Graham Reid | | 14 min read

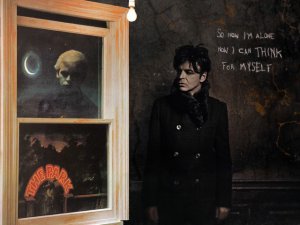

Gary Numan: Lost

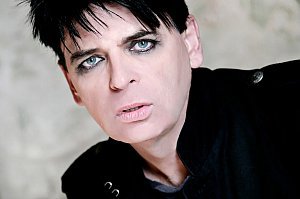

About 15 minutes into a very casual and chatty conversation with Gary Numan -- during which he's talked about his three kids, a prolonged bout of depression, almost breaking up with his wife and then how they'd undergone IVF treatment and lost the baby and being choked with emotion on stage – I interrupt and say, “Many people would be surprised to hear you talk like this Gary, because they think of you as some weird android from the late Seventies. But there is a beating heart inside that machine”.

He laughs, not for the first or last time in the conversation, because he is very aware of the perception out there.

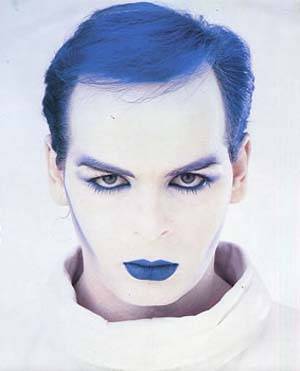

Here's the stoney-faced man who sprang to fame with emotionally detached songs like Are Friends Electric? and Cars back in the late Seventies and early Eighties, whose persona on stage was that of some strangely distant robotic misanthrope.

It served him well, but briefly.

It served him well, but briefly.

He was furiously productive – four albums in just over three years – but in America he was a one-hit wonder and back home in Britain his star fell after a series of albums of variable returns.

He continued to write and perform but time moved on . . . then curiously moved back towards him. A little over a decade ago the likes of Trent Reznor (Nine Inch Nails) and others started saying how innovative Numan had been, how important he was and there were numerous covers of his songs.

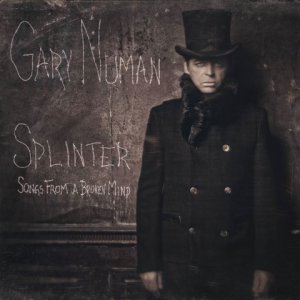

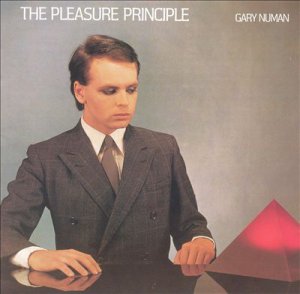

But in the past 10 years Numan has been off the radar. He did a 30th anniversary tour in 2010 when he played the whole of his Pleasure Principle album in its entirety, but his new album Splinter; Songs from a Broken Mind – a heavy dark and often bruisingly emotion encounter, with the exception of the heart-stopping ballad Lost – is his first album in seven years.

A lot happened in that time, not the

least that depression, the near-separation, his wife Gemma suffering

post-natal depression and more. Including finally leaving Britain to

live in Los Angeles which had been on the agenda for years.

A lot happened in that time, not the

least that depression, the near-separation, his wife Gemma suffering

post-natal depression and more. Including finally leaving Britain to

live in Los Angeles which had been on the agenda for years.

And that's where our phone call catches him in advance of his Auckland concert at the Studio on May 23.

He is happy, thoughtful, without guile and disarmingly honest. But if you look back at interviews in his heyday he always was, speaking about his nervousness, uncertainties and passions with rare candor. He is one of the nicest men it has been Elsewhere's pleasure to speak with, and so here is the complete transcript of our conversation. We leave all the stuff about the kids included even though its not very rock'n'roll because they are important in locating the man in his emotional space.

I'm talking to you in Los Angeles, that's you new home now?

Yeah, been here for about a year and half now

And you are enjoying that?

Oh, God yeah!

All that good weather hasn't got to you yet?

(laughs) God, I absolutely love it, we're very very happy here. I moved here with my wife and three children and it's a big thing to do. I lived in England for 54 years so to up the whole family is a big commitment. I was absolutely sure it was the right thing to do but you never really know for sure until you get there, and we wondered whether the children would take to it or not.

And have the kids have fitted in okay?

Yeah, the funny thing about the

children is they were so adaptable to it, they just settled straight

in from day one with no problems. I couldn't believe how easy it was.

