Graham Reid | | 16 min read

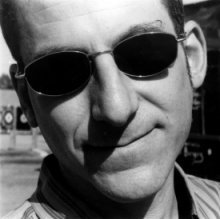

Memphis-born and based writer Robert Gordon knows the musical pulse of his city. He documented it in his book It Came From Memphis and has written essays about Elvis Presley after being given access to private material in the Presley estate.

He has made documentary films, wrote the definitive biography of Muddy Waters (Can't Be Satisfied) and, among other things, produced an Al Green anthology box set (his liner notes were nominated for a Grammy).

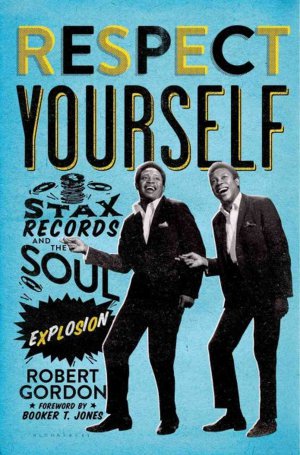

His most recent project is an exceptional book Respect Yourself; Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, which is nominally about the city's famous Stax Studio but is in fact is about so much more.

It embraces the racial divide in Memphis, the changes in the music business when corporates took control, the effect of the deaths of Otis Redding and especially Martin Luther King on the city and its people . . .

It is a rare biography of a music, a people and a city which changed the face of popular music and America.

Robert, congratulations of such a wonderful book, it is a brilliant balance of Stax and its music but also the character of Memphis the city, and of race and personalities. You must feel this was the book you were born to write given all that previous research you had done.

Yeah, when I was pitching the book I

was thinking this was the largest telling of the story I've done. I

told it with the hippies and the blues guys in It Came From Memphis

but here it is on a much larger scale. There are are whole different

set of complexities from the Seventies and the business world. So I

guess I did feel, not born to tell it so much, but based on what I

did as a teen it lead me to a very direct path to here.

Yeah, when I was pitching the book I

was thinking this was the largest telling of the story I've done. I

told it with the hippies and the blues guys in It Came From Memphis

but here it is on a much larger scale. There are are whole different

set of complexities from the Seventies and the business world. So I

guess I did feel, not born to tell it so much, but based on what I

did as a teen it lead me to a very direct path to here.

You mentioned in an earlier discussion with me that you've already had some pre-publication reviews and I'm curious about that. I guess you or your publisher sent the manuscript out to well-known music writers and critics?

There's a publicity machine and this case a fairly small one that is associated with the publisher that gets these out. Everyone sends to the major trade magazines like BookList, Kirkus and Publisher Weekly, those three specifically – where I had been reviewed before but had never gotten a starred review -- and each gave me a starred review. And I've got to say it was confirmation that, 'Wow, this book must be good'.

What about fellow writers? We who write about music work in a small world and you know your friends and enemies. Do people ring-fence areas of expertise? Whether it be Elvis Presley or Jimi Hendrix. Is that how it is? Or are people very helpful even though they might be working in similar research areas.

I think everyone's different. Everything I've done has been because people have cooperated with me and wanted to tell their stories so I always try to cooperate. I could give you a list of people who have contacted me and I've delivered to them hours of transcribed interviews. That's the way I feel, but other people feel, 'This is my territory, keep off it'. They are less friendly.

That's the difference between a historian who wants the information out there regardless of who is accessing it or writing it, and the territorial people.

In the blues world people are very territorial, but there's nothing appealing about that because no one could get anything done.

I've had the misfortune of interviewing some elderly blues gentlemen who are so tight-lipped you wonder why you are wasting your time. Or they are full of cliches. But you have great access to people and I imagine many of these people you would have known before you started to write this book. Is that a problem in that you have a personal relationship but now you have to probe them for facts and perhaps areas of discomfort for them?

Hey, are we doing the interview because I'm loving this?

We are, and I am great believer in not interpreting what someone says, so you say what you want and I will publish a full transcription. So it is your voice not mine.

Oh, okay. Sure sure. So you were asking?

