Graham Reid | | 12 min read

27 Coper Square: Marion Brown Quartet

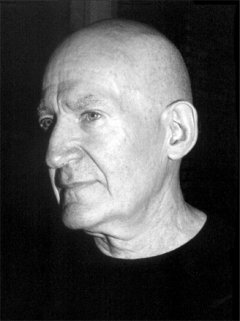

For a large part of his adult life, Bernard Stollman was just one of those New Yorkers in a suit going to work. He had an honorific title as an assistant attorney-general in New York City – “one of 600” – and an office on the 46th floor of the World Trade Center. As a lawyer, he represented the interests of patients in psychiatric facilities across the state.

“It was just a government job and I did that until I retired at 62. I'd previously got a job with the state of New York as a government lawyer at $17,000 a year, what they paid a beginning lawyer, and I was 50 years old. That wouldn't cover my expenses, it wasn't enough to survive on so I switched after two years [to this new position].

“I don't know how carefully they investigated my background,” he laughs.

“I said I was a lawyer for ESP but I never emphasised that part of my history, so I don't know how much they knew about me. The attorney general had just hired a lot of young lawyers and said, 'You're mature, you'll be a good counterbalance'.

“I had done almost no practice in law, but I didn't tell him that.”

What Stollman -- now 83 – had done was much more interesting than law.

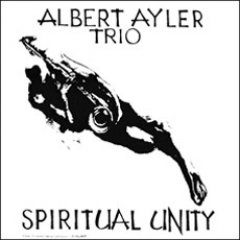

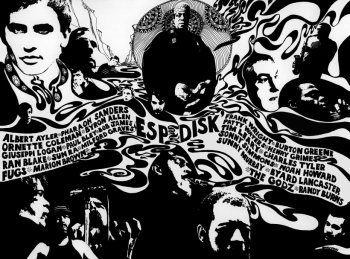

He had launched his own record label ESP-Disk in the mid Sixties and recorded and released records by many of the geniuses of modern music such as Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Pharoah Sanders and Sun Ra.

His label – never one to easily pigeonhole – also released albums by the socio-political poetry and satirical group The Fugs, an album by Charles Manson and the Family, the psychedelic alt-folk group Pearls Before Swine lead by their songwriter Tom Rapp, one-offs like the Marzette Watts album, the folk duo Holy Modal Rounders . . .

If you could describe the catalogue of ESP-Disk you'd simply say it was indescribable: “If you are going to be in the arts,” says Stollman, “you have to shake people up a little.”

The music on his label certainly did that – still does in fact – but Stollman came into the music business sideways and by accident. He admits when he started the label he really had no idea who many of the artists were or if they were any good, he just knew they moved him.

Speaking of Coleman and Ayler he says, “I was in awe of them both. I listened to them and was dumbfounded by them. I was the perfect listener because I had no preconceived prejudices, no previous history [with this new music].

“These things moved me. I had a broad but limited orientation to all art forms so I didn't look at the music as commerce . . . but I didn't have any reference other than my gut feelings. I wasn't concerned about whether anyone else would like it, [ESP-Disk] was the most supreme self-indulgence.

“I felt if it moves me it might move other people.”

Stollman had come to New York in '60 and worked with Florence Kennedy, a black woman with spina bifida whom he'd met at law school. She had an office on 5th and 8th and he became her go-fer. As important as the job were the parties she threw in her Harlem apartment and, he admits, her two beautiful sisters.

“But she had these two estates brought to her – the Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday estates – so without any real depth of knowledge at all about the music business I found myself working on these.

“They both died in the Fifties when I was otherwise engaged but Parker's widow and Billie's last husband were represented by Flo and in the brief period I was with her I started to research their music. Then I fled the office when I was tipped off there was a serious problem because the wife of Charlie Parker was not his last wife, and the thing was going to blow up. I didn't want to to be caught in the middle of it because I had been identified as associate counsel at a press conference.”

Stollman set up a little office on Broadway and over next few years in the early Sixties started to work for musicians (“they had no money but they were interesting”), initially with rock'n'rollers. With songwriters Otis Blackwell (many songs by Elvis) and Charlie Singleton (Strangers in the Night and many others) he formed publishing company.

“But there was a major problem though: their lives, their careers, their values and their behaviour. They had come through in the crossover between r'n'b and rock'n'roll and I wasn't remotely interested in r'n'b/rock'n'roll phenomenon and I wasn't about to get involved.

“I was 31 and I had missed that era just as I had missed the jazz era, but I started to represent what they called 'modern jazz musicians'.

