Graham Reid | | 6 min read

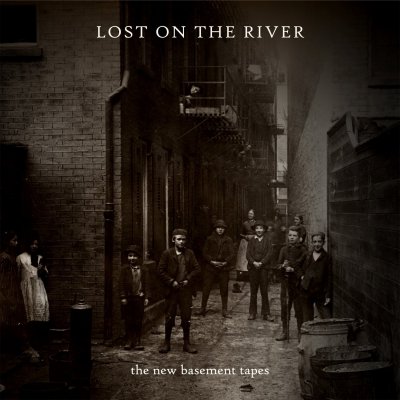

Rhiannon Giddens: Spanish Mary

Oddly enough Burnett, who counts Dylan a longtime close friend and has worked with him on a number of occasions, admits he hasn't heard all of the original Basement Tapes, those legendary sessions between Dylan and what would become The Band recorded in sprawling, free-flowing sessions at Woodstock in upstate New York from mid '66.

But Burnett had his mind elsewhere, even though a bit buried in Bob.

He got a call from Dylan's publisher in 2011 saying Dylan had discovered a box of lyrics from '67 which were never set to song and would he like to do something with them.

So Burnett assembled his crew: Elvis Costello, Jim James from My Morning Jacket, Marcus Mumford of Mumford and Sons, Taylor Goldsmith from Dawes and Rhiannon Giddens from Carolina Chocolate Drops.

These were all people he felt could bring something unique to the project, and he laughs when I suggest the old phrase favoured by schoolteachers, that they would “play well with others”.

He says that "98 percent" of the lyrics on the album are Dylan's originals -- Costello added some verses in places -- and that in a couple of instances the artists needed to create choruses from the words on the page, some of which were handwritten and other typed.

The result is an album of 15 very diverse songs – 20 in the expanded edition – which includes the haunting Spanish Mary (sung by Giddens) two versions of the title track, the rollicking nonsense of Married to My Hack (by Costello) and a lovely piano ballad by Goldsmith entitled Liberty Street which sounds close to classic James Taylor.

In fact although the author was Bob Dylan there are only a few times when that character seems to impose himself. As Burnett notes: “It became irrelevant at some point once we got into it that it was Bob who had written them.”

You've got this very interesting

group of people together, you've known Elvis Costello for a very long

time and Jim James too. How long had you known Marcus Mumford prior

to this?

You've got this very interesting

group of people together, you've known Elvis Costello for a very long

time and Jim James too. How long had you known Marcus Mumford prior

to this?

I've known Marcus for a few years, we worked on [the film/soundtrack] Inside Llewyn Davis and we'd met a few years ago when he, Dylan and the Avett Brothers did a performance at the Grammy's that I worked on. We met then.

What could he in particular bring to a project like this?

What all these guys bring are themselves, they are extraordinarily generous, talented, kind, smart people. So he what he brought more than anything else was his soul, his tone. The way he is. He is deeply kind.

I don't want to couch this the wrong way, but did you feel you needed a woman's voice in there or was Rhiannon just another of those people you immediately thought about because she has a gift for this kind of thing.

I was working with Rhiannon at the time so it came up naturally but I'm also happy to say we do have a woman in there. We didn't call her because she was a woman of course, but certainly that was a plus

I think her song Spanish Mary is an outstanding piece on the album.

I do too, a very beautiful piece, and timeless. It sounds like it could have been written 300 years.

And then you get something else which is very frivolous like Nothing To It?

Yeah exactly.

Are there any favourites you have because they shaped up in a way you didn't anticipate.

Not really, they were all so unexpected, so I don't really have any favourites . . . although if I think about the album I like some of the quieter ones like Golden Tom- Silver Judas is a beautiful piece, I like the last Lost on the River that Rhiannon did. But I like all the stuff and wouldn't want to short anybody out.

Was it necessary for the artists to put aside the authorial hand and just look at them as lyrics they needed to shape, regardless of who had written them.? Not think, 'What would Bob Dylan would do?' It was important to put Dylan out of the picture at some point.

Yeah, I think that was the idea. He just said, 'Have at it ' so the idea was just to take the lyrics for what they were worth and see where they lead. So it became irrelevant at some point once we got into it that it was Bob who had written them.

You could easily fall into adopting a familiar chord progression from Blonde and Blonde or the Basement Tapes.

Right, that would have been heavy-handed and everybody would have made fun of us. [Laughs]

I'll use the analogy from the movie industry, you are more like a benign producer than a hands-on director in these matters. You let people go?

I try to have as light a touch as possible, especially when you are working with people like this where everyone is so good. All you want to do is encourage them to bring their best. None of these people needed direction and they all had their own vision to follow. That last thing I wanted to do was either get in the way of somebody's vision or cause somebody to stop being creative.

Some of the artists came in with some of the music already done I believe. Did you send out all the lyrics to everyone in advance.

I did. I sent the 16 lyrics to everyone. Some people got busy and wrote songs with them and some people didn't and just thought they'd wait until they got to the studio and see what they could cook up together. And then as we were going in eight new songs showed up, so that was a whole other time of improvisation really.

The people who came in with music written – I believe Costello and Jim James were among them – were they happy to let them go if others felt they could go another direction? Or were those ones mostly realised in the studio the way they brought them in.

I don't think anybody brought anything in with absolute definite idea of how it would go, maybe Jim most of all because he'd recorded some things with other instruments. But early on when it became clear that we had so many versions we just decided to record everything. That's how we started working. It was incredibly fast. We recorded 45 songs in 12 days.

So there's a New Basement Tapes box set on its way?

[Laughs] At some point I'd love to go in and finish up some of the things we didn't get to, there are some beautiful things there. But the idea was not to place one person's version over another persons. We did four versions of Lost on the River. Marcus and Rhiannon on that beautiful one that ends it, Jim James has written an incredible one and Taylor wrote one too. Hopefully we'll get to those songs further down the road. Taylor was so careful in his writing, he would write a note for every syllable on the page, just beautiful.

Was it because that song just appealed to everybody in a different way and they saw something in it they could bring to it.

Yeah, it was probably the most complete one, and the most identifiable as a type of song. Even though everybody drew completely different types of songs from it. Not one of the songs sounds like any of the other versions.

That's a testament to the strength

of the lyrics.

That's a testament to the strength

of the lyrics.

I think it is. and one of the things that interested me the most about the project was all the different versions which would emerge, and where they would converge and where they would be completely different.

Occasionally a verse would be so evocative of a certain type of song, the cadence would be so clear for instance, that it would suggest a very specific melody. So that would happen a few times.

I've only heard the shorter version of the album, I understand there is another with some extra material.

The 20-song record is really worth it. It's got four songs from each of these extraordinary artists. The shorter one tells a story but the longer version tells a better one.

I understand that Bob was in a nearby studio recording his standards album, did he ever stick his head in the studio and give a nod or a shake of the head?

He was around the whole time but he wasn't in the studio. He really did just throw it at us and say 'Have at it'. He didn't want to inhibit anything.

That is a remarkable thing, that entails an enormous amount of trust if nothing else.

It does, and a generosity. It is very generous to throw your work open to a group of people who are some younger and some older. It's a beautiful gift from Bob.

I know you've been asked this already but I've seen slight variations in your answer, has there been any comment from Dylan to you directly.

No. [Laughs] I haven't spoken to him since we started this. In fact I made a point of not seeing him when he was there. I don't know why, it was just the way I wanted to do it.

I won't speak for Bob. But the temptation is to say, 'Yeah, Bob heard this and called to say he thinks it's the best thing he's ever done!'

"And that's a joke."

.

post a comment