That difficulty of establishing a relationship then putting on another hat, the interviewer as it were.

Yeeeeh. There is that, that is one way to look at it. The other way though is to say there is a conflict you have between people you have a friendship with and then you want to write anything critical. And most people are big enough to hear it because you want to be as deep and honest and forthright as you can be with a book. So there is that conflict sometimes.

The other is though is, I live in the town with some of these people and that colours to some extent what I'm going to say because I'm gonna go to the supermarket and bump into them. But at the same time this is a story that happened a long time ago and most people these days understand what they think happened is true to them and what other people happened, even when it is conflict with their own ideas, believe that is the truth too.

But some people don't (laughs)

Before we start specifically talking about some of these characters, I want to talk about race. What impresses me about the book is the way you deal with a city divided back in the Sixties. These people were enormously courageous in a sense in what they did, but were they aware of that in crossing racial lines?

Absolutely not. For the most part. There wasn't this sense of courage, it was a shared sensibility of music and I think more for the African-American people than the whites it was unusual. I don't want to downplay how unusual it was but for Duck Dunn to go down there versus for Booker T to walk in and get treated respectfully, but that's the rarer incident. The African-American experience of getting respect was more rare.

I think for the MG guys, the Mar-Keys guys, just the fact they were getting to play black music they loved in clubs was the thrill. Doing it as a mixed thing was great, but no one felt they were Freedom Riders or part of the Civil Rights movement. It was very close.

Keep in mind it wasn't until '67 when they go to Europe that they realise how big this thing had become. They were still very city-limits orientated. They are hitting the road some and seeing something in America because the sales are telling them that. But it really comes in Europe.

There are some remarkable characters who are very articulate but Al Bell [originally the label's PR man who became president then later took over Motown Records] stands out as an almost visionary character. Am I reading to much into that?

Absolutely not. Al is a giant of a man, physically imposing, authoritative in speech, inspiring, with a sense of possibility that dwarf's the common person's notions of what can be. So with the power of a rising record company behind him he was able to take them to places and the vision was solid, the accounting was not.

His vision was better than his pocketbook.

I imagine if he had moved into the political sphere his name would be known on the international platform as a great civil right figure.

I believe so. If things had not sunk I believe in a way – well beyond the way Berry Gordy is perceived as an entrepreneurial pioneer – I believe Al would have been much deeper into the socio-cultural fabric.

I love the fact Estelle Axton is such a key figure because she had that almost in-house r'n'D that she managed to do. These were people who really had their finger on the pulse in many ways, I suspect.

Yeaaaah. You know, but . . .

Have I overstated that?

When you say finger on the pulse what do you mean?

That she knew what music might work, what artists might, because she was so shop-front as it were.

Right. That is totally true but here's the thing. Since I published It Came From Memphis and I would travel out of town and people were always amazed that this happened here. I always wonder, these were people who were not afraid to go across the tracks as it were, to racially mix, to buck the trend. But it must have happened in other towns too and there are examples I guess . . .

Part of me wants to believe there is a magic in Memphis and we see the proof of that in the 20s, 30s and 40s with the blues guys, and in the 50s with the Sun Studio guys, then in the 60s and 70s with the Stax guys.

You can look at the 20th century and say, not only did magic happen there but it lingered through decades.

Then part of me wants to say, 'Nah it's that people were open to the magic'. Magic happens everywhere, so something in a society that is so closed and racist as this one was for so long, people who are looking to not participate in that are pushed to the edges. And it is the edges where the changes can occur.

There is that wonderful quote in the book, and I can't remember who said it: 'Memphis is a town where nothing ever happens and the impossible always does'.

Yeah, it's something a guy said in It Came From Memphis and I just thought it would be such a perfect description of the city I had to re-use it.

