Graham Reid | | 14 min read

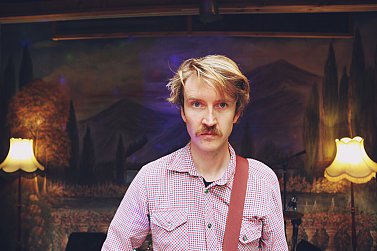

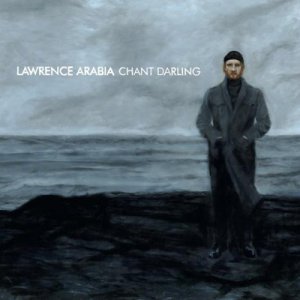

Lawrence Arabia: The Bisexual

Lawrence Arabia – known at home as James Milne – has made some of the most interesting New Zealand music of the past decade. Over three albums he has crafted fascinating pop which is embellished by strings and strange sounds, but always highly melodic and lyrically engrossing..

His has been an interesting career from playing stand-in bassist for Okkervil River in Australia before on his own albums, also helming his band the Reduction Agents, being in the Brunettes, making various guest appearances, living and playing and recording in London, touring in the States . . .

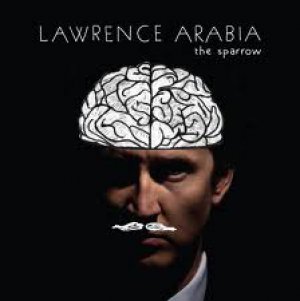

He won the inaugural Taite Music Award for his album Chant Darling, has written soundtrack music, counts among his friends and peers Liam and Elroy Finn, won a New Zealand Music Award for best male artist for his most recent album The Sparrow . . .

He's currently recording a new album – culling abut 25 demos written over the past year down to something coherent – and is father to a one-year old.

He's a cricket follower and enthusiastic user of Twitter where he engages with the arts, politics and cricket as much as music: “Twitter is my preferred communication, I have 4500 followers. It's a time waster but I enjoy it.”

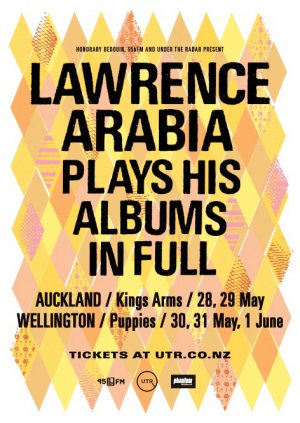

He can also be disarmingly candid in

conversation (as you will see) and soon is going to be playing each

of his three albums live in their entirety.

He can also be disarmingly candid in

conversation (as you will see) and soon is going to be playing each

of his three albums live in their entirety.

Not a new idea he admits, as he has a coffee in a cafe near his Auckland home, and one he has also done previously when he presented his third album The Sparrow at the Auckland Town Hall in July 2012.

So what prompted you at this point to want to do this?

I'm always looking to do something different with my shows and I've been occasionally suggesting to the Phoenix Foundation that they should do it, make a short season of their albums. But they scoffed at me saying, 'Do you know how much work that would be?'. So I said I would do it, I've got fewer albums . . .

But they are sometimes musically complex.

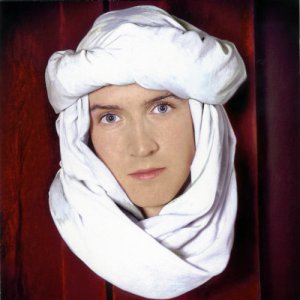

Yes, but less complex to represent live I'd say. The first one [Lawrence Arabia, 2006] is very complex and is odd and idiosyncratic. It's the most difficult and I think I've played all the songs on it at some point, but some of them not terribly successfully.

So you've had to listen to all your albums again. Most musicians never do that, or they tell me they don't.

Especially coming up to a new album you take stock and maybe some people should listen to their old albums because a lot of people let their audiences down. They make these records and claim defiantly they are the best they've ever made. Yet everyone who listens to them begs to differ.

Noel Gallagher was like that. Every

Oasis album was the best they'd ever done, then six months later he'd

say it was rubbish. When you listen to that first album now, what do

you think about it?

Noel Gallagher was like that. Every

Oasis album was the best they'd ever done, then six months later he'd

say it was rubbish. When you listen to that first album now, what do

you think about it?