Luckily in England they went to a Steiner school and they got into

one here, so the similarities between the schools is absolute: they

look the same, they smell the same, the materials are the same . . .

and the schools are very multicultural. My children were among the

few actual English people in their school in England and here again

they are one of the few English people, so to them its completely

normal and they are very happy.

Yeah, the funny thing about the

children is they were so adaptable to it, they just settled straight

in from day one with no problems. I couldn't believe how easy it was.

Luckily in England they went to a Steiner school and they got into

one here, so the similarities between the schools is absolute: they

look the same, they smell the same, the materials are the same . . .

and the schools are very multicultural. My children were among the

few actual English people in their school in England and here again

they are one of the few English people, so to them its completely

normal and they are very happy.

At the school there are mountains around and palm trees, its sunny and gentle. Where we live we have a swimming pool and the kids are in heaven with that.

I would be too. That sounds wonderful. I guess you ask yourself, 'What took me so long?'

That's exactly what I've said.

Was it work that took you there, because you do soundtracks and LA is soundtrack city. Was that some part of the reason for going?

It was a part of it. I'd like to develop the film score side of what I do more. I wanted to concentrate on North America for quite some time because I've never really done it properly in terms of my album and touring career. My wife has wanted to live in America pretty much since the day she was born, so there was that gentle but relentless pressure to move here. (laughs)

We've been together 22 years and I don't think a day has gone by that she hasn't mentioned America in some way or another, right up until the day we moved. So she's very happy.

So she won that argument . . . eventually?

(laughs) Oh yeah, every one of them actually. But it's the weather and a very different lifestyle compared with Britain, and British weather seems to be getting worse if anything. And also the friendliness.

We came here a lot over the past few years and people are so friendly and accommodating which, no disrespect to Britain, but it's not like that there. Here you drive out to the shops and even that is a friendly, happy experience. I love it.

Is this going to mean your next album is going to be clappy, happy and sunshine-infused?

(laughs) I'm absolutely sure it isn't. When I came here I'd recorded about half of this Splinter album, I'd done the first half in Britain. So I finished it off here and it's impossible to tell which were done in Los Angeles and which were done back in England.

So it seems the environment doesn't have much of a part to play in what I do. That part of me, the creative part, comes from a certain part of my bran and is triggered by certain things and the environment doesn't seem to be one of them.

So I'm fairly certain I'm not going to be writing Shiny Happy People or anything like that.

I imagine you write by yourself then go

into a studio and close the door so it doesn't matter what the world

outside looks like because you aren't going to see it.

I imagine you write by yourself then go

into a studio and close the door so it doesn't matter what the world

outside looks like because you aren't going to see it.

That's it, the way I see it. I go into a studio and close the door and start to imagine. You let things out that bother you or whatever your process is, it doesn't matter.

The studio I've built here I purposely built it with a window that doesn't look outside. I don't want to be sitting in my studio looking out at a sunny climate and beautiful weather. I want to be shut in this little dark box so I can imagine all the things I need to imagine, and so far it's worked really well. I finished the album here, I'm just finishing a film score I've been working on, I've done a song that was end credits for a film a few months back . . . so I've done a fair amount of work since I've been here. It's very easy to work here.

The music is as dark as anything I've ever done before, so there's no problem with that.

Let's talk about Splinter in a minute

then. I find it a remarkable album for a number of reasons, but you

talked before about the work you do. It always struck me that you

were the guy who went to work. You were enormously prolific at the

end of the Seventies and start of the Eighties, I think four albums

in a little over three years. You were disciplined.

Let's talk about Splinter in a minute

then. I find it a remarkable album for a number of reasons, but you

talked before about the work you do. It always struck me that you

were the guy who went to work. You were enormously prolific at the

end of the Seventies and start of the Eighties, I think four albums

in a little over three years. You were disciplined.

I certainly was until the early to mid Nineties when it started to slow down a bit. The music became a bit heavier and much darker. I got married and started to think about family and my first child came along in 2003.

I'd started to slow down, previously there was an album every two years, then it was four and even then I thought that was way too big a gap. I was fully intending to change that.

I did an album in 2006/07 called Jagged and the one before that had been years before, and I thought that gap was ridiculous. So I fully intended to have another album out within a couple of years, but unfortunately I was diagnosed with depression and I didn't write a song at all for about maybe three or four years. Nothing.

The cure they give you for depression makes you not care about anything. It takes away the depression which is fantastic but replaces it with a couldn't-care- less attitude. Unfortunately that also meant I didn't write anything because I couldn't care less now. (laughs)

People were saying to me, 'Your career is crumbling, you're not doing anything, you're playing gigs but you're not playing any new song and people are losing interest'. I just didn't care because of the tablets.