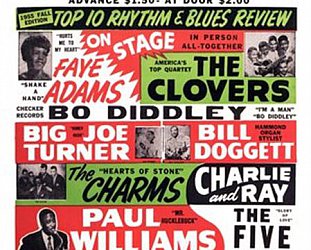

It's such a great line which encapsulates the dichotomy. I want to ask you about when things changed but let me say this: I'm 62 now so I remember a period in the 60s when something similar happened all the world and that was records/hits were broken by DJ by DJ, city by city. And DJs would flip a record over and find a song. I was amazed to read what I thought were big hits were actually originally B-sides. That sense of discovery seemed like a magical period in American popular music and there was no pattern to it.

In part it's because the technology hadn't become corporatised and you see that in the changes in Stax in that second period, the Gulf and Western years and that sense of conglomorisation.

Don't forget the step in between that freedom of DJ Dewey Phillips and a few years after with Al Bell's early years, versus the playlist sent down from corporate headquarters in the sky. There is that period where [Stax enforcer and thug] Johnny Baylor comes in and where hits are broken because arms are broken. It's not so much discovery as mandate.

It's interesting. We shouldn't romanticise it too much because it turned ugly pretty quick.

Things changed remarkably rapidly with Otis's death, the Atlantic deal and then Martin Luther King's death. You would have been a bit young to remember all of that, but were you old enough to recall household conversations about what the killing of Dr King meant.

Yes. I remember learning the word 'curfew' after Dr King was assassinated. I was probably seven and I remember my father taking me downtown and opening the window on the 12th floor over Main Street and showing us the sanitation marchers going by in silence. I remember the manager of the bowling alley using the 'n' word loud and freely. So I remember the whole sense of the racism that pervaded here.

I cry sometimes when I see my children playing with mixed races and international kids just gamboling about. And just getting to hold the door open for an African-American is like, 'What these people have seen'.

The presumption Robert, from the kind of work you do, is that you perhaps came from a liberal family. But sometimes that's not the case. What was your family like?

My dad was a lawyer and my mum was a speech therapist so they weren't hippies or anything, but they bought some tie-dye jeans.

We all made that mistake.

(laughs) Yeah. I don't remember this, but my parent told me about it and I sort of rang bells. After Dr King was assassinated there was a black lawyer in town and my dad did't know him well, perhaps by name, but he invited that lawyer and his wife to dinner so that one-on-one they could begin to mend society. I don't recall that incident but it seems ingrained in me and is in my core.

You are right, we see kids playing together in way that would have been unknown to their grandparent's generation, and we forget how quickly the world did change. In 30 years an enormous part of our Western societies changed.

It gives you hope and although the world now don't look so friendly it gives that hope things can change.

What is Memphis like as a city today, is it still divided along certain lines in places.

Absolutely. Oh yeah

Yes, that's been my experience too.

There is a surface . . . Downtown is deeply integrated. People mix, but people still live apart mostly. The business world is the inverse of what it was racially but living is divided still. But what I see of my kids in school -- they are now in 9th and 11th grades -- and man, they don't know which was further ago, unfortunately, the Civil Rights movement or World War I. In a way that's great, but in a way it's scary because they need to know how recently these things were . But they will get that as they get older.

You made an interesting point about Memphis in the book and it never really occurred to me: that money came into Memphis after Elvis died. I guess you meant the opening of Graceland and Sun Studio tourism.

You know, that was a wake-up. For people here, until the day he died, Elvis was the laughing stock of the city. For one he was associated with black music and that was to be denigrated at all times as all black culture was. When he died I was in 10th grade in 77 and it was a very divided city and we were still in the aftermath of bussing, so it was more than embers that were glowing. There were still fires being put out here and there.

Then Elvis dies and the city gets taken over by aliens. The only thing about these aliens is they spending American greenbacks and so the city was like, 'Wait a minute, you mean there is money in that?'

When they saw the amount of money these people spent in the week of Elvis' death the city said 'Okay, this Beale Street idea? Let's pay attention, maybe there's money in it'. And now people are from less racist time and are more open.

The division exists here but it is nothing like that was here in the Sixties.

I'm always curious about how black artists see Elvis. I know what Chuck D of Pubic Enemy said [in Fight the Power: “Elvis was a hero to most but he never meant shit to me, straight up racist that mother was”] But the older artists at Stax you spoke with who were around when he was breaking, what did they think of him? Or did they just not think of him at all.

