Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Bob Dylan: Went to See the Gypsy

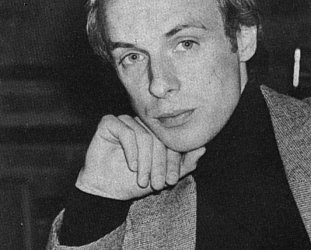

For most people, Bob Dylan arrived as fast as lightning and with the power of a hurricane.

Fifty years ago last week – fewer than 18 months after his largely ignored debut album – Bob Dylan was at Martin Luther King's famous March on Washington. King delivered his famous “I have a dream speech” and Dylan sang When the Ship Comes In (with Joan Baez) and a solo version of Only a Pawn in Their Game to around 300,000 gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall.

Just two years previous this cultural figurehead had been a little known folk singer in New York, mostly crashing on people's couches and singing in the style of his hero Woody Guthrie. Sometimes he'd change a few words on traditional songs and call them his own.

His self-titled debut album (1962) sold fewer than 3000 copies in the US at the time and then, almost overnight it seemed, he became the spokesman for a generation with songs like Blowin' in the Wind, the poetically apocalyptic A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall and the anthemic The Times They Are a-Changin'.

By the time he stood on the steps in Washington on that pivotal day in American history, his songs had been covered by dozens of artists and his fame was global.

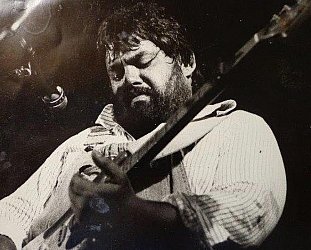

Then it really picked up speed as he plugged in his guitar for electric and electrifying rock (which alienated many folk fans) and his fame and influence just grew and grew. Not counting that debut, he'd delivered six groundbreaking albums in three years and one of them – Blonde on Blonde had been a double.

This kind of pace couldn't last and was emotionally punishing so -- using a motorcycle accident in '66 as a way out – he tried to retire to live a quieter life with his family. His music reflected that.

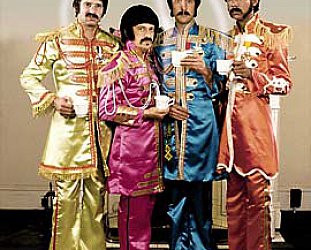

His albums John Wesley Harding ('67) and Nashville Skyline ('69) offered downbeat folk-flavoured and country-style songs at the time the world was going Techno-glow after the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's.

It was as if he was simultaneously exploring older highways while trying to deconstruct the legend which was attached to him. But people still scoured his lyrics for clues, Baez and others called him to rejoin the youth movement and give it direction, and freaks just kept turning up at his home in Woodstock.

So he released the myth demolishing

Self Portrait ('70), which contained some excellent songs

(Copper Kettle, Belle Isle) alongside ridiculous things like

his multi-tracked treatment of Paul Simon's The Boxer and MOR

ballads like Let It Be Me.

So he released the myth demolishing

Self Portrait ('70), which contained some excellent songs

(Copper Kettle, Belle Isle) alongside ridiculous things like

his multi-tracked treatment of Paul Simon's The Boxer and MOR

ballads like Let It Be Me.

As he said in the essay in the Biograph box set (85): “I wasn't going to be anybody's puppet and I figured this record would put an end to that ... I was just so fed up with all that who people thought I was nonsense."

Self Portrait, as he had hoped, was not well received. In his famous Rolling Stone review Greil Marcus opened with “What is this shit?”

The prevailing critical opinion – perhaps driven by, or depending on Marcus' review – would have you believe people hated this double album. But they didn't. It went to number four in the States and sold three million copies (it's a double, remember), and in this country – so much further from the expectations of American audiences perhaps – people carried it to parties and backyard barbecues.

It was easy listening Bob for people who just wanted to zone out. In my experience that was a lot of people. The damn thing was played everywhere. And enjoyed.

That Dylan's on-going Bootleg Series now turns it attention to that often derided period 1969-71 makes sense. If any years – which also included his understated New Morning released just four months after Self Portrait, and sessions with the Band which subsequently appeared as The Basement Tapes and on innumerable bootlegs – deserve a reconsideration it is these, which Dylan wrote about in his memoir Chronicles Vol 1 almost a decade ago.

He considered this period important enough to single out in a long career for Chronicles.

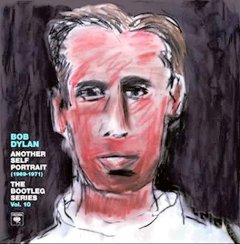

The double CD Another Self Portrait

(with another Dylan portraits as cover art, as unlike him today as the original cover was

like him then) offers stripped back versions of familiar songs (most

vast improvements by being more intimate), a dozen unreleased songs

(gentle treatments of traditional songs Pretty Saro and a

piano-supported Spanish is a Loving Tongue among them), two

excellent demos (Went to See the Gypsy, When I Paint My

Masterpiece), the unreleased Working on a Guru with George

Harrison, and a slow version of If Not For You with violin

(which Harrison covered on his All Things Must Pass album).

The double CD Another Self Portrait

(with another Dylan portraits as cover art, as unlike him today as the original cover was

like him then) offers stripped back versions of familiar songs (most

vast improvements by being more intimate), a dozen unreleased songs

(gentle treatments of traditional songs Pretty Saro and a

piano-supported Spanish is a Loving Tongue among them), two

excellent demos (Went to See the Gypsy, When I Paint My

Masterpiece), the unreleased Working on a Guru with George

Harrison, and a slow version of If Not For You with violin

(which Harrison covered on his All Things Must Pass album).

Many of these songs as with those on The Basement Tapes – be they original or traditional – seem to come from a time well before this. And even well before the time in which Dylan originally sang them, all those decades ago.

By their very simplicity and in Dylan's hands -- the explorer of future possibilities always, even now, going back and back for source material -- they reach into the tap roots of older American musics before they became commodified into Americana.

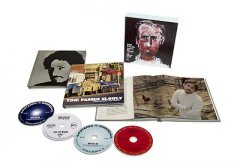

Another Self Portrait is a revisionist collection in a way, but it is the better for it – there's an expanded edition which includes

Dylan and the Band live at the Isle of Wight – and one of numerous

quiet delights which possess an easy familiarity.

Another Self Portrait is a revisionist collection in a way, but it is the better for it – there's an expanded edition which includes

Dylan and the Band live at the Isle of Wight – and one of numerous

quiet delights which possess an easy familiarity.

Oh, and Greil Marcus writes one of the liner essays.

He likes this one.

It's very, very hard not to. It's the sort of album people might once have take to parties and barbecues, if you get my drift.

For a more detailed review of Bob Dylan's Another Self Portrait see here.

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman - Sep 2, 2013

Re: The "Elvis" meeting and other mysteries to do with the Gypsy song, it's interesting how it finishes "in a little Minnesota town", isn't it?

SaveMy bet is he did indeed visit a fortune teller and it could have been in Hibbing. Just wove in a bunch of other stuff, and the Las Vegas reference just a bit of poetic licence. Cheers.

post a comment