So it took me a while to realise and come off them and get back to reality, and when I did that I started to write properly again. I made an album called Sun Rising as a side project. But by the time Splinter came out [in late 2013] it was seven years between that and Jagged, which is just ridiculous and that will absolutely not happen again.

I'd like to put out an album at least every two years.

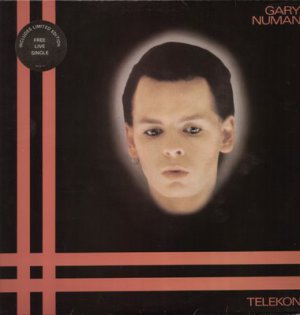

You've been very candid about things.

Some people have said you were emotionally detached or whatever, but

I've often heard autobiographical things in your music, like Remind

Me to Smile on Telekon. That's a fantastic sentiment. You've been

candid about the difficulties you and your wife went through in the

past few years, and this album really has been born of pain and anger

and sadness and confusion.

You've been very candid about things.

Some people have said you were emotionally detached or whatever, but

I've often heard autobiographical things in your music, like Remind

Me to Smile on Telekon. That's a fantastic sentiment. You've been

candid about the difficulties you and your wife went through in the

past few years, and this album really has been born of pain and anger

and sadness and confusion.

It has, to be honest. Obviously the depression is the fundamental package that it sits in, but beyond that it caused many other problems. There's a song on the album called Lost for example.

Yes, Lost is a very beautiful and emotionally naked song.

I wrote that round about the time I was thinking of leaving the marriage because we were getting on so badly. When you start to have problems in a relationship you tend to focus on the most recent argument and you get very narrow in your thinking and emotions, and your reaction to things.

I went out that morning and started to write down that particular song. I wanted to write down what it would be like if she wasn't there, and I was almost doing it in a spiteful way to begin with. But the more I started to write the more I realised how amazing she was and what I would be giving up, and I fell in love with her all over again.

It sounds very corny I'm afraid, but that's what happened in the space of that one morning and afternoon. I realised I'd been an absolute idiot and it was the depression and all the stuff that was going on, and writing that [song] really helped fix our problems and we sorted things out very quickly after that. There are other songs on there related to it.

There are songs there that are not to do with the depression, like I am Dust and We're the Unforgiven. I'm trying to write my first epic novel at the moment and those are ideas from that. It's not all depression but even the novel is fairly heavy, so they fitted and belonged there.

It's probably the most emotionally charged album I've ever made and came from a very difficult period.

I know such things can be cathartic for

writers, is that how you look back on it, that it got things out of

your system?

I know such things can be cathartic for

writers, is that how you look back on it, that it got things out of

your system?

Massively. I've go no skills in psychiatry but my opinion is that by being able to write helps you . . . as I started to get better and being able to write again at all I honestly believed it helped me to understand it and come to terms with it. You can liken it to someone who would go and speak to a therapist. Essentially you are talking out your problems to someone who is listening and can give you a bit of guidance. When you write a song in a way you are a doing a similar thing. You want it to be accurate so you write it down and if it doesn't say what you want it to say you think about it again and try to find the right words.

In doing that you are talking to yourself and just getting the stuff out. I found that massively helpful to me.

I think now I am arguably a slightly calmer and better person than I was when I got the depression.

How does that translate when you perform those songs live? Does that take you back into that place or do you simply become the performer as a separate person.

For most of them I am now a performer, although I still find Lost very difficult if I'm truthful. I have to be very careful when I do that. A while ago I was doing it and my wife was with me, she's with me all the time when I tour, and I saw her at one point and I lost it completely. It was really embarrassing. With that one in particular I have to be very careful to not think what it's about, I have to think of the words as if i'm reading them in a book and not attach myself to the sentiment behind it.

There's another song actually called a Prayer for the Unborn from a few albums ago and that's a memory of when my wife and I were trying to have children. We had to go IVF because we couldn't have children naturally, to begin with anyway. The first IVF experience we had she got pregnant and it was very successful. But then there was something wrong with the baby and it died. It was all very horrible. And I wrote that song about that. It took me years and years to sing that without getting upset.

So there are some songs that do bring back deeply felt things and they are difficult to do sometimes.

Many people would be surprised to hear you talk like this Gary, because they think of you as some weird android from the late Seventies, but there is a beating heart inside that machine.

(laughs) Oh yes.

