Graham Reid | | 14 min read

The album arrives with that accumulated cachet of Floyd's long career from those Syd Barrett days, through Dark Side of the Moon, bassist-songwriter Roger Waters' helming them to The Wall, then guitarist David Gilmour taking control for the past three decades after Waters' departure.

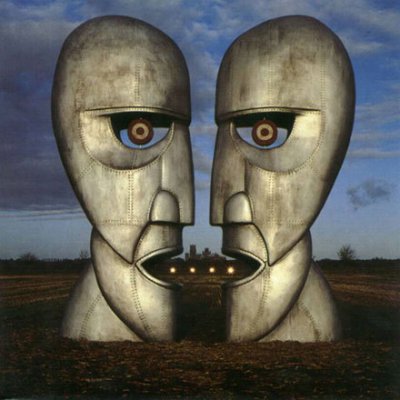

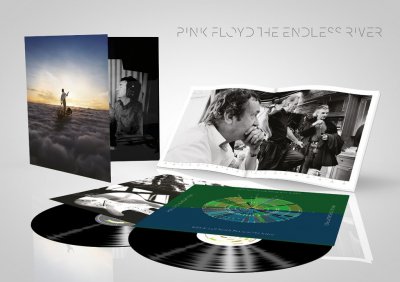

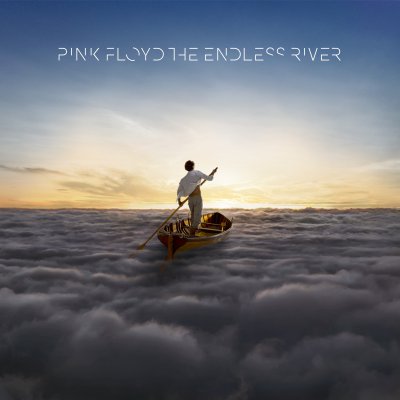

With keyboard player Richard Wright's death in '08 it seemed time was up for Pink Floyd who haven't released an album since The Division Bell 20 years ago. But they offer an elegant farewell on The Endless River (reviewed here), a mostly ambient instrumental album which takes a leisurely pace towards Sum which opens “the second side”, one of the most overtly and archetypal Floyd tracks on it.

And in a world awash with tweets, Facebook postings and leaks, The Endless River – started by co-producer Phil Manzanera in August 2012 – was kept under wraps until Gilmour's wife and lyric writer Polly Samson broke the news on Twitter in July.

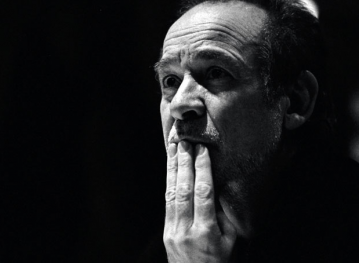

Manzanera – longtime guitarist in Roxy Music, Gilmour's friend since high school and who co-produced the guitarist's On An Island solo album – laughs about how long it took to get just 53 minutes together.

In this age of free streaming of music and pay-what-you-like downloads, a new album by Pink Floyd seems almost quaint.

The Endless River is conceived as four parts, each the length of a side of vinyl, and next week it's being launched in London with a psychedelic light show by Peter Wynne-Willson who did the job at the famous late Sixties club UFO where Floyd played marathon sessions of improvised, tripped-out sounds.

But a new Floyd album is a big deal as he says, and that meant the weight of expectation when he first invited by Gilmour to listen to recordings of the band – Gilmour, Wright and drummer Nick Mason – improvising during The Division Bell sessions, Manzanera went through 20 hours of tapes, and pieced together a musical arc.

I'm given to understand you were

approached to do this music and you decided to listen to every single

outtake from The Division Bell?

I'm given to understand you were

approached to do this music and you decided to listen to every single

outtake from The Division Bell?

Yes, David just said, 'There's this stuff, can you go and have a listen and see if there's anything good there'. When I got the studio on his boat the Astoria there were [engineers] Andy Jackson and Damon Iddins and they said ,'Don't worry, we did this thing called The Big Spliff about 20 years ago, have a listen to that.'

