Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Elvis Presley: Mr Songman (outtake)

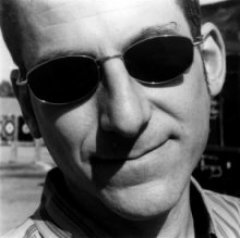

Memphis-born and based writer Robert Gordon knows the musical pulse of his city. He has documented it in books like It Came From Memphis and has written essays about Elvis Presley after being given access to private material in the Presley estate.

He has made documentary films, wrote the definitive biography of Muddy Waters (Can't Be Satisfied) and, among other things, produced an Al Green anthology box set (his liner notes were nominated for a Grammy).

His most recent project is an exceptional book Respect Yourself; Stax Records and the Soul Explosion which is nominally about the city's famous Stax Studio but is in fact is about so much more.

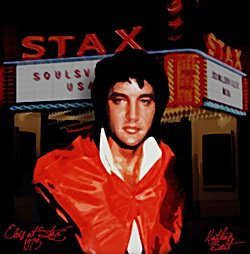

It embraces the racial divide in Memphis, the changes in the music business when corporates took control, the effect of the deaths of Otis Redding and especially Martin Luther King . . . and the business of Elvis Presley who, late in his career, did two lengthy sessions at Stax in July and December 1973.

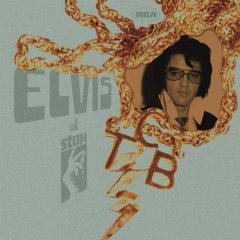

Gordon contributed the liner notes to the recent and fascinating three CD collection Elvis at Stax, and as always bring his insider knowledge and insight to these songs which might just have been Elvis' last great period in a recording studio.

We spoke to Gordon (right) about the remarkable and highly readable Respect Yourself (more on that at a later date) but also specifically about these sessions when Elvis seemed to be trying to reconnect to his music, and just where Elvis fitted in the whole Memphis story of music and race.

We spoke to Gordon (right) about the remarkable and highly readable Respect Yourself (more on that at a later date) but also specifically about these sessions when Elvis seemed to be trying to reconnect to his music, and just where Elvis fitted in the whole Memphis story of music and race.

We start with an interesting point Gordon makes in Respect Yourself, that money – serious money – only came into Memphis after Elvis died.

I guess you meant the opening of Graceland and Sun Studio tourism?

You know, that was a wake-up. For people here, until the day he died, was the laughing stock of the city. For one, he was associated with black music and that was to be denigrated at all times, as all black culture was.

When he died I was in 10th grade in 77 and it was a very divided city and we were still in the aftermath of bussing, so it was more than embers that were glowing. There were still fires being put out here and there.

Then Elvis dies and the city gets taken over by aliens. The only thing about these aliens is they were spending American greenbacks and so the city was like, 'Wait a minute, you mean there is money in that?”

When they saw the amount of money these people spent in the week of Elvis' death the city said 'Okay this Beale Street idea, let's pay attention, maybe there's money in it'. And now people are from a less racist time and are more open.

The division exists here but it is nothing like that was here in the Sixties.

I'm always curious about how black artists see Elvis. The older artists at Stax you spoke with who were around when he was breaking, what did they think of him? Or did they just not think of him at all?

I remember having a conversation with some of the older artists about when Elvis was breaking in the mid Fifties. “Gatemouth” Moore – the Reverend Bishop Dwight Arnold “Gatemouth” Moore – was a disc jockey and had been a huge blues singer in the Twenties and Thirties, and became a gospel singer thereafter. But he said, 'Elvis gave us a second career'.

That's what some people thought, but it's like you hear, some thought he was doing great things for African-Americans bringing a respect to that music even if . . .

I've read the newspaper articles of the time and the sense of fear and anger that Elvis instilled and the way he was despised was a real jolt, and it remains an amazing representation of America at the time.

At the same time the fact it was a white guy doing it made it different and I think a lot of people did get a new life.

Let's talk about Elvis at Stax, it was almost like the last hurrah in his career.

It was and the music gets shunted aside because it's a shadow of some of his even bigger hits. But if you were to somehow separate those recordings from everything that came before and played it for people they would go, 'Hey, that's great stuff. Who is that?' But when you say it's Elvis Presley they say, 'Oh, that's the guy who had all those other hits'.

He set a high bar in his career so these sessions tend to be overlooked in the comparison with the earlier groundbreaking music.

He seemed to be searching for the magic again? What I find interesting is the sessions were shapeless, just trying a few things, and not that sense of focus he had when he was at American Sound Studio [Chips Moman's studio in Memphis which has closed since Presley's superb sessions there in '69].

I agree and the summer sessions were much less focused than the winter ones. The divorce [from Priscilla] is weighing heavy here.

In June he is feeling like his world is crumbling. A Southern country boy and he's not sure, people weren't supposed to get divorced and it's tearing him up. In December he's survived that and has a new confidence.

But my sense is that at both sessions he is fishing around for songs. The difference between the two sessions truthfully is Chips Moman. He had the direction at American and the vision. Felton Jarvis at Stax and RCA was just trying to keep things from falling apart.

Up until 10 or 15 years I'd never thought of Elvis' music as autobiographical in any sense, yet the more I listen to the later period there are so many moving songs that take my breath away because they seems to personal. You Were Always on My Mind is extraordinary.

Up until 10 or 15 years I'd never thought of Elvis' music as autobiographical in any sense, yet the more I listen to the later period there are so many moving songs that take my breath away because they seems to personal. You Were Always on My Mind is extraordinary.

I agree with you. In these whole sessions, with one or two exceptions, there are dozens of songs, and almost every one can be applied to Elvis whether it's Mr Songman you think, 'Wow, here's the guy who is the monkey on the end of the organ grinder's leash and he's singing about that'.

Or he's singing about the distance he's feeling between himself and his child, he can't bear to have Priscilla leaving him, then there's a song about where he's happy with his girlfriend.

It's unified by Elvis sense of self in the songs.

Last time I spoke to you many years ago about an Elvis book you wrote I have never forgotten something you said. I'd always thought Dr Nick was the guy who was the villain in the Elvis story, but you said he was actually the one who protected Elvis, tried to moderate the pill intake and just keep him maintaining. You've now made me reconsider Colonel Tom Parker. The deal he did on the publishing gave Elvis Presley a freedom he might not otherwise have had.

Yeah, that's that's good, but let's not give the Colonel a total free pass here. (laughs)

No, he did the Elvis Presley wine.

The Colonel said no to Barbra Streisand for Elvis [to appear in the film] A Star is Born. My God, can you imagine if Elvis had been given a real dramatic role with Barbra Streisand? I love that story about Elvis going out to his first movie [audition] an he's memorised the whole script. If he had been given a real role at that time he would have thrown his all into it. The only reason he might have failed is he might have over-tried and not been able to contain his enthusiasm.

And that is was a man who had been deprived of enthusiasm for a long time.

But Colonel Parker's publishing deal did give Elvis room to move, if he'd wanted to move at that point?

Yes it allowed him that, and then on the other side did the Colonel not want him to make those moves? I think the Colonel had gambling debts.

There is much more about Elvis Presley's remarkable life and music at Elsewhere starting here. And this is just odd.

post a comment