Graham Reid | | 5 min read

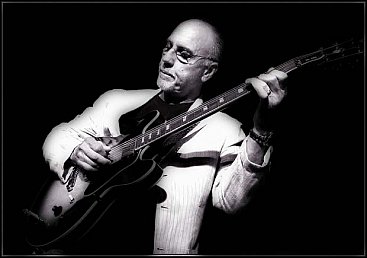

Larry Carlton --- four time Grammy winner and during the 60s and 70s one of the most in-demand session guitarists on Los Angeles for a roll-call of rock, pop and jazz stars – recalls one especially hopeless session in 74.

It came when John Lennon – then on an 18 month “lost weekend” break from Yoko Ono – ended up on a booze'n'coke binge in Los Angles and, with Phil Spector, tried to record an album of rock'n'roll standards. Among dozens of others, Carlton got the call from Spector.

“I came in excited that it was John Lennon,” says Carlton, who at that time had just finished work on Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark album, “but he didn't show up for three hours.

“Me and Leon Russell and a number of other people were just hanging around and finally they said 'Okay let's start' and we did Bony Moronie, that old song from the Sixties which of course I know.

“John was so drunk he was calling the chord changes to me like “A, I gotta girl named Bony Moronie, D dah-dah . . .” And I said, “I got it!” It was a drag.

“I drove Leon back to his hotel that evening and I said, 'Man, that was just such a drag” and Leon, in that Southern accent of his said, 'You ain't kiddin'. Ahm back to Tulsa in the mornin'.

“I got home and called Phil Spector's office, it was about midnight, and said, 'This is Larry and I'm not going to be able to make the rest of the week'. It wasn't fun.”

Carlton's career in studios saw him contribute the guitar solo to Steely Dan's Kid Charlemagne (considered by Rolling Stone magazine to be one of the three best in rock), record with everyone from Sammy Davis Jnr to Dolly Parton, play on dozens of television themes and soundtracks (that was his guitar on the Grammy-winning theme to Hill Street Blues) and also run a parallel career as a producer and player with the jazz group the Crusaders.

Since the late 70s he's had a high-profile career under his own name as a jazz guitarist, but recalls his first paying studio job which launched his career of more than 3000 sessions.

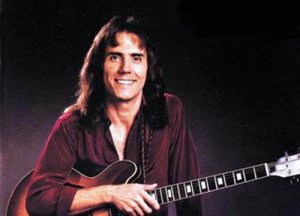

“I was about 18 and there was a local producer I'd met. He was the drummer in the surf band the Challengers and they'd had a minor hit. He was going in the studio to do a new album of cover instrumentals and he called me because, I assume, I could read music well but I still sounded young.

“So I went in and there were the big boys: Hal Blaine, Joe Osborn, Larry Knechtel . . .” he says, naming key players in the formidable Wrecking Crew musicians who anonymously played on songs by the Beach Boys, Monkees and dozens of others. “I don't think I knew who they were and came out of there and told people I'd played with so-and-so. I was surprised, and I was probably nervous.”

Because he could read music and, as a jazz musician, was a quick study in the studio he just kept being called back. People like Mitchell and Steely Dan were easy to work with because they would just leave space for him to fill.

“Joni can play Joni Mitchell guitar music with her tunings, but she has great ears so wanted to be around players and she enjoyed what they played. We didn't work very hard on her records, it was all just very natural.”

He recalls trying to play George

Harrison's Here Comes the Sun for someone's album as especially hard

as he'd never heard the song, but Michael Jackson's She's Out of My

Life was easy.

He recalls trying to play George

Harrison's Here Comes the Sun for someone's album as especially hard

as he'd never heard the song, but Michael Jackson's She's Out of My

Life was easy.

“I met a number of the artists for sure but there was a percentage of dates where it was just the music and the artist wasn't there. When I recorded She's Out of My Life for Michael Jackson, he wasn't there. I was honoured though because I wasn't doing session work at the time but [producer] Quincy Jones, whom I knew, wanted me on it.”

Curiously, given the years he put in, session work was not a career which appealed to him.

“I'd seen those session guys when I was doing that surf music album and they were pale, cigarette hanging out of their mouths and they looked really beat up. I left that session thinking I didn't ever want to do that. I just wanted to play jazz in a smoky nightclub.

“So I did have an ambition, but it didn't come about for a long time. Jazz musicians didn't make money, but back in the day if you were part of what we'll call the A team [as a session player] you could make a very nice living and not travel.”

His career as a jazz musician also came about by accident. He'd cut back on session work and had his own studio where he was making a decent living as a producer-cum-player.

“So I was transitioning out of doing nine hours a day in the studio to the next level, and I was playing Dante's, a jazz club in North Hollywood. The band was myself, Jeff Porcaro [session drummer, later of Toto], Joe Sample and Pops Popwell [both Crusaders] and we played every Tuesday night for a while.

“One night an executive from CBS Records was there and afterwards said, 'Ever thought about making a record?' And that's how it came about. At that point I was just enjoying playing. I had quit taking session work somewhat and was just playing my guitar away from the studio. I was brought up to be a player, so it felt good to be stretching out again.

“Because I was playing real well because I was enjoying the new enthusiasm. I just followed along. It was a great ride.”

And still is. At 66 he tours as much as he wants, is in demand for workshops and various ventures, and helms his own jazz quartet (the group playing with him here however are Australians hand-picked by his Gold Coast-based friend Louie Shelton, a former LA session guitarist who produced Seals and Croft). Recently he played his Kid Charlemagne solo live with Steely Dan for the first time when invited to tour with them.

“It really was fun. Their guitarist John Herington is their musical director he knew all of my parts from the record so the only homework I had to do was I learned the solo note-for-note from Kid Charlemagne.

“That was the first time I'd ever learned one of my solos and played it verbatim. I assumed, correctly, the audience was expecting to see that solo done by me because they never had before. “John had all the stuff covered so I could just coast.”

Living in Nashville these past 17

years, Larry Carlton is one of the most acclaimed jazz guitarists of

his generation and was a session man without parallel when he chose

to be. But he wears each accolade lightly and with humour.

Living in Nashville these past 17

years, Larry Carlton is one of the most acclaimed jazz guitarists of

his generation and was a session man without parallel when he chose

to be. But he wears each accolade lightly and with humour.

“Because of when I was born I got to digest each style – rock'n'roll, surf music, rock and jazz – as it came up. So if someone wanted a certain thing I was most likely familiar with it.”

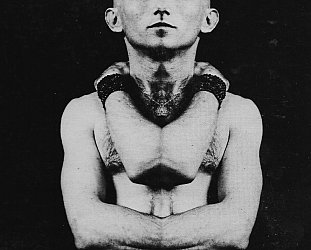

He's also a survivor. In 88 he was wounded in throat in a random shooting outside his studio, it happened five years after he became a Christian.

“A number of Christian musicians, when they found out I'd had [a religious] experience and that I was committed, asked if I was going to start playing some Christian songs.

“I said, 'No, God hasn't told me to do anything like that',” he laughs. “I was still allowed to play jazz.”

post a comment