Graham Reid | | 12 min read

Steve Miller Band: Take the Money and Run

Steve Miller is a man who takes his time and gets things right: he is perhaps one of the most savvy musicians on the block (he held all his own publishing at a time when others were giving theirs away for a small bag of cash) and was within a whisker of finishing a university degree when he decided in the early Sixties to be a full time musician.

Did well at it too. His Greatest Hits packages (in various configurations over the years) have – as he admits – kept him and his band fed, watered and independent.

But if Miller's name is only familiar from those smooth Seventies FM hits like The Joker, Fly Like an Eagle, Abracadabra and so on which are staples of classic hits radio, it may surprise that 69-year old Miller – who also negotiated for himself very favourable recording contracts – can tell great stories. And stories of greats.

And the music he started with was at some distance from the style which made him famous. Yet with his two most recent albums Bingo! and Let Your Hair Down – blues covers – he's come back to the sound that made his name in the tough clubs of Chicago in the Sixties.

His lengthy catalogue has recently undergone reissue (which reminds just how clever, different and interesting those first five albums were when he worked with engineer Glyn Johns).

But let's start with those most recent blues albums, your first releases in 17 years.

But let's start with those most recent blues albums, your first releases in 17 years.

Well, now we are working on new stuff, but those albums were the result of me gathering all my music and CDs and digitising tthem.

Then I hit a button and punched 'blues' and 6000 songs came up, so I started going through them and got it down to a list of 1700, then 700, then 150 and then 40 I really wanted to play that would blend well with what we already play with our greatest hits like The Joker.

It turned out to be much bigger project than I thought, and much more fun.

I ended up working with Andy Johns who was a wonderful recording engineer who recorded all the Led Zeppelin hits.

He's really great drum engineer and guitar engineer

and likes to do guitar work. Next thing I knew I was roped in doing

guitar parts like it was 1968.

He's really great drum engineer and guitar engineer

and likes to do guitar work. Next thing I knew I was roped in doing

guitar parts like it was 1968.

It really completed that whole circle of the way I leraned to record. So we did two record and we've incorporated a lot of that into our shows over the last several years.

You've mentioned it so I want to ask you about 1968 because that was such a fascinating period for you and the band. I think the reissues have brought that home to people, just how different and innovative you were from the scene going on around you in San Francisco.

But before we talk about that, you grew up in Dallas and your dad knew Les Paul, T-Bone Walker and people like that? And you had a band and were working when you were 13?

Yeah. I was really fortunate because my parents loved music. My mother was a really great jazz singer and her brother was in the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. My dad loved jazz and blues and he had a tape recorder right after World War II, one of the first really good professional tape recorders. It was what all the radio stations used and he got his hands on one and started recording people when we lived in Milwaukee.

He offered to record Les Paul. Les and Mary Ford were working at a club in Milwaukee and they became very good friends with my family and the next thing you know there's all these parties going on at the house and Charles Mingus, Red Norvo, Tal Farlow, Les and Mary Ford are coming around and I'm hearing great music and meeting some really amazing people . . . and I'm just a little kid.

When I was five years old I understood that Les Paul was speeding tape up and slowing it down to make his instrument sound different, and that Mary was singing harmony with herself on the tape recorder. I also knew that if you wanted to put a single out you had to send postcards to all your friends so they could mail them in from different cities to different radio stations requesting your song. I got the whole picture right then, and it was 1949 or 1950.

I watched Les perform quite a bit and he was so good and funny and made it look so easy. He made anybody think they could play the guitar, he was so generous and sweet that way.

Next thing I knew we moved to Texas and I was nine years old and T-Bone Walker came over to the house to play a party. I had stayed home from school sick that day because my parent had rented a piano and I wanted to play it. T-Bone came over and played from 6pm to 5am and he and my dad became good friends. He came over again and again, so I have all these memories and he taught me how to play guitar behind my head and how to play single note leads. That was just amazing.

Then I started my own band and we were really good. We had a drummer who had been taking lessons since he was five so he was like child prodigy, he was like Gene Krupa and could play shuffles and anything. So when were 12 we started our band.

There were no rock'n'roll bands then because it was 1956. So I mimeographed a letter and sent it out to everybody saying we had a rock band – didn't say how old we were – but I had my band booked for the whole semester every Friday and Saturday, and we were making $75 a show. Boz Scaggs was in that band, not long after that up in college Ben Sidran was in the next one, so I always had a band going.

I never thought iId be able to make a living as a musician until I went to Chicago to go to university and Paul Butterfield had a record contract and I thought 'Wow, maybe I can do this'.

So I moved to Chicago, started playing in the neighbourhood of Muddy Waters. Howlin' Wolf, James Cotton and Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, AC Reed . . . a whole group of great musicians who were all grown men but their careers were all at a low point.

They'd had their hits, the blues had gone out of fashion and they were working these real Mafia nightclubs in Chicago. It was a real tough scene, the cops were on the take, the Mafia was on the take, the club business was tough.