“A young choreographer came to see me and said 'You help musicians, why aren't you helping Ornette and Cecil?' and I said, 'Ornette and Cecil who?'

She looked at me as if I had just exposed myself.

“She said, 'They are the princes of modern music and I have talked to them about you and they both want you to manage them'. I said I'd never managed anybody but I'd be really happy to talk with them, so give me their phone numbers. Suddenly I was introduced to the very top of the field, long before I had any idea of what was in the field.

“I worked with both of them and today I still represent Cecil's publishing company, almost 50 years later.”

The sole Coleman album that appeared on ESP-Disk was his Town Hall Concert 1962, a tape of which he brought to Stollman.

At the concert bassist David Izenson couldn't hear himself so turned up his monitor so on the tape the sound was distorted. Stollman took the tape to an engineer he knew who compressed it down. Stollman returned the tape to Coleman who, he says, tried to shop it to Blue Note but through legal complexities it ended up back with ESP-Disk and was one of the first on the label when it was launched in '65.

During this period Stollman also became aware of pianist Bud Powell – then living in France – and when Powell returned to New York with graphic designer Francis Paudras who recorded him (a relationship on which the film Round Midnight was based) he became his manager.

“He'd had enough of Paris and wanted to stay in New York, so I gave Paudras the airfare to go back to Paris and took a piece of art from him. Buttercup Powell, Bud's wife, had a master of Bud's sessions produced in Paris and she sold it to me and I put that record out, Bud Powell in Paris 1961.”

Stollman's great epiphany with this new music had come one afternoon at the Baby Grand in Harlem. On of Albert Ayler's friends from high school contacted Stollman and insisted he go and see the saxophonist playing on this particular Sunday.

“This was about Christmas/New Year and it was cold out but for some reason I walked the 30 or so blocks through the winter winds and snow. I walked in and sat down and a famous musicians trio was playing on the small elevated stage and they were excellent. There were maybe six or seven women in the audience with their coats on because the place was so cold and the barman was pretending to polish glasses.

“After five minutes, suddenly a young man brushed by me in a leather suit and had a big saxophone and he just jumped on the stage and started to play. He wasn't paying any attention to the band at all, he just crashed the performance and they stopped and looked –it was Elmo Hope and his trio – and Elmo closed the lid on his piano and the bass player stacked his bass and the drummer sat back and they listened to him.

“He played solo for about 20 or 30 minutes and it seemed like 10 seconds, it was so engrossing. I couldn't get over it. He hopped down from the stage covered in sweat and I went over to him and I said, 'Your work is beautiful, I'm starting a record label and I want you to be my first artist, would you do it?'

“He very gravely thought then said, 'I like that idea but I have to do a session at Atlantic Records in March and after that I will be available' and I thought to myself, 'You are starting a record company, are you?' and the second thought was 'Sure you'll remember me'. I didn't believe it for a minute. “Then in June the phone rang and it was Albert Ayler and he said, 'I'm ready to record'.

Stollman booked a small studio off Broadway which Mo Ashe of Folkways used (“it had to be cheap because he had no money”) and Ayler turned up with a trio of drummer Sunny Murray and bassist Gary Peacock, with Peacock's wife Annette.

Stollman says he and Annette sat on steps outside with the door open and listened to the session.

“I said, “Wow, what an auspicious beginning for a record label' and she nodded emphatically. After 27 minutes they finished playing. While it was underway the engineer left, I guess to take a leak, and left everything running.”

Stollman says many of these artists were easy to deal with (“I don't know if they read the agreement”) and Ayler particularly: “He was a doll and just kept recording for me, he had that freedom to do what he damn well pleased”.

As more artists gravitated to his label they brought fellow players, many of whom also recorded for ESP-Disk. But he was still learning who some of them were in this small community.

“In October '63 they had the October Revolution Festival at the defunct Cellar Cafe which was just a block away from my apartment, it was a strange and serendipitous thing.

“I hadn't met many of these people but there they were: Sun Ra, Marion Brown, Burton Greene, Paul Bley . . . all there.”

He approached Sun Ra and others to record (“they all said yes, they hadn't thought of a better idea, maybe they'd heard I'd recorded Albert but they never mentioned it”) and recalls Sun Ra's bass player Ronnie Boykins said he would also record for ESP-Disk but wanted to think about it: “Eight years later as the label was folding Ronnie said he was ready, so I think he was the last recording I did, the album was The Will Come, is Now,” he laughs.

Alongside these innovative musicians, ESP-Disk released albums by Pearls Before Swine, the Fugs, Timothy Leary and others far removed from these artists who are often referred to as jazz musicians, not a label Stollman likes.