And I said I didn't want to listen to that and that we were going to go back and listen to every single piece of playing they did.

They said, 'You're joking, it's 20 hours and we know it' and I said, 'Well you know it but I've never heard this before' and it took off from there.

A wise man would say, 'Give me the Big Spliff and we'll sort that one out'. So why would you back and listen to everything?

Well it's like empirical sources. When you do research you go back to the original documents so I had taken a leaf out of history research in that regard. I thought there would be things I might like that they wouldn't but I didn't want to skip over them. I don't want to be directed, I wanted to hear everything . . so I know where all the bodies are buried, which is an unfortunate analogy. Sorry about that. Cut that bit out.

I got my notebook out and said, 'Right, let's start at the beginning' and every time something came up that I liked I noted where it was time-wise and then I thought 'What are we doing here? How the hell can we shape this?' My brain was trying to work out this, to make it listenable it needs to be short so I thought 'What's the shortest I could possibly make it' . . two double-sided old fashioned albums.

Classical music has movements which are about 12 minutes long so I thought I could have four 13 minute bits, so we started with side one and put that bit in there and that other bit in there and welded it together much their reticence to start with. In my own mind I constructed a story about what was happening and made up a little narrative.

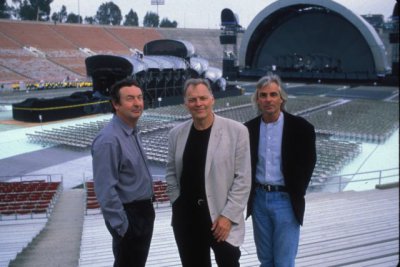

At the end of six weeks I went to David

and said that here it was, four sides long and I gave him my

narrative which I'd written out and done pictures for. He was very

worried about my narrative but could hear some possibilities and said

I should play it to Nick [Mason, right]. So I did and he said there were

possibilities too.

At the end of six weeks I went to David

and said that here it was, four sides long and I gave him my

narrative which I'd written out and done pictures for. He was very

worried about my narrative but could hear some possibilities and said

I should play it to Nick [Mason, right]. So I did and he said there were

possibilities too.

I thought 'Wow this is great' . . . and then nothing happened for nine months. In a typical slow Pink Floyd fashion.

I think David was trying to work out what to do with it, should it even be an album? There were lots of questions in his own mind and then Polly [Samson] his wife – who is his collaborator really, much like Kathleen Brennan is with Tom Waits – had done lyrics for The Division Bell.

She said play it to Youth because David had done this ambient album [Metallic Spheres] with him and he's a big Pink Floyd fan. So he listened to it and loved it and that encouraged David.

David said he liked bits of mine and bits of Youth's ideas so let's get Nick in and work together. So in January this year – and remember when I started it was August 2012 – we were in his studio in Hove near Brighton and then David took control. He could see I'd worked out a method of working and now he was going to insert bits he liked and take out bits he didn't. So he got really involved, as he should.

It became a Pink Floyd project and Nick came down and played drums, and it was only really finished only eight weeks ago because there was so much changing of minds where bits should go, whether something should be shorter or longer. But then there was a deadline.

You thought in terms of four side of old fashioned records, is that because you were mindful that Floyd fans are record buying people. They love records like Dark Side, not the CDs so much.

Yes. Right from the very beginning it was 'What would a Pink Floyd fan like to hear?' Now I'm a Pink Floyd fan from all the different periods, from the Syd period and the Roger period . . .

So I like all the different elements

but I thought, 'This is for the fans. This is not trying to get new

people in'. As it emerged it seemed to be saying goodbye, definitely

saying goodbye as a tribute to Rick. But it looked like it was a slow

cruise into the sunset rather than going out crash-bang-wallop. It

was a sort of chill-out goodbye and very much a hybrid. It was almost

documentary and capturing that moment in time, the last time the

three of them jammed in a way they hadn't done since Wish You Were

Here and the period before that.