We worked nine at night until four in the morning six days a week for $125. You couldn't put gas in your car and you'd stay at a friend's house. It was like that. But I got to play with Muddy and Howlin' Wolf and James Cotton. Buddy Guy and Junior Wells became good friends. I learned a lot of the Delta blues that had been turned into Chicago blues . . . which was kinda like what Texas blues was like. We played electric guitars and played harmonica through an amp. Hell, there were five good harmonica players in Dallas.

So I got serious and a couple of years later, after a few false starts, we ended up in San Francisco.

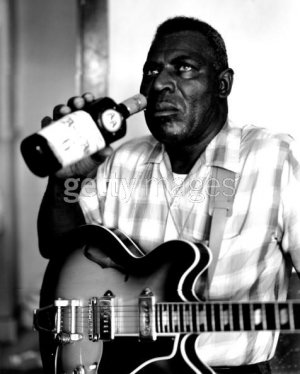

Before we talk about San Francisco I

want to ask, was it hard for a 21 year old white boy to sit in with

people like Howlin' Wolf? he'd be a formidable character (right), although I guess by that point you had

proved yourself on the bandstands?

Before we talk about San Francisco I

want to ask, was it hard for a 21 year old white boy to sit in with

people like Howlin' Wolf? he'd be a formidable character (right), although I guess by that point you had

proved yourself on the bandstands?

Let me tell you what these guys were like. The first time I went to see Howlin' Wolf I went with a friend of mine who weighed about 112 pounds and were going over to the west side of Chicago to Silvio's which was a really big club underneath the El.

It was a tough neighbourhood and when we walked in there was Howlin' Wolf's band on this wedding cake stage and they had on turquoise blue tuxedos and they were playing. But Howling Wolf wasn't in the room.

So I asked the bartender and he said, 'He's in the next room' and I opened this door and was standing right in the middle of Howlin' Wolf's stage where he was sitting in a chair playing harmonica. The band in the next room so they wouldn't be too loud. And there's Howlin' wolf playing to 400 people and we were there standing right there. So we slid to the back when his number was over and he said to the crowd – just a completely black country crowd in Chicago and we were kinda scared – and he said, 'I want you all to treat my little white friends real nice now'. And that's how our friendship started.

And Otis Rush? I'd go to a club and he'd be playing and he'd haul me up in the middle of a song and hand me his guitar and he'd just sing.

How did he know you could play, he'd seen you?

Oh yeah, because I had the band and here's the absurd part about it. I was 21 years old and I was competing for the same gigs as Muddy and Howlin' Wolf. There were five clubs where you could make a living and you sort of rotated. So you tried to bump into that rotation.

If you weren't playing on the near northside you were on the southside or on the west side or at Peppers. It was great training and boy was I glad to get out of there, they were seriously tough Chicago nightclubs.

But they respected you because you genuinely loved this music and could actually play it.

Yeah well, I grew up in Texas and Paul Butterfield had really broken the ground and his band of Sammy Lay, Jerome Arnold and Elvin Bishop – two black guys and two white guys. That was The Band for the Chicago blues scene for my money. They were like Little Walter's band, just great.

So that opened things up and it was a scene that was happening on the hip side of Chicago on the near northside with students and intellectuals and not too far from Rush Street, the Mafia strip. It was a groovy bohemian scene and we slipped over to the south side and they came over to the north side and band started integrating and we became good friends.

A lot of those guys came out to San Francisco after we went out, and Butterfield went out. When Bill Graham was running the Fillmore we were saying 'Get Muddy Waters, get James Cotton' and they would come out and their careers took off and they were playing colleges.

So what prompted you to go to San Francisco? I'd heard that Butterfield suggested you go?

The thing that was going on in San Francisco was it was no longer just a nightclub audience, they were playing in places that held like 1500 people. They had a much bigger scene and more bands and a lot was going on. So just from a musicians standpoint that was the place to go. It was a chance to make $1500 a night so from a business standpoint it was a hip scene, and it was the absolute epicentre of the psychedelic movement.

The Fillmore and the Family Dog were the hippest theatres in the county and they were running seven days a week. You could go see the Modern jazz Quartet, Johnny Cash, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy on a Wednesday night. So it was great melting pot and we were hearing about the scene as it was building when we were over in New York.

Butterfield had gone out and played the Fillmore and come back and told everybody how cool it was. And the Chicago scene was just a tough and ugly nightclub scene and nobody wanted to work that way.

People commentating on the time have

always said that your band was very different because live you would

play blues, but when you came to record Children of the Future you

went in another direction with electronics. You were consciously

different on record?

People commentating on the time have

always said that your band was very different because live you would

play blues, but when you came to record Children of the Future you

went in another direction with electronics. You were consciously

different on record?

I had been playing with tape recorders all my life and I couldn't wait to get into a studio and make records. When you are young you have all these ideas and you'd fiddled around pinging sounds between quarter-track machines and that stuff and you think if you only had $25000 you could go into a studio. To finally get into a studio was a big deal and I worked as a janitor in a studio to get studio time.