I remember having a conversation with some of the older artists about when Elvis was breaking in the mid 50s, “Gatemouth” Moore – the Reverend Bishop Dwight Arnold “Gatemouth” Moore – was a [radio] disc jockey and had been a huge blues singer in the 20s and 30s and became a gospel singer thereafter. But he said, 'Elvis gave us a second career'.

That's what some people thought, but it's like you hear, some thought he was doing great things for African-Americans bringing a respect to that music even if . . .

I've read the newspaper articles of the time and the sense of fear and anger that Elvis instilled and the way he was despised is a real jolt, and it raises an amazing representation of America at the time.

At the same time the fact it was a white guy doing it made it different and I think a lot of people did get a new life.

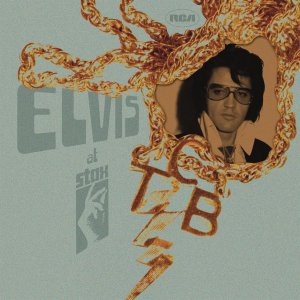

Let's talk about Elvis at Stax, it was almost like the last hurrah in his career.

It was, and the music gets shunted

aside because it's a shadow of some of his even bigger hits. But if

you were to somehow separate those recordings from everything that

came before and played it for people they would go, 'Hey, that's

great stuff. Who is that?' But when you say it's Elvis Presley they

say, 'Oh, that's the guy who had all those other hits'.

It was, and the music gets shunted

aside because it's a shadow of some of his even bigger hits. But if

you were to somehow separate those recordings from everything that

came before and played it for people they would go, 'Hey, that's

great stuff. Who is that?' But when you say it's Elvis Presley they

say, 'Oh, that's the guy who had all those other hits'.

He set a high bar in his career so these sessions tend to be overlooked in the comparison with the earlier groundbreaking music.

He seemed to be searching for the magic again? What I find interesting is the sessions were shapeless, just trying a few things, and not that sense of focus he had when he was at American Sound Studio [Chips Moman's studio in Memphis which has closed since Presley's superb sessions there in '69].

I agree and the summer sessions were much less focused than the winter ones. The divorce [from Priscilla] is weighing heavy here.

In June he is feeling like his world is crumbling. A Southern country boy and he's not sure, people weren't supposed to get divorced and it's tearing him up. In December he's survived that and has a new confidence.

But my sense is that at both sessions he is fishing around for songs. The difference between the two sessions truthfully is Chips Moman. He had the direction at American and the vision. Felton Jarvis at Stax and RCA was just trying to keep things from falling apart.

Up until 10 or 15 years I'd never thought of Elvis' music as autobiographical in any sense, yet the more I listen to the later period there are so many moving songs that take my breath away because they seems to personal. You Were Always on My Mind is extraordinary.

I agree with you. In these whole sessions, with one or two exceptions, there are dozens of songs, and almost every one can be applied to Elvis whether it's Mr Songman you think, 'Wow, here's the guy who is the monkey on the end of the organ grinder's leash and he's singing about that'.

Or he's singing about the distance he's feeling between himself and his child, he can't bear to have Priscilla leaving him, then there's a song about where he's happy with his girlfriend.

It's unified by Elvis sense of self in the songs.

Last time I spoke to you many years ago about an Elvis book you wrote I have never forgotten something you said. I'd always thought Dr Nick was the guy who was the villain in the Elvis story, but you said he was actually the one who protected Elvis, tried to moderate the pill intake and just keep him maintaining. You've now made me reconsider Colonel Tom Parker. The deal he did on the publishing gave Elvis Presley a freedom he might not otherwise have had.

Yeah, that's that's good, but let's not give the Colonel a total free pass here. (laughs)

No, he did the Elvis Presley wine.

The Colonel said no to Barbra Streisand for Elvis [to appear in the film] A Star is Born. My God, can you imagine if Elvis had been given a real dramatic role with Barbra Streisand? I love that story about Elvis going out to his first movie [audition] an he's memorised the whole script. If he had been given a real role at that time he would have thrown his all into it. The only reason he might have failed is he might have over-tried and not been able to contain his enthusiasm.