So I like all the different elements

but I thought, 'This is for the fans. This is not trying to get new

people in'. As it emerged it seemed to be saying goodbye, definitely

saying goodbye as a tribute to Rick. But it looked like it was a slow

cruise into the sunset rather than going out crash-bang-wallop. It

was a sort of chill-out goodbye and very much a hybrid. It was almost

documentary and capturing that moment in time, the last time the

three of them jammed in a way they hadn't done since Wish You Were

Here and the period before that.

It was the way they would improvise and try to find inspiration in that, and use their own sound colours and their palette of sounds to create something out of nothing.

I was trying to reason . . . because I was very aware of the legacy and the context of things and not wanting to do anything that untoward, given that it wasn't going to be with Roger and that's not going to happen. This is about these three and they provided the musical context for Roger's songs, and even David and Polly's songs when they went out on tour. Their sonority has been brought to the fore on this album.

What it reminds me is that Floyd were always an instrumental group with vocals, but there are huge instrumental passages on all of their albums. I've had the good fortune to have an advance stream and it stuck me as an elegant farewell, maybe for older fans. You send the wife and kids out . . .

[Laughs] And put the headphones on. We like to call it immersive. It's not for everyone, it's a bit like classical music in a way, you've got to sit there and listen to long stretches of music. You can't just listen to a minute of it. It's not classical music, I'm not saying that, but it is in the way you listen to classical music. It is a different experience.

In this day and age everyone does so much around short things to be played on You Tube or Spotify and there's that playlist attitude where you take a track from here and another from there. This is a bit old fashioned in the sense it requires you to sit down, lie down even, and dream away.

It seems there is long gorgeous first side introduction then the old Pink Floyd get to Sum at the start of side two, and that's the archetypal Pink Floyd that a lot of people know and love. There is something more familiar about that.

There were lots of options, you could have had side two as side one. I suggested lots of different options but in the end David went with that version. I had slightly different things in different places but he had to make it his thing, a Pink Floyd album and not a Manzanera version of a Pink Floyd album.

What I was looking for when originally

going through the stuff I loved the Farfisa sound of Rick's right

from the first album. It's called the Duo Compact Farfisa going

through a Binson Echo and I found it. And that's what begins side two

. . and he hadn't used that since Dark Side of the Moon. It's that

keyboard. And I wanted some of that French horn sound he did on

keyboards which he did a lot of on Wish You Were Here.

What I was looking for when originally

going through the stuff I loved the Farfisa sound of Rick's right

from the first album. It's called the Duo Compact Farfisa going

through a Binson Echo and I found it. And that's what begins side two

. . and he hadn't used that since Dark Side of the Moon. It's that

keyboard. And I wanted some of that French horn sound he did on

keyboards which he did a lot of on Wish You Were Here.

I found some of that so started pushing that up, and then I found a bit of jam which reminded me of Echoes or Live at Pompeii and I thought, 'That's great but it doesn't have beat to it'. Then I found some drums where Nick was just warming up and I made a loop out of that and put it underneath the free form bit . . .

Basically I took diabolical liberties just to show David what could be done. I put a bass on it and al sorts of stuff. Well, all my stuff got replaced by David's playing but the idea of it was you could take things and use them, almost using the modern technology and software as an instrument. That's something I have a history of doing with Eno, using the desk and any gear as it was invented to create a further different and interesting sound. You can do that much more easily now with computer software.

Can I put it to you then – and you've mentioned Eno whose work I know, and yours – but David strikes me as the musician guy who knows how to play the beautiful notes but then there is that other level where people like you as producers come in at a different level and as different thinkers who can do something with his work.

What we try and do is give him options and say. 'You could do it this way if you want but you make up your own mind'. Or 'How about this?' Then we do something outrageous and he says, 'No', and I realise I've pushed him to a limit. But that's my function.