I had watched Les Paul make records and was absolutely intrigued by Bozo Goes to the Circus records when I was a kid which told stories but had lots of music. Then the Beatles pretty much were blazing a trail in front of everybody. And Simon and Garfunkel were making albums that were pieces, not just a quick collection of a hit and 11 fast tracks, as a lot of albums were.

So we worked hard on it and wanted to improve recording techniques and it was a very creative time in the studio, and the shows too because it just kept getting bigger and bigger. The Grateful Dead had something 1600 Mackintosh amps powering out. The heat alone was terrifying!

I remember seeing Paul Revere and the Raiders in an arena in Chicago with 1500 people and they were playing through two tiny theatre speakers . . . and that was considered a big deal.

So the light shows, stage shows and the sound systems were getting bigger and more inventive, and the same thing was going on the studio.

But you went to London to work with Gyn Johns at Olympic. I guess you read the small print on the back of British records and thought about him to produce your first album. But in England?

We investigated the situation in London and we talked to George Martin and he agreed to produce our record, but I didn't want to give him any [percentage] points! He wanted too much. So Glyn was an engineer and was available and he was great. We got got a very cool education on making records British style.

There was a very big difference I imagine.

Oh yeah, it was very cool and neat and organised. It was overdubs and parts and pieces and cutting tape. We did it all on four-track tape recorders, so we had to do a lot of experimental things. Olympic loved recording rock'n'roll and Capitol Records [in LA] had hated us because they were all right-wing people and thought we were communists or something. They didn't like us and the engineering staff walked out on me.

I thought I'd signed this contract and was going to get all these great resources but when I went down there all I got was politics. So we split and I had the right to produce my own record anywhere I wanted, which was one of the things I'd negotiated. And the rest is history. On and on it went.

The reissue of those first five albums

with those interesting liner notes show how very different your band

was from what was going. The electronics and the pop elements, for

example. But live you were still playing a lot of blues?

The reissue of those first five albums

with those interesting liner notes show how very different your band

was from what was going. The electronics and the pop elements, for

example. But live you were still playing a lot of blues?

We started as the Steve Miller Blues Band but we dropped the 'blues' because it identified us and stopped some people from listening to us. You got to remember it was quite a different time. Butterfield had gone to Europe as the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and they thought he played Dixieland.

We were writing a lot and when we got to San Francisco we'd just come from Chicago and we were playing my blues set, but I was writing more, and in the studio . . . and writing for the studio.

When the big commercial success came you would have enjoyed that, but that would have required of you to play the same songs night after night, which I don't imagine you did when playing blues sets which you could just mix up all the time.

The way it works now for us, we do about 60 cities a year and have done for the last many years except for a few breaks, and our audience really wants to hear The Joker and . . . There's about 14 songs they really want to hear. But that leaves nine or 10 pieces for the set, so whatever we're working on gets in. Sometimes it's acoustic stuff, sometimes it's jazz, sometimes blues. That brings it full circle. We started with Bongo! and Let Your Hair Down and we brought those in and got ourselves new material to play.

You took time away from recording; five years between Book of Dreams and Circle of Love, and an enormous gap after Wide River until Bingo!. Why?

The record business is a really tough

biz. You got to pay attention to it all the time. And they get in the

way and they screw up a lot of things. Sometimes they are good, but a

lot of times they are more trouble than they are worth, so we were

touring and fortunately for us our audience stayed with us and was

buying the Greatest Hits in great quantities, thank you very much. So

we didn't have to put records out. And the few times we did it was

always just like giving your baby to a bunch of gangsters.

The record business is a really tough

biz. You got to pay attention to it all the time. And they get in the

way and they screw up a lot of things. Sometimes they are good, but a

lot of times they are more trouble than they are worth, so we were

touring and fortunately for us our audience stayed with us and was

buying the Greatest Hits in great quantities, thank you very much. So

we didn't have to put records out. And the few times we did it was

always just like giving your baby to a bunch of gangsters.

The record business is much more fun now that it is smaller than when it was really big. Now that it's bad and no one knows what to do I'm in the studio all the time. I was there all day today.

Because you are in control of your career and you can say this is what we're going to put out and they are glad to have it?

No, it's not like that at all. It's because I have a good audience and we tour all the time and that keeps us financially able to pay for our own recording and can do whatever we want. Then we can talk to anybody we want about leasing it to them, or we can put it out ourselves. It's just a lot easier.

I've been negotiating a contract now for five months which should have been done in a day. I don't have time to to fool around with these clowns.

Other than that, I like the record business and we're having a lot of fun.

buck nelson - Mar 12, 2013

good for the soul you got it working thanks, Buck

SaveMike Pearson - Mar 12, 2013

I have Steve's Born 2B Blue album on Vinyl - an exceptional album. Totally different from his "joker" style stuff and obviously playing from the heart and inspiration of his growing up years. I shall have to get the Let you Hair down album. Great interview.

Savepost a comment