And that is was a man who had been deprived of enthusiasm for a long time.

But Colonel Parker's publishing deal did give Elvis room to move, if he'd wanted to move at that point?

Yes it allowed him that, and then on the other side did the Colonel not want him to make those moves? I think the Colonel had gambling debts.

We know Graceland and Sun are multimillion dollar businesses these days, but is that happening with Stax in that it is reclaiming its place, not just in Memphis history but in the history of American music?

My sense of that is so out of proportion I can't answer (laughs). I'm the guy whose been immersed in Stax for the past five years so it's like, “What do you mean it's not important?' I think Motown will always be more preeminent because it was much more massively successful.

I thought that Motown documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown was not only a great eye-opener about the band but it got into race at Motown, and you never hear much about that.

Where Motown is more successful, the history at Stax tells more about America. Motown is an economic success story and Berry Gordy was fighting the odds and is a groundbreaking African-American entrepreneur, Joe Lewis-like in what he fought and what he achieved.

But the Stax story, with the neighbourhood and people like Al [Bell] and [founder] Jim [Stewart]' . . there is so much humanity, and inhumanity.

And Jim never expected Stax to be a black music label, that was not his intention.

Man, when I heard the song Blue Roses or any of the early [Stewart pre-Stax label] Satellite stuff that Jim produced you just can't believe how sappy it is. It is soggy milquetoast.

But this is the guy.

Yeah, this is the guy. It's a beautiful story of the flowering of a human being and it's incredible. And Jim is the unlikeliest guy, he is very retiring, shies from publicity – even sent his granddaughter to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to accept his award – because he doesn't like it.

But you have to understand that too. His life was a roller-coaster and you can understand he would say, 'I'm done with that fairground'. That party was over.

One last question. You put a full-stop on a book and then publishers do what they do, and you might have a yawning chasm of time. Are you working on anything new right now?

I usually juggle several large projects but the book did become all consuming for more months than I expected, six or eight months, so I've left some short film projects I'm trying to finish.

You can go to msbluestrail.org/films and see some of these short films I'v been making for the state of Mississippi. I'm finishing up a round of those and hoping to get them done by the end of the year. But I may not.

I've had this documentary I've been trying to raise money for the last four years and in fact I really got serious on this book when the big grant I thought we'd get [for that] didn't come through. I though I'd better do that book I've been promising, better go dig out that mouldering contract. (laughs)

And the film?

It is about Gore Vidal and William Buckley having a series of 10 debates [in 1968] at the Republican and Democratic conventions.

I've seen some clips on You Tube, quite extraordinary.

Extraordinary. Two beautiful, towering, eloquent figures who hate each other and set off on high falutin' thoughts and are immediately on the low road. We're slowly moving on that and I'll find out in November whether I'll get this other grant. If I do that''ll be the next big thing.

I don't have any new book ideas, go an idea?

Has anyone done a definitive and truth telling book on BB King?

I tell you, I've got a friend who wrote the all text for the BB King museum and I kept telling him 'Write this book because if it ain't you it's Charles Sawyer from '72 or BB himself which is going to be somewhat suspect'. I don't know, it's a good idea but I think there's someone better qualified than me.

I dunno, your Muddy Waters book was damn impressive. Last question: I had a feeling you had a falling out with the Presley estate. Or is that gossip, rumour and innuendo?

I guess it's gossip, rumour and innuendo. I hadn't heard that. I don't g to their cocktail parties but that's because they don't drink my brand of scotch.

They have asked for changes in work I've done for them and I've made the changes.

If you work for someone that's their prerogative I guess.

Exactly.

Mike Rudge - Jan 2, 2014

Great interview graham. Just over halfway through the book at the moment. Captures the energy, politics and social context of the time so well. The story from family business to a "business family" to a corporate monster is like watching a train wreck coming. But throughout it there is the music, morphing along with and reflecting the business and an increasingly strident black American voice.

SaveGreat we have people like Robert Gordon to document it so well.

post a comment