He could produce it and do it all himself, but it's boring to do that and it's great to have other people around. There is something about collaborating with people, as they have proved themselves. The sum is bigger than the parts, it adds up to something different. If someone's got a good idea as a musician you take it from whoever said it and say, 'Thanks very much, great idea, I'll have that'.

Can I ask you about a particularly

interesting track, Anisina, the one with saxophone on it. That's a

very straight ahead ballad that almost cries out for lyrics.

Can I ask you about a particularly

interesting track, Anisina, the one with saxophone on it. That's a

very straight ahead ballad that almost cries out for lyrics.

I found a few tracks which sounded like songs without lyrics, one became Louder Than Words and one was Anisina. I always said, 'Please can you write some words for it' and I thought Polly was going to write for both, but once she'd written Louder Than Words and the concept of it then she decided there were no words needed.

And if you stick [Louder Than Words] at the end it's not only a comment on the album, but looking back on their working relationship. Conceptually it was better to just have that one thing [with lyrics].

Consequently Anisina needed something extra to it and so the saxophone came in, as a lament for Rick really.

Who plays sax?

It's a friend of mine Gilad Atzmon who's played on some of my things and with Robert Wyatt. He's an Israeli saxophonist and a genius. People will know his playing because of Ian Dury's Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick.

You mentioned Robert Wyatt and I see he's announced he's officially retired. No more from Robert?

[Laughs] We all say this kind of thing but in fact he's coming here in two weeks time to put a little bit of trumpet and vocals on a Latin American project I'm doing. I think that's just to take the pressure off him in having to do another album.

I think David Bowie retired about three times in the Seventies.

[Laughs] It's the oldest trick in the book and I said something to Rolling Stone in America a few weeks ago about this project and it came out yesterday as a Google Alert that Roxy had now split. Fine. But ultimately with all these things if you met up with one of your band mates tomorrow and said, 'Let's just go and do it' and people would say, 'But you split?'

Well, we changed our mind. Of course if someone passes away as with Rick then that's different. Even if Roger was involved in this you've not got those four people together. But if you are in bands when you get to a certain age you just want to not have the encumbrance of other people telling you what to do.

Which brings us the next question, do you think the Beatles will ever get back together?

[Laughs]

I understand what you mean, people should be entitled to just do what they do.

That's that's great thing about being a musician, there are no rules. When you became a musician in the Sixties or Seventies you weren't controlled by the corporate people, you just bumbled along doing whatever you fancied. If you made some money, fine. If you didn't that was fine too but you just kept doing it, because you loved it. We're all of a certain age and are still doing that, we have no career path.

It's a bit late to get one now though. Life worked out really, didn't it? Can I ask you this, when you were looking at this project you would have been very aware of the legacy of Pink Floyd and knowing this was going to be the final statement . . .

David has said it pretty much is.

There would be the weight of expectation but also perhaps a sense of relief for David. How did you read that?

I would have thought there would have been a sense of relief. David's said, 'This is the bookend album and we're going out in a chilled-out way, but if you want songs I'm doing my new solo album then you'll get plenty of them next year.'

That weight of expectation . . . Floyd fans are waiting for this.

It is a big deal, it's a big deal here and I've been told it has broken the record for the most advance sales on Amazon . . . even beating One Direction! And Coldplay, all the big guns. What that means I've got no idea, but it's the name.

We know bands which came up in the last 40 years have become brand names, whether it's Blur, Oasis, Pink Floyd, Roxy Music, the Rolling Stones . . . they acquire something above their individual members. It's like a state of mind; the Floyd album, the Floyd fan, a Floyd show . . it's not just about the music. There's a visual things too.

Next week we are having the most

fantastic launch here with the guy who did the original psychedelic

light show at the UFO Club [where Pink Floyd played in the late

Sixties], Peter Wynne-Willson doing a live psychedelic show in the

whole huge room. And they will film some of it. It's so exciting and

totally unique, that will be so much fun. We're all going to be there

and there will be bean bags. . .