“I was an enthusiast for the new, I called it free improvisation because I didn't like the word 'jazz' . . . and Duke Ellington hated it too, it was just a way of saying, 'These people are black'.

“The word was very imprecise, we didn't use it on the records in those early years, we called it free improvisation if we called it anything. We called it new music and that idea stuck.”

He says the musicians didn't need a lawyer, they needed a record label and he stepped into that role in the absence of anyone else doing it.

“There were a lot of people doing original things, something so important that people should hear it and I wanted to document it.”

He heard a tape from 18-year old college drop-out Tom Rapp (of Pearls Before Swine) who was living in Florida “and I cried, I was so moved by it”.He told Rapp to record some demos in a Florida studio and send him the tapes.

It arrived two weeks later and on the wrapping was written words like rubbish, garbage, no good and terrible.

“It turned out he'd gone to a born-again studio and these people were affronted by his music. I should have saved that paper.”

He invited Rapp and the Swine to New York where they camped out in his parents' lounge and had them record. They become one of the label's best sellers, but also the band that buckled the label.

“When we went out of business in '68, although not officially, we had three records in the pop charts. We were selling records like crazy, the Pearls and the Fugs. We couldn't keep up with the demand.

“But the year was '68 and the Pearls had a song by Tom Rapp called Uncle John which was an accusation that President Johnson was a war profiteer.

And the Fugs had a song called Kill for Peace.

“So between the two we got on the government's list – they had something going on then called Cointelpro, a counter intelligence programme, and the whole idea was to stamp out opposition to the war. I think they debated whether to have me killed, quietly and discreetly, or to put me out of business. I guess they decided to put me out of business and they did.

“They worked with the Pennsylvania Mob that had printing plant in Philadelphia that was printing our records . . . and they went on pressing our hit records on their own. They swamped the stores and our distributors got none. They were selling through one-stops, little stores that didn't care where they got records from and sold them for $1 – and the distributors were shut out of the process. So the phone suddenly stopped ringing and we were shut out of business while the plant was pressing records like crazy.

“We found out subsequently they sold at least a quarter of a million of each of these titles, they cleaned up on us. Kids being drafted bought them but we probably sold only 25,000 of each before we stopped cold.

“I was ship without a paddle or sail and I was too stupid to figure out then what had happened. So I let my staff go but kept the label open and added Charles Manson and a few other things, but it didn't natter because there was no business. For three years I just coasted going nowhere on my own.

“I was out of business but I didn't accept it.”

(It's worth also noting that other sources say musicians didn't get paid and there was some dissent in the ranks of those who had albums on ESP-Disk.)

In '74 he got married and shut down the

office and began licensing ESP-Disk to other labels, but after four

years had to go looking for work . . . and that lead to him dusting

off the legal background and putting on a suit.

In '74 he got married and shut down the

office and began licensing ESP-Disk to other labels, but after four

years had to go looking for work . . . and that lead to him dusting

off the legal background and putting on a suit.

And disappearing into the anonymous workforce until his retirement.

But neither Stollman's nor ESP-Disk's story ends there: he is still here – and so is the label.

After his divorce 22 years ago he says he floundered around and decided he would restart the label. When his parents died in '98 he'd received a small inheritance and so using that and living off the state pension he restarted ESP-Disk eight years ago.

He has a small staff working in an office in Brooklyn overseeing a substantial reissue programme, and a new deal with Naxos means this important 20th century music is getting out there once more. Aside from the digital platform they also do a small number of physically released CDs, seven titles in the past two months, another few this month, more in July.

And typically, Stollman is going to upset expectation. He has albums of rockabilly and comedy from tapes he has secured, one by the great Yma Sumac, more improvised music from the vaults . . .

“I just put it out to confound people.”

They lose money every year – not a lot, but Stollman doesn't have to pay tax because of it – but the albums are getting excellent press.

“There's no explanation for this. The bumblebee can't fly, it's wings won't permit it . . . but it flies anyway. There's no way this can work, but we're doing it.”

Today Bernard Stollman, 83, lives in Hudson, New York, "a charming small town with a unique history”.

“The main street has about 60 antique stores and very little else. There's a pharmacy, a coffee shop or two, a couple of law offices, the police station and city hall. That's it. But people flock here to buy antiques.

“I'm an antique here. But I am not for sale.”

For more information on ESP-Disk and its releases see here. In New Zealand Sarang Bang Records is the local agent for ESP-Disk, see here for links to that and other innovative and different music.

Footnote: Bernard Stollman died in April 2015

Graham - Jun 4, 2013

Great piece, some great music on ESP, many of them personal favourites. Cheers, Graham

Savepost a comment