaguely faithful. Charlie was one hundred percent faithful to [his wife] Shirley. Brian and I were not faithful at all.”

When pianist Ian Stewart was dumped from the band before the recording of Come On (Stewart’s lantern jaw and short hair didn’t fit the image) Wyman tells of his relegation to roadie with the same odd detachment.

He may have been the Stone who urinated on the garage wall and sparked a controversy but he is still upset by accusations the group were dirty or untidy.

“We were all annoyed when we weren’t allowed in pubs or shops to buy cigarettes, or restaurants told us they were closed -- and then people following us would get tables,” he complains. “When we were tired and hungry that was too much. But hoodlums? Delinquents? The reality for me was having the money to at last to buy such things as a convector heater and light fittings for our home and having firm friends . . . My image might have been shaped and my life on tour was full of girls, but home life was pretty conventional.”

That kind of honesty is revealing and rare -- especially in books about rock which tend to be self-aggrandising and pompous. Rebellion is the politically correct attitude in rock culture but Wyman frankly admits he wouldn’t have minded the band being put in suits like the Beatles.

“It would have been a terrible mistake if we had gone along with it. Personally I felt that being in show business always meant looking smart, so the issue didn’t matter much to me . . .”

Bill Wyman might seem the unfashionably straight Stone but we have to amazed and thankful he was there. Her tells of the tragic figure of Brian Jones in decline; the self-serving and astutely career-minded Mick Jagger, and the schoolboy rebelliousness of Keith Richards. Charlie Watts is seldom quoted because, quite simply, Charlie has never had much to say.

“Most of the books written about us were written by people who didn’t know us at all, or only knew us for five minutes, “Wyman said last week in London.

“To them we were just a matter of drug busts and hit songs and women and urinating on garage walls. I didn’t want to write an expose. I just wanted to tell what the Stones were really about, as people and a group. I’m one of the few people who could do that.”

Wyman is too modest. He is the only one who could do that, and because there has been no other insider’s view like it, Stone Alone -- which recounts the boredom as much as the sublime moments -- is by definition, unique.

post a comment