Graham Reid | | 1 min read

Rufus Wainwright: Respectable Dive

In 2006, Rufus Wainwright presented two concerts at Carnegie Hall in which he recreated the legendary Judy Garland 1961 show in the same venue.

The subsequent album was hailed by many critics -- as were the concerts -- but you had to think in many instances it was by people who'd never heard the Garland recording.

There was perhaps an erring towards a favourable opinion because, after all, here was a gay man -- a gay icon in his own right -- celebrating a gay icon.

But, without dissecting the album too much, a fair hearing would say it often offered rather more languid, louche even, revisions of the material which were drawn from the Great American Songbook. But it earned him a Grammy nomination, which might more properly have gone to his studio album Release the Stars of the same year.

His next studio album was born of unhappy circumstances. All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu came after the death of his mother Kate McGarrigle and was a dramatic but demanding song cycle at piano which was extremely hard to take in concert as the drama compounded into melodrama.

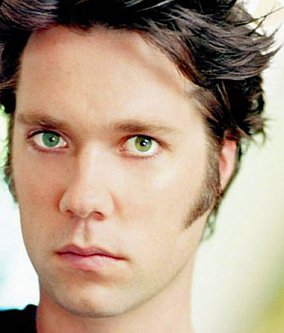

Wainwright -- articulate, funny and self-deprecating -- is also one who takes himself seriously, as witnessed by the limited edition, 19 disc box set House of Rufus released in 2011. For someone in his late 30s, this massive retrospective was akin to when Kenneth Branagh wrote his first autobiography Beginning at just 28.

Those who were understandably seduced by Wainwright's early albums but less smitten by the Carnegie Hall and Lulu releases probably missed his return to form with the rather more approachable Out of the Game in early 2012 (produced by Mark Ronson).

Those who were understandably seduced by Wainwright's early albums but less smitten by the Carnegie Hall and Lulu releases probably missed his return to form with the rather more approachable Out of the Game in early 2012 (produced by Mark Ronson).

He drew on pop influences (Bowie, Elton) as much as cabaret, offered lovely autobiographical songs such Montauk directed to his daughter (singing about her two dads, Wainwright married Jorn Weisbrodt at their home in Montauk in August 2012) and seemed to rejoice in the pop format while weaving typically smart lyrics across musical settings which also referred to Fifties ballads (the lazy Respectable Dive), Billy Joel-like Broadway-meets-chipping dancefloor material (Perfect Man) and delightful songs like the musically tricky Sometimes You Need where he sounds barely able to rouse himself, but beautifully.

Out of the Game -- a final and overt farewell to his dangerous days for the more rewarding life of domesticity and quiet sophistication -- was the album to come back for, although it hardly did serious damage to any charts outside of Britain and Denmark.

Perhaps after Garland, Lulu and the box set -- with all their attendant publicity and in some cases soul baring interviews -- there was Rufus fatigue.

But Wainwright, even when demanding, is always worth hearing . . . and Out of the Game is the album he is currently touring with a Dylan-like schedule.

post a comment