Next week we are having the most

fantastic launch here with the guy who did the original psychedelic

light show at the UFO Club [where Pink Floyd played in the late

Sixties], Peter Wynne-Willson doing a live psychedelic show in the

whole huge room. And they will film some of it. It's so exciting and

totally unique, that will be so much fun. We're all going to be there

and there will be bean bags. . .

No one is actually going to play though? It's just going to be an event?

They will play the whole album with the light show so people will be totally immersed in this for 55 minutes. It's going to be a real, dare I say it, happening. No live musicians, but they will be walking around.

I remember when George Harrison came to New Zealand someone asked him why he didn't appear live and he said, 'Well, I'm live right now.' Can I ask about your own album The Sound of Blue. What's the status of that?

Cheekily I've just done a bonus track

for it. I've done a version of a thing called No Church in the Wild

which was a track Jay-Z and Kanye West did for the album Watch the

Throne which used a sample of my guitar from my K-Scope album. They

sampled and slowed it down and that riff goes through the whole song.

It won a Grammy and been incredibly successful.

Cheekily I've just done a bonus track

for it. I've done a version of a thing called No Church in the Wild

which was a track Jay-Z and Kanye West did for the album Watch the

Throne which used a sample of my guitar from my K-Scope album. They

sampled and slowed it down and that riff goes through the whole song.

It won a Grammy and been incredibly successful.

I'd finished my mainly instrumental album Sound of Blue and then I thought 'Wouldn't it be a laugh if I did a version of their version'. So I've got this Portuguese girl singing on it and it's turned out really great. It is going to come out next, year in January, February or March. And I'll be doing a bit of playing with my little band. So there's that and Corroncho which is the all-Spanish album which I do with my Columbian friend Lucho Brieva.

So aside from the Floyd thing you've got another job to do, which is your own life.

[Laughs] Yes. It's funny that everyone in Roxy is still out there. Bryan [Ferry] has got a new album coming out next week, Eno's just brought out one with Karl from Underworld, Andy Mackay comes here once a week because he's working on an album in my studio, I'm putting out my stuff . . . We're all in the game, we refuse to be put town.

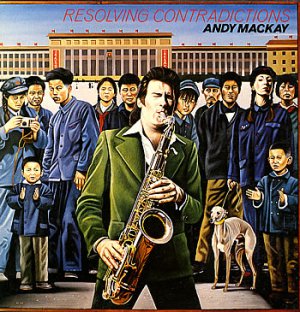

I can tell you without a word of lie

that I have Andy's cover for Resolving Contradictions framed on my

wall.

I can tell you without a word of lie

that I have Andy's cover for Resolving Contradictions framed on my

wall.

Oh I must tell him, he'll like that.

I'm now on limited time here Phil, but the great unspoken is Roger Waters. Has Roger made any comment on this Floyd album?

As far as I know he hasn't except to say he's not involved. I read a thing where he was quite sensibly saying he left about 30 years ago and is happy doing his own stuff. David said something the other day, 'I was 30 when Roger left, I'm 68 now'. [Not quite true.]

We forget that space of time.

It is the most peculiar thing that the legacy of Pink Floyd is so enormous. I'm sure you've done interviews where people have asked you about Syd Barrett.

Yes. But it wouldn't have been correct

for Roger to have been involved in this one because he'd left years

before and wasn't there when they did this jamming, and it's all

based around the jamming.

Yes. But it wouldn't have been correct

for Roger to have been involved in this one because he'd left years

before and wasn't there when they did this jamming, and it's all

based around the jamming.

There is some beautiful stuff on there. On Noodle Street is a lovely ambient piece.

It is. I hope Floyd fans will like this, it is done for them.

One for old fans, 'Thank you so much and goodbye'?

Yes, and it is a nice fitting tribute to Rick and it's coming from a good place.

One last comment. I really don't like the album cover, it's not "Pink Floyd" to me.

[Laughs] I'm not responsible for that. I'm just responsible for some of the music. I can talk to you about some of the Roxy Music album covers which I love . . . but that's all I'll say.

Ever the diplomat, Phil.

post a comment