I was surprised when I heard it again. There were lots of influences that I liked, in a very amateurish way there was some Bowie-ish stuff which I kind of enjoyed, and maybe moments of drama that I've ever been able to recapture.

I didn't feel I was an unorthodox songwriter at the time, but listening back some of the songs are quite odd.

More and more I'm listening to people who are making more and more complex music. Like Liam Finn's new album, and Grayson Gilmour's.

Yes. It feels like people have been engaging with a lot of complex music, either compositionally or texturally,. In a lot of modern r'n'b there are a lot of cut-up beats and quite intense sounds, and even jangly indie music has got layers and layers of reverb and fuzz. And there's compositionally complex stuff like Dirty Projectors.

But in life there has been a return to simplicity, people are having chickens in the backyard. Maybe music does need a few chickens in the backyard at the moment.

I've been listening to Mac De Marco's record [Salad Days] and he's really fashionable and Pitchfork love him, but it's actually quite simple and most redolent of the Kinks and Jonathan Richman, heartfelt youthful and slightly melancholy pop songs.

You are going to be revisiting songs

you haven't played for a long time.

You are going to be revisiting songs

you haven't played for a long time.

Yeah, some I might have played once on a first tour to promote the record, and then never attempted them again. The only complex thing about The Sparrow is the string parts, but the scores are all there and we've done it before so we do know how to do it.

The biggest task is going through the session files for the first album and pulling off samples and loading them and trying to mimic sounds.

How many people on stage then?

For the first two albums we'll have five on stage. A rock band set-up, but I have one other instrumentalist who plays keyboards so we can add extra sounds onto it. And a string quartet for The Sparrow.

What I liked about the Town Hall show was it was a kind of formal setting, that was great. It had a sense of occasion, your music requires that. But this time it's the Kings Arms? You know what that's like. Six rows from the front people are talking and 10 rows back everyone's just drinking and chatting. Was there not another venue?

Not one that I could make money at. It was amazing doing the Town Hall and it was like, 'We could do this all the time!' But the reality is I'm a parent and I can't indulge myself and I have to be a lot more pragmatic about things.

Our audience is normally respectful and I'm not expecting there to be 500 people in the Kings Arms. It's a bit for the fans really and I'm making an effort to promote it.

Hopefully it's full enough that everyone's got a good view but I don't think it will be packed to the gunnels. There are not many venues where you can sell 300 tickets a night and make money. Places like the Q Theatre you pay $1000 a night to hire so your margins are slim. It's nice to make money and support my family.

As everyone knows, 'touring is how musicians make their money now'. Apparently. [laughs]

You'll sell CDs on the night and

that'll help. Did you make any money off the Chant Darling album, for

example?

You'll sell CDs on the night and

that'll help. Did you make any money off the Chant Darling album, for

example?

Yeah. If I actually itemised the cost of recording over two years I probably didn't, but what I spent on the recording was minimal. I was still using the equipment I used for the previous record and I did it all at home save one day at The Lab where we mixed it. It sold quite well, maybe 3000 in New Zealand including digital. That's reasonably good in this day and age.

And The Sparrow?

It's probably sold half that.

No sudden blip in sales when it won you a

Tui [New Zealand Music Awards]?

No blip in sales. I think the thing about the Tuis is if you become a mega-winner it does, but just winning one award doesn't.

And you had to race off and play that night?

Yeah, because I hadn't thought about booking a show around the Tuis, I didn't even know I was nominated at the point I was thinking of shows.

You made some comment about how you

used to laugh about the Tuis?

Yeah, that was during my speech. I said when we were recording the [Sparrow] record with Connan [Mockasin] and Elroy, Liam's brother, we were watching because Liam was nominated. And we wanted to watch the red carpet. But it seemed, and still seems, absurd to me. I couldn't let the irony of being up there go unnoted. It felt awkward to me. For most people in the music industry this is not a reflection of their life, all the celebrities and corporate hosts. This is a veneer which doesn't exist in most people's lives.

I've always enjoys anyone who punches through that. HomeBrew did it.

I wasn't trying to make some grand statement and I was also honoured and it was great. But I had to say something about it.

Your first album was 2006, you've been

a fulltime musicians since then?

Your first album was 2006, you've been

a fulltime musicians since then?

Yeah, when we moved to London I worked in a bookstore and a shop for homesick New Zealanders for a while.