In that regard, a friend of mine said

he saw you in 1980 and again in 2011 and he wanted me to ask about

that time gap . Is it difficult striking a balance between the old

and the new material to satisfy an audience, because I know you've

spoken about being trapped by that past and the Pleasure Principle

period. Is a set list increasingly difficult or do you know you just

have to do some songs?

In that regard, a friend of mine said

he saw you in 1980 and again in 2011 and he wanted me to ask about

that time gap . Is it difficult striking a balance between the old

and the new material to satisfy an audience, because I know you've

spoken about being trapped by that past and the Pleasure Principle

period. Is a set list increasingly difficult or do you know you just

have to do some songs?

There are some songs you think you've got to do because if you don't people will get grumpy and upset. I struggled with that for quite a long time, but after a while I just stopped being overly bothered about it, I play the songs that I like.

I recognise the obligation that people pay money, but it is my show that they are coming to see and it has to be something I like. If you just did songs that other people want to hear and you are perhaps no longer interested in you are in effect turning art into a job, and I don't think it should be like that. Nevertheless there is the understanding that these people have paid to come and see you and have put an effort to be there, so it is a difficult line to find.

Now on this tour I'm doing more old songs than I've ever done before – it's about 50/50 – but of the old songs they are songs able to be muscled up so they sound comfortable alongside the new stuff which is heavy and dark. So the song are the same and people will recognise them, but they are just bigger and heavier versions of those song.

So it makes for set which is quite hard work, an hour and 40 or whatever. Except for Lost which is a three minute breathing space in the middle. Apart from that it is absolutely full on. It's exciting because of that and it does seem to be a really good balance. I'm convinced I've got the balance absolutely right.

You did The Pleasure Principle in its entirety a few years ago. Did you enjoy doing that in that there were songs you wouldn't have played for a long time and you rediscovered?

It's not my favourite thing to do and I'm not a retro-oriented person at all. I hate nostalgia in music and have always been quite vocal about not doing it in the past, but these old album shows are very few and far between,. It's one of those things where you recognise there are people out there who love all that stuff and usually don't get to hear it very often because I don't normally play it, so they were a nod of appreciation to that generation of fans.

I have to say though that when I did that Pleasure Principle tour I was dreading it. I didn't want to do it at all. But it was actually alright and it wasn't quite the horrible experience I thought it would be, and I thought the songs sounded quite interesting. It was first time I'd played some of them since I'd made them in '79. I just thought they were quirky and odd bits of music and I was almost proud of it in a way.

Gary, I'm going to get a hurry up. I asked some people what they would want to ask you and one person asked about cover versions. There have a been a lot of covers of your song and I notice the new extended edition of Grace Jones' Nightclubbing album has a previously unreleased version of her doing Me, I Disconnect From You. Have you heard any really great covers of your music?

Several actually. My favourite would be the Nine Inch Nails version of Metal, that was amazing and brilliant. Pop Will Eat Itself did a version of a song called Friends and that was genus. Foo Fighters did Down in the Park which was great as well. But there have been so many.

And I have to ask, an outstandingly bad one?

(laughs) Yeah, there's been quite a few of them as well in my opinion. But no, I would never want humiliate anybody like that. I am genuinely flattered and proud whenever anybody does it. Whether I like the version or not, I think it's a very lovely thing for somebody to do and it's a pat on my back. So it would be horrible of me to ridicule anybody for doing it. But yes, to be honest there have been quite a few corkingly bad ones.

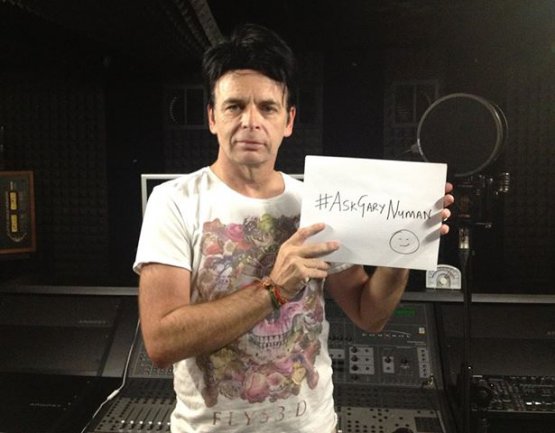

And finally. You have 30 seconds to answer this Gary. How do you see the future of recorded music in this internet age. Your time starts . . . now.

I think its a very positive thing. For all of the downside with downloading and that, it is balanced out by giving us other media like Twitter and Facebook which have made it possible for an individual and an independent band like myself to reach out to fans in a way we couldn't do before. So where it takes on the one hand it gives back on the other.

I think it's very exciting time to be a musician.

post a comment