And you toured with Okkervil River?

Yeah, once in Australia at the end of 2005. They ended up appearing on my bio when I was trying to make a name for myself, I needed to mention someone who was credible. You have to build up your resume somehow.

And you are recording a new album.

Yes, I've been demoing for about a year. I've got a year-old daughter and I started writing around the same time as [she was born].

But I'm working with Mike Fabulous

[left in picture, of the Black Seeds] and leaving a lot of the arrangements up to him. People

use producers and let them have a bit of autonomy but I've always

been a bit of a control freak. But I like what he does. His own music

sounds nothing like mine but when we came together for the the

Fabulous/Arabia record [of 2011] I think it was sympathetic.

But I'm working with Mike Fabulous

[left in picture, of the Black Seeds] and leaving a lot of the arrangements up to him. People

use producers and let them have a bit of autonomy but I've always

been a bit of a control freak. But I like what he does. His own music

sounds nothing like mine but when we came together for the the

Fabulous/Arabia record [of 2011] I think it was sympathetic.

Where do you see yourself in the scheme of things in New Zealand music?

When I put that first record out I thought I was a young weird person, but I can feel myself slowly slipping along a spectrum which takes me much closer to Don McGlashan and Dave Dobbyn.

It is directly proportional to age.

But there's nothing to stop an older person from making a weird and challenging record. Liam has a thing on his website and it says, 'veteran up-and-comer'. I like that. He always feels – and I see this too – when you are trying to make it overseas you are answering questions you'd be asked if you were just a new artist. He's still answering those questions even though he's been releasing records for 15 years. I empathise that.

Every time I release records in the States and Europe, especially the States, I am being asked 'Why are you called Lawrence Arabia? Where does the name come from?'

You have a very sound profile in New Zealand though. People are very interested in these shows.

Yes, it's amazing.

Why would you be surprised by that?

Because I still feel like the same person who was trying to make things happen. That's born from some insecurity. It's the same thing you feel with parents, you inevitably feel like a child stuck at a certain age. I feel more comfortable now, but when I'm releasing something or trying to promote a tour I feel the same insecurity that I had when I first started which was, 'Is anyone going to care, why would anyone care?'

Do you think, 'Will they like this?' or is that less important than 'Why would they care?' ?

I do ask 'Will they like it?' and asking that question at least poses a challenge to yourself in that it forces you to make something of an effort, rather than, 'Whatever I do they are going to lap it up'.

You think this new album is going to be any significant departure, or an incremental growth on what you've done so far?

Every record has been some kind of departure, so if this record is different it wouldn't be a departure. If anything, making the same record would be the departure because it wasn't unexpected. I've always been quite nostalgic and revisiting old record in inherently nostalgic and part of me would like to make a record a bit like the first two, and the music I've been writing is more concise pop songs really.

When you say nostalgic, how do you

mean?

When you say nostalgic, how do you

mean?

I've always had a sadness about a period of time that has disappeared, whether it be the end of a holiday or something in the past. I really enjoyed 5th form but 6th form was hateful. So I have this fear of the now. I think back to mini golden ages in my life that can't be recaptured. But it goes beyond that to harking back to the late Seventies in New York.

Nostalgia about your own life can lead to sentimentality but I don't get that from your music.

No, it isn't sentimental, is it? On The Sparrow I had this idea in my had about a novel about me when I was 20 . . . One of the times I'm particularly nostalgic for is around that age when the world is opening up and the song Travelling Shoes is about being in Christchurch at that time. I'm always writing songs about being in Christchurch at that moment. But I don't think they are sentimental because that time wasn't particularly pleasant for me.

It's confusing because it is quite nostalgic but the reality of my life at that time was quite unhappy, so it is more nostalgic for the frustration, confounding and artistically challenging.

But you are nostalgic for something you never knew, like New York in the Seventies? How does that work for you?

It makes it more difficult to celebrate the present. If I look back to some of the last decade there have been certain moments in New Zealand which people will become quite nostalgic about, the sense of community which existed. Some people are able to appreciate it in the moment but it often takes some years to put it in a historical context.

It happens when people change and move in different directions and look back at that moment when they were together. In the Seventies in New York there was a flux and flow of like-minded people feeding off each other. In a sense you have that too though. Think of the people you've mentioned in the course of this conversation.

Yeah, but they are in New York and Europe and I'm in Auckland with a young family [laughs]. That's great, but it does pose nostalgic questions.

Is it limiting to be here?

I found it difficult being overseas actually because it felt like you were questioning every artistic decision as a career decision, whereas in New Zealand you can approach any artistic decisions in a different way. There is more space and a luxury to do that. That's freeing.

Doing it because you love it is a freedom because you aren't going to sell 30,000 copies of an album, you can't aim for a market like that. So you can get on and do what you do.

Yes, it is a career for me but that's a good way to approach it.

People help you do things here, there's

a supportive community which doesn't have its hand out for money

first.

People help you do things here, there's

a supportive community which doesn't have its hand out for money

first.

Yes. There are all these flow charts which ask whether you should work for free and the answer is always, 'No'. I disagree with that. The culture of professionalism is just creeping capitalism into an area which should be righteous and communal. Increasingly [the arts] is being infiltrated by less righteous ideals.

Music is transcendent. I'm not saying there aren't people making righteous crazy music, but in the absence of record labels there have been a lot more enticements to work with corporates and they are sponsored by brands to do things. It is really prevalent in the States, like Beck did that Sound And Vision thing with 300 musicians. But it was an ad for some phone company or something.

It's sad that it requires corporations to make those things happen in a token way, making [corporate] people feel just a little bit less guilty about their rapacious attitudes and what they do to the world. Like massive oil companies sponsoring artistic events. Philanthropists sponsor opera while they are plundering Third World countries, but it doesn't balance the scale.

Are you an optimist?

Yeah. If I look back there was an almost megalomaniacal streak for while. I was really driven when my first record came out and when we moved to England. I was constantly e-mailing people and setting up tours and promoting shows in London and getting a residency. And that's stuff I would find daunting now. A lot of that networking by the internet was still in its infancy but I was always trying to connect with people I admired and wanted to work with, because I thought, 'I have a place in the world and I want to make it happen'.

And these days you are more focused with your energy?

Yeah, but I feel a bit more scared about doing that now. It feels odd writing an e-mail to someone asking to do something. I feel maybe more realistic, or insecure, about my position. I look back and some of it was a bit forceful and some things really paid off at the time.

In that past decade was a special highpoint where you were really happy?

There was a time when I was living in London and I was really unhappy about the way I was recording Chant Darling, because I kept discarding things and I couldn't make the record I wanted to make. But through that and persistent e-mailing there was a time between late 2007 and mid 2008 when it seemed like stuff was getting interesting and I was getting traction.

I got that tour with Feist and got a

feature in the Sunday Times about this new wave of New Zealand bands.

There was my photo in the Sunday Times magazine.

I got that tour with Feist and got a

feature in the Sunday Times about this new wave of New Zealand bands.

There was my photo in the Sunday Times magazine.

So that arrogant, forceful e-mailing I'd been doing had actually worked. We played a show in Paris with Feist and one of the A&R people from XL Records came to see us and we went out for lunch and I was thinking, 'This is actually happening'.

Unfortunately it wasn't quite the big bang for my career.

Why didn't it happen then?

When I toured The Sparrow and not much was happening -- I didn't have a booking agent in the States, nothing could click – and it made me think I just don't have what it takes to transcend to another level.

Personally or in the music?

Personally almost. The sheer force of charisma and personality. It's that thing, 'What's Father John Misty got that I don't have?' It's some degree of personal charisma in myself as this half-Scottish, Protestant self-deprecating New Zealander. I don't have what he does as someone from LA. It's a different thing. It's a bit more subtle [what I have] and doesn't necessarily work.

But given the situation I'm in now I have got record deals overseas and the opportunity to release records. So am I optimistic? I do feel optimistic and pleased with having any audience overseas and feel optimistic that my next record will connect better than the previous ones.

It's actually useful to take stock at this point too.

It's amazing also how being in your 30s – and having a child – the questions you start asking yourself. You become a person you wouldn't have thought you'd become 10 years before.

When you were 22 do you think you would have recognised yourself as you are now?

[laughs] I would have hoped I wouldn't have had some of these thoughts. I wanted to be bohemian all the time, I wanted to be able to transcend the expectations of the world. I didn't expect it, but my dream would have been that I'd be more successful now.

But my realistic hope was that I was never going to be this successful . . . so I've actually done better than I thought I would do when I was 22.